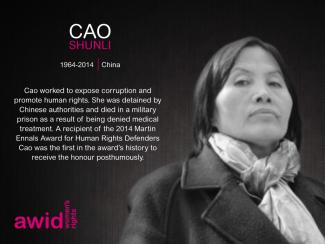

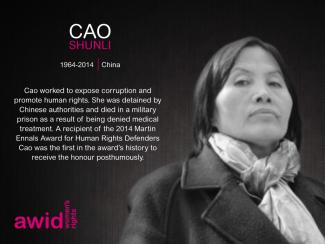

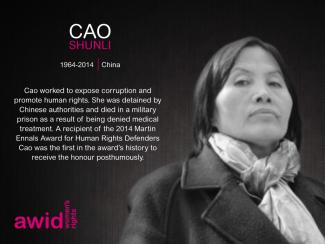

Cao Shunli

Across the globe, feminist, women’s rights and gender justice defenders are challenging the agendas of fascist and fundamentalist actors. These oppressive forces target women, persons who are non-conforming in their gender identity, expression and/or sexual orientation, and other oppressed communities.

Discriminatory ideologies are undermining and co-opting our human rights systems and standards, with the aim of making rights the preserve of only certain groups. In the face of this, the Advancing Universal Rights and Justice (AURJ) initiative promotes the universality of rights - the foundational principle that human rights belong to everyone, no matter who they are, without exception.

We create space for feminist, women’s rights and gender justice movements and allies to recognize, strategize and take collective action to counter the influence and impact of anti-rights actors. We also seek to advance women’s rights and feminist frameworks, norms and proposals, and to protect and promote the universality of rights.

Our 2009 Annual Report includes highlights of another busy year of action and reflection at AWID as we implement our commitment to boldly, creatively and effectively contribute to the advancement of women’s rights and gender equality worldwide.

In the report you can find out about our programmatic achievements, membership, finances, what to watch out for in 2010, as well as information about our Board and Staff.

Marianne Mesfin Asfaw is a Pan-African feminist who is dedicated to social justice and building community. She has a BA in Gender Studies and International Relations from the University of British Columbia (UBC), and an MA in Gender Studies and Law from SOAS University of London. She has previously worked in academic administration and international student support, and has worked as a researcher and facilitator in feminist and non-profit spaces. She has also worked and volunteered at non-governmental organizations including Plan International in administrative roles. Prior to taking up her current role she worked in logistics and administrative support at AWID. She is from Ethiopia, was raised in Rwanda and is currently based in Tkaronto/Toronto, Canada. She enjoys reading, traveling and spending time with her family and friends. In the warmer months she can be found strolling around familiar neighborhoods in search of obscure cafés and bookstores to wander into.

Veena Singh is a Fiji Islander, feminist, and woman of colour. Born and raised in a small rural town in Fiji, she draws strength from her rich mixed heritage (her mother is an Indigenous Fijian woman and her father is Fijian of Indian descent). Veena’s identity and lived experiences deeply inform her commitment to justice, equity, and inclusion. With over two decades of experience in human rights, gender equality, community development, and social inclusion, Veena is a passionate advocate for shifting power to create transformative change and for building an “economy of kindness”. Her work spans diverse areas including community development; women, peace and security; social policy; human rights; and policy advocacy.

Veena is deeply committed to advancing inclusion, peace and justice, sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), climate justice, transitional justice, and human rights. She brings a wealth of experience working across grassroots networks, international organizations, and government institutions, always centering community and locally led approaches and feminist principles.

Outside of her ‘office life’, Veena is an environmental advocate, mental health champion, and writer. She is a mum to 11 cats, a saree wearer, and a lover of snail-mails and postcards. A thoughtful observer of feminist movements in Fiji and the Pacific, Veena is on a personal journey to “decolonise the mind and the self through radical self-reflection.” Above all, she is driven by a desire and dream to produce relatable, resonant writing that connects with the Pacific diaspora and amplifies voices from the margins.

Alejandra is passionate about women’s rights and gender justice. She dreams of creating a world that centers care – for people and nature. As a feminist human rights expert, she’s worked at the intersections of gender, climate, social and economic justice at various international organizations. Her areas of expertise include knowledge building and co-creation, research, facilitation, and advocacy. She holds a MA in Human Rights from the University of Essex and has authored and co-developed many publications, including the article “Enraged: Women and Nature”. The campaign Feminist Activism Without Fear draws on interviews and research carried out by Alejandra.

Originally from Argentina, she has lived and worked in several countries in Europe and Latin America over the past two decades. Alejandra loves photography, the sea, baking with her daughter, and enjoying food from around the world. As a mother, she aims to be a cycle breaker. Alejandra draws energy and inspiration from the amazing women in her life, who are spread in many corners of the world.

The 1st drafting session on the outcome document for the 3rd Financing for Development Conference

This information will only be available when registration opens.

|

Human and ethnic-territorial rights Ensuring the defense of human rights and Nature’s rights through alliance-building with local, national, regional and global actors and organizations. |

|

Sustainable development Ensuring all economic, cultural and environmental activities contribute to sustainable development, food security and income generation, while respecting the self-determination and self-government of Afro-descendant communities. |

|

Education and training Carrying out training for women and empowering them to carry out women’s rights advocacy in different political, social and economic spaces. For more information, see here! |