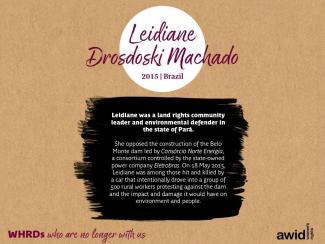

Leidiane Drosdoski Machado

Across the globe, feminist, women’s rights and gender justice defenders are challenging the agendas of fascist and fundamentalist actors. These oppressive forces target women, persons who are non-conforming in their gender identity, expression and/or sexual orientation, and other oppressed communities.

Discriminatory ideologies are undermining and co-opting our human rights systems and standards, with the aim of making rights the preserve of only certain groups. In the face of this, the Advancing Universal Rights and Justice (AURJ) initiative promotes the universality of rights - the foundational principle that human rights belong to everyone, no matter who they are, without exception.

We create space for feminist, women’s rights and gender justice movements and allies to recognize, strategize and take collective action to counter the influence and impact of anti-rights actors. We also seek to advance women’s rights and feminist frameworks, norms and proposals, and to protect and promote the universality of rights.

|

Tshegofatso Senne is a Black, chronically-ill, genderqueer feminist who does the most. Much of their work is rooted in pleasure, community, and dreaming, while being informed by somatic abolitionism and disability, healing, and transformative justices. Writing, researching, and speaking on issues concerning feminism, community, sexual and reproductive justice, consent, rape culture, and justice, Tshegofatso has 8 years of experience theorising on the ways in which these topics intersect with pleasure. They run their own business, Thembekile Stationery, and their community platform Hedone brings people together to explore and understand the power of trauma-awareness and pleasure in their daily lives. Tshegofatso believes deeply in the individual and collective potential of regenerative and sustainable change, pleasure, and care work. |

The body, not the thinking brain, is where we experience most of our pain, pleasure, and joy, and where we process most of what happens to us. It is also where we do most of our healing, including our emotional and psychological healing. And it is where we experience resilience and a sense of flow.

These words, said by Resmaa Menakem in his book My Grandmother’s Hands, have stayed with me.

The body; it holds our experiences. Our memories. Our resilience. And as Menakem has written, the body also holds our traumas. It responds with spontaneous protective mechanisms to stop or prevent more damage. That is the power of the body. Trauma is not the event; it is how our bodies respond to events that feel dangerous to us. It is often left stuck in the body, until we address it. There’s no talking our body out of this response – it just is.

Using Ling Tan’s Digital Superpower app, I tracked how my body felt as I travelled around different parts of my city, Johannesburg, South Africa. The app is a gesture-driven online platform that allows you to trace your perceptions as you move through locations by logging and recording the data. I used it to track my psychosomatic symptoms – physical reactions connected to a mental cause. Whether that be flashbacks. Panic attacks. Tightness in the chest. A fast heartbeat. Tension headaches. Muscle pain. Insomnia. Struggling to breathe. I tracked these symptoms as I walked and travelled to different areas in Johannesburg. And I asked myself.

Where can we be safe? Can we be safe?

Psychosomatic responses can be caused by a number of things, and some are not as severe as others. After experiencing any kind of trauma you may feel intense distress in similar events or situations. I tracked my sensations, ranked on a scale of 1-5, where 1 were the instances I barely felt any of these symptoms – I felt at ease rather than on-guard and jumpy, my breath and heart rate were stable, I was not looking over my shoulder – and number 5 being the opposite – symptoms that had me close to a panic attack.

As a Black person. As a queer person. As a genderqueer person who could be perceived as a woman, depending on what my gender expression is that day.

I asked myself.

Where can we be safe?

Even in neighbourhoods one might consider “safe,” I felt constantly panicked. Looking around me to make sure I wasn’t being followed, adjusting the way my T-shirt sat so my breasts wouldn’t show up as much, looking around to make sure I knew multiple routes to get out of the place I was should I sense danger. An empty road brings anxiety. A packed one does too. Being in an Uber does. Walking on a public road does. Being in my apartment does. So does picking up a delivery from the front of the building.

Can we be safe?

Pumla Dineo Gqola speaks of the Female Fear Factory. It may or may not be familiar, but if you’re someone socialised as a woman, you’ll know this feeling well. The feeling that has you planning every step you take, whether you’re going to work, school, or just running an errand. The feeling that you have to watch how you dress, act, speak in public and private spaces. The feeling in the pit of your stomach if you have to travel at night, get a delivery, or deal with any person who continues to socialise as a cis man. Harassed on the street, always with the threat of violence. Us existing in any space comes with an innate fear.

Fear is both an individual and a socio-political phenomenon. At an individual level, fear can be present as part of a healthy well developing warning system […] When we think about fear, it is important to hold both notions of individual emotional experience and the political ways in which fear has been used in different epochs for control.

- Pumla Dineo Gqola, in her book Rape: A South African Nightmare

South African women, femmes, and queers know that every step we take outside – steps to do ordinary things: a walk to the shops, a taxi to work, an Uber from a party – all of these acts are a negotiation with violence. This fear, is part of the trauma. To cope with the trauma we carry in our bodies, we develop responses to detect danger – watching the emotional responses of those around us, reading for “friendliness.” We’re constantly on guard.

Day after day. Year after year. Life after life. Generation after generation.

On the additional challenge of this learned defence system, author of The Body Keeps Score, Bessel Van Der Kolk, has said

It disrupts this ability to accurately read others, rendering the trauma survivor either less able to detect danger or more likely to misperceive danger where there is none. It takes tremendous energy to keep functioning while carrying the memory of terror, and the shame of utter weakness and vulnerability.

As Resmaa Menakem has said, trauma is in everything; it infiltrates the air we breathe, the water we drink, the foods we eat. It is in the systems that govern us, the institutions that teach and also traumatise us, and within the social contracts we enter into with each other. Most importantly, we take it with us everywhere we go, in our bodies, exhausting us and eroding our health and happiness. We carry that truth in our bodies. Generations of us have.

So, as I walk around my city, whether an area is considered “safe” or not, I carry the traumas of generations whose responses are embedded in my body. My heart palpitates, it becomes difficult to breathe, my chest tightens – because my body feels as though the trauma is happening in that very moment. I live hyper vigilant. To the point where one is either too on-guard to mindfully enjoy their life, or too numb to absorb new experiences.

For us to begin to heal, we need to acknowledge these truths.

These truths that live in our bodies.

This trauma is what keeps many of us from living the lives we want. Ask any femme or queer person what safety looks like to them and they’ll mostly share examples that are simple tasks – being able to simply live joyful lives, without the constant threat of violence.

Feelings of safety, of comfort and ease, are spatial. When we embody our trauma, it affects the ways we perceive our own safety, affects the ways we interact with the world, and alters the ways we are able to experience and embody anything pleasurable and joyful.

We have to refuse this burdensome responsibility and fight for a safe world for all of us. Walking wounded as many of us are, we are fighters. Patriarchy may terrorise and brutalise us, but we will not give up the fight. As we repeatedly take to the streets, defying the fear in spectacular and seemingly insignificant ways, we defend ourselves and speak in our own name.

- Pumla Dineo Gqola, in her book Rape: A South African Nightmare

Where can we be safe? How do we begin to defend ourselves, not just in the physical sense, but in the emotional, psychological, and spiritual senses?

“Trauma makes weapons out of us all,” adrienne maree brown has said in an interview conducted by Justin Scott Campbell. And her work, Pleasure Activism, offers us multiple methodologies to heal that trauma and ground ourselves in the understanding that healing, justice, and liberation can also be pleasurable experiences. Especially those of us who are the most marginalised, who may have been raised to equate suffering with “The Work.” The Work that so many of us have gone into as activists, community builders and workers, those serving the most marginalised, The Work that we struggle in order to do, burning ourselves out and rarely caring for our minds and bodies. The alternative is becoming more informed about our trauma, able to identify our own needs, and becoming deeply embodied. That embodiment means we are simply more able to experience the world through the senses and sensations in our bodies, acknowledging what they tell us rather than suppressing and ignoring the information it is communicating with us.

Being constantly in conversation with our living body and intentionally practising those conversations connects us to embodiment more deeply; it allows us to make tangible the emotions we feel as we interact with the world, befriend our bodies, and understand all that they try to teach us. When understanding trauma and embodiment paired, we can begin to start the healing and access pleasure more holistically, healthily, and in our daily lives without shame and guilt. We can begin to access pleasure as a tool for individual and social change, tapping into the power of the erotic as Audre Lorde described it. A power that allows us to share the joy we access and experience, expanding our capacity for happiness and understanding that we are deserving of it, even with our trauma.

Tapping into pleasure and embodying the erotic gives us the expansion of being deliberately alive, feeling grounded and stable and understanding our nervous systems. It allows us to understand and shed the generational baggage we’ve been carrying without realising; we can be empowered with the knowledge that even as traumatised as we are, as traumatised as we potentially could be in the future, we are still deserving of pleasurable and joyful lives, that we can share that power with our people. It is the community aspect that is missing from the ways we care for ourselves; self-care cannot exist without community care. We are able to feel a deeper internal trust, safety, and power of ourselves, especially in the face of future traumas that will trigger us, knowing how to soothe and stabilise ourselves. All this understanding leads us to a deep internal power that is resourced to meet any challenges that come your way.

As those living with deep generational traumas, we have come to distrust and perhaps think we are incapable of containing and accessing the power we have. In “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Lorde teaches us that the erotic offers a source of replenishment, a way to demand better for ourselves and our lives.

For the erotic is not a question only of what we do; it is a question of how acutely and fully we can feel in the doing. Once we know the extent to which we are capable of feeling that sense of satisfaction and completion, we can then observe which of our various life endeavours brings us closest to that fullness.

I don’t say any of this lightly – I know that this is easier said than done. I know that many of us are prevented from understanding these truths, from internalising or even healing them. Resistance comes with acts of feeling unsafe, but is not impossible. Resisting power structures that keep the most powerful safe will always endanger those of us shoved to the margins. Acknowledging the traumas you’ve faced is a reclamation of your lived experiences, those that have passed and those that will follow; it is resistance that embodies that knowledge that we are deserving of more than the breadcrumbs these systems have forced us to lap up. It is a resistance that understands that pleasure is complicated by trauma, but it can be accessed in arbitrary and powerful ways. It is a resistance that acknowledges that our trauma is a resource that connects us to each other, and can allow us to keep each other safe. It is a resistance that understands that even with pleasure and joy, this is not a utopia; we will still harm and be harmed, but we will be better equipped for survival and thrive in a community of diverse care and kindness. A resistance that makes way for healing and connecting to our full human selves.

Healing will never be an easy and rosy journey, but it begins with the acknowledgment of the possibility. When oppression makes us believe that pleasure is not something that we all have equal access to, one of the ways that we start doing the work of reclaiming our full selves — our whole liberated, free selves — is by reclaiming our access to pleasure.

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha has said in her article in Pleasure Activism (to which she contributed),

I know that for most people, the words “care” and “pleasure” can’t even be in the same sentence. We’re all soaking in ableism’s hatred of bodies that have needs, and we’re given a really shitty choice: either have no needs and get to have autonomy, dignity, and control over your life or admit you need care and lose all of the above.

The power that this has? We understand our traumas, so we understand those of others; we embody the sensations we experience and tend to them rather than distract and avoid. We access pleasure in ways that make us want to share that joy with those in our communities. When we are trauma-informed, we give ourselves more room to experience all this and give ourselves, and others, permission to heal. Imagine, a community in which everyone has access, resources, and time to live pleasurable lives, in whichever way they want and deserve. In which spatial traumas are lessened because the people that occupy them are trauma-aware, are filled with a tender care. Isn’t that healing? Is that not working through generational traumas? Does that not build and sustain healthier futures for us all?

It is time we reconnected with the ancestral knowledge that we deserve to live full lives. We need to get back in touch with our natural right to joy and existing for ourselves. To feel pleasure simply for the sake of it. To not live lives of terror. It sounds radical; it feels radical. In a world where we have been socialised and traumatised to numb, to fear, to feel and remain powerless, to be greedy and live with structural issues that lead to mental illness, what a gift and wonder it is to begin to feel, to be in community with those who feel, to be healthily interdependent in, to love each other boldly. Feeling is radical. Pleasure is radical. Healing is radical.

You have permission to feel pleasure. You have permission to dance, create, make love to yourself and others, celebrate and cultivate joy. You are encouraged to do so. You have permission to heal. Don’t bottle it up inside, don’t try to move through this time alone. You have permission to grieve. And you have permission to live.

- adrienne maree brown, “You Have Permission”

Somatic embodiment allows us to explore our trauma, work through it and make meaningful connections to ourselves and the collective. Doing this over time sustains our healing; just like trauma, healing is not a one-time only event. This healing helps move us toward individual and collective liberation.

In “A Queer Politics of Pleasure,” Andy Johnson speaks about the ways in which the queering of pleasure offers us sources of healing, acceptance, release, playfulness, wholeness, defiance, subversion, and freedom. How expansive! When we embody pleasure in ways that are this holistic, this queer, we are able to acknowledge the limitation.

Queering pleasure also asks us the questions that intersect our dreaming with our lived realities.

Who is free or deemed worthy enough to feel pleasure? When is one allowed to feel pleasure or pleased? With whom can one experience pleasure? What kind of pleasure is accessible? What limits one from accessing their full erotic and pleased potential?

- Andy Johnson, “A Queer Politics

of Pleasure”

When our trauma-informed pleasure practices are grounded in community care, we begin to answer some of these questions. We begin to understand the liberating potential. As pleasure activists, this is the reality we ground ourselves within. The reality that says, my pleasure may be fractal, but it has the potential to heal not only me and my community, but future bloodlines.

I am a whole system; we are whole systems. We are not just our pains, not just our fears, and not just our thoughts. We are entire systems wired for pleasure, and we can learn how to say yes from the inside out.

- Prentis Hemphill, interviewed by Shar Jossell

There’s a world of pleasure that allows us to begin to understand ourselves holistically, in ways that give us room to rebuild the realities that affirm that we are capable and deserving of daily pleasure. BDSM, one of my deepest pleasures, allows me a glimpse into these realities where I can both feel and heal my trauma, as well as feel immeasurable opportunities to say yes from the inside out. While trauma keeps me stuck in a cycle of fight or flight, bondage, kneeling, impact, and breath play encourage me to stay grounded and connected, reconnecting to restoration. Pleasure that is playful allows me to heal, to identify where traumatic energy is stored in my body and focus my energy there. It allows me to express the sensations my body feels through screams of pain and delight, to express my no with no fear and revel in the fuck yes. With a safety plan, aftercare, and a deeper understanding of trauma, kink offers a place of pleasure and healing that is invaluable.

So whether your pleasure looks like cooking a meal at your leisure, engaging in sex, having bed days with your people, participating in disability care collectives, having someone spit in your mouth, going on accessible outings, having cuddle dates, attending an online dance party, spending time in your garden, being choked out in a dungeon,

I hope you take pleasure with you wherever you go. I hope it heals you and your people.

Recognising the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world.

- Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power”

This journal edition in partnership with Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, will explore feminist solutions, proposals and realities for transforming our current world, our bodies and our sexualities.

نصدر النسخة هذه من المجلة بالشراكة مع «كحل: مجلة لأبحاث الجسد والجندر»، وسنستكشف عبرها الحلول والاقتراحات وأنواع الواقع النسوية لتغيير عالمنا الحالي وكذلك أجسادنا وجنسانياتنا.

By: Marianne Mesfin Asfaw

I have many fond memories in my journey with feminism, but one in particular that stands out. It was during my time at graduate school, at a lecture I attended as part of a Feminist Theory course. This lecture was on African feminism and in it the professor talked about the history of Pan Africanism and the ways in which it was patriarchal, male-centric, and how Pan Africanist scholars perpetuated the erasure of African women. She talked about how African women’s contributions to the anti-colonial and decolonial struggles on the continent are rarely, if ever, discussed and given their due credit. We read about the African feminist scholars challenging this erasure and actively unearthing these stories of African women led movements and resistance efforts. It seems so simple but what stood out to me the most was that somebody put the words African and feminist together. Better yet, that there were many more of us out there wrestling with the complicated history, politics and societal norms in the various corners of the continent and we were all using a feminist lens to do this. I came out of that lecture feeling moved and completely mind-blown. After the lecture three of my friends (all African feminists) and I spent some time debriefing outside the classroom. We were all so struck by the brilliance of the lecture and the content but, more than anything, we all felt so seen. That feeling stood out to me.

Falling in love feminism was thrilling. It felt like finally getting to talk to your longtime crush and finding out that they like you back. I call it my crush because in high school I referred to myself as a feminist but I didn’t feel like I knew enough about it. Was there a right way to be feminist? What if I wasn’t doing it right? Attending my first Women’s Studies lecture answered some of these questions for me. It was thrilling to learn about stories of feminist resistance and dismantling the patriarchy. I felt so affirmed and validated, but I also felt like something was missing.

Deepening my relationship with feminism through academia, at an institution where the students and teaching staff were mostly white meant that, for those first few years, I noticed that we rarely had discussions about how race and anti-blackness show up in mainstream feminist movements. In most courses we had maybe 1 week, or worse 1 lecture, dedicated to race and we would usually read something by bell hooks, Kimberly Crenshaw’s work on intersectionality, and maybe Patricia Hill Collins. The following week we were back to sidelining the topic. I dealt with this by centring race and black feminism in almost all my assignments, by writing about black hair and respectability politics, the hypersexualization of black women’s bodies, and so much more. Over time I realized that I was trying to fill a gap but didn’t quite know what it was.

Encountering and learning about African feminism was a full circle moment. I realized that there was so much more I had to learn.

Mainly that my Africanness and my feminist politics did not have to be separate. In fact, there was so much that they could learn from each other and there were African feminists out there already doing this work. It was the missing piece that felt so elusive during my exploration of feminism throughout my academic journey.

Feminism to me is the antithesis to social and political apathy. It also means once you adopt a feminist lens, nothing can ever be the same. My friends and I used to talk about how it was like putting on glasses that you can never take off because you now see the world for what it is, mess and all. A mess you can’t simply ignore or walk away from. Therefore my vow to the feminist movement is to never stop learning, to keep stretching the bounds of my empathy and to never live passively. To dedicate more time and space in my life to feminist movements and to continue to amplify, celebrate, document and cite the work of African feminists. I also commit to centring care and prioritizing pleasure in this feminist journey because we can’t sustain our movements without this.

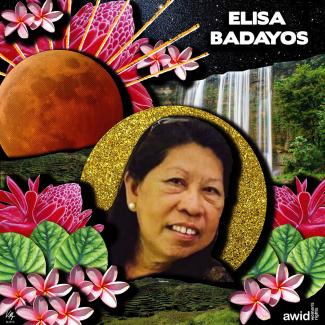

She also served as an organiser of urban poor communities in Cebu Province, and worked with Desaparecidos, an organization of families of the disappeared.

Elisa and two of her colleagues were killed on November 28, 2017 by two unidentified men at Barangay San Ramon, Bayawan city in the Negros Oriental province during a mission to investigate alleged land rights abuses in the area.

She is survived by four children.

ประเด็นหลักของเวที – ลุกขึ้นพร้อมกัน (Rising Together) เป็นการเชิญชวนให้ทุกคนกลับมาอยู่กับตัวเองเพื่อเชื่อมต่อซึ่งกันและกันอย่างมีสมาธิ เอาใจใส่ และกล้าหาญ เพื่อให้เราสามารถรู้สึกถึงจังหวะการเต้น ของหัวใจของการเคลื่อนไหวทั่วโลก และลุกขึ้นมารับมือกับความท้าทายในยุคนี้ไปด้วยกัน

นักสตรีนิยม นักปกป้องสิทธิสตรี ความยุติธรรมทางเพศ LBTQI+ และขบวนการพันธมิตรทั่วโลกกำลังอยู่ ในช่วงหัวเลี้ยวหัวต่อที่สำคัญ คือเผชิญกับแรงตอบโต้สิทธิเสรีภาพที่เคยได้รับก่อนหน้านี้ ช่วงไม่กี่ปีที่ผ่านมา ลัทธิอำนาจนิยมเติบโตอย่างรวดเร็ว การปราบปรามภาคประชาสังคมอย่างรุนแรง และการทำให้สตรีและ นักปกป้องสิทธิมนุษยชนที่มีความหลากหลายทางเพศกลายเป็นอาชญากร สงครามและความขัดแย้งที่ ทวีความรุนแรงขึ้นในหลายส่วนของโลก ความอยุติธรรมทางเศรษฐกิจยังคงดำเนินต่อไป รวมทั้งวิกฤตการณ์ ด้านสุขภาพ นิเวศวิทยาและสภาพภูมิอากาศ

การเคลื่อนไหวของเรากำลังสั่นคลอน และในขณะเดียวกันเราก็พยายามสร้างและดำรงความเข้มแข็งและ อดทนเพื่องานข้างหน้า เราไม่สามารถทำงานนี้โดยลำพังในห้องเล็กๆของเราได้ การเชื่อมต่อและ การเยียวยาจึงเป็นสิ่งสำคัญในการปรับเปลี่ยนความไม่สมดุลของพลังงานและข้อบกพร่องภายในการเคลื่อน ไหวของเราเอง เราต้องทำงานและวางยุทธศาสตร์ในลักษณะที่เชื่อมโยงกัน เพื่อที่เราจะสามารถเติบโต ไปด้วยกันได้ เวที AWID จะส่งเสริมองค์ประกอบสำคัญของการเชื่อมโยงถึงกันกับพลังความสามารถ การเติบโต และการสร้างความเปลี่ยนแปลงของนักสตรีนิยมทั่วโลก

I never knew I have a close family who loves me and wants me to grow, My mum has always been there for me, but I never imagined I would have thousands of families out there who are not related to me by blood.

I found out family are not just people related by blood ties, but people who love you unconditionally, not minding your sexual orientation, your health status, social status, or your race.

Thinking about the precious moments I listened to all my sisters around the world who are strong feminists, people I have not meet physically, but who support me, teach me, fight for me: I am short of words, words cannot express how much I love you mentors and other feminists, you’re a mother, a sister, a friend to millions of girls.

You are amazing, you fought for people you don’t know - and that is what makes you so special.

It gladdens my heart to express this through writing.

I love you all and will continue to love you. I have not seen any one of you physically but it seems we have known each other for decades.

We are feminists and we are proud to be women.

We will keep letting the world know that our courage is our crown.

A love letter from FAITH ONUH, a young feminist from Nigeria

Liliana was a teacher, a weaver, and a well recognized writer from Argentina.

Her trilogy La saga de los confines received several awards and is unique in the fantasy genre for its use and re-imagining of South American Indigenous mythology.

Liliana’s commitment to feminism was expressed in the diverse, rich and strong women voices in her writing, and particularly in her extensive work for young readers. She also took public positions in favour of abortion, economic justice and gender parity.

This calendar invites us to immerse ourselves in the inspiring world of feminist artistry. Each month, as it gently unfolds, brings forth the vivid artwork of feminist and queer artists from our communities. Their creations are not mere images; they are profound narratives that resonate with the experiences of struggle, triumph, and undying courage that define our collective quest. These visual stories, bursting with color and emotion, serve to bridge distances and weave together our diverse experiences, bringing us closer in our shared missions.

This calendar is our call to you: Use it, print it, share it. Let it be a daily companion in your journey, a constant reminder of our interconnectedness and our shared visions for a better world.

Let it inspire you, as it inspires us, to keep moving forward together.

Get it in your preferred language! |

| English |

| Français |

| Español |

| Português |

| عربي |

| Русский |

| Thai |

Benoîte was a French journalist, writer, and feminist activist.

She published more than 20 novels as well as many essays on feminism.

Her first book “Ainsi Soit-Elle” (loosely translated as “As She Is”) was published in 1975. The book explored the history of women’s rights as well as misogyny and violence against women.

Her last book, “Ainsi Soit Olympe de Gouges,” explored women’s rights during the French Revolution, centering on the early French feminist Olympe de Gouges. De Gouges was guillotined in 1793 for challenging male authority and publishing a declaration of women’s rights (“Déclaration Des droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne”) two years earlier.

If your activity is accepted, you will be contacted by the AWID team to assess and respond to interpretation and accessibility needs.

Ana was a strong advocate of women’s rights and worked with a broad cross-section of women, from those in grassroots networks to those in the private sector.

She believed in building bridges across sectors. Ana was a member of the National Network for the Promotion of Women (RNPM), and was active in developing many social programs that address issues such as sexual and reproductive health and rights.

سنعيد التواصل مع الشركاء/ الشريكات السابقين/ات لضمان احترام الجهود السابقة. إذا تغيرت معلومات الاتصال الخاصة بك منذ آخر عملية للمنتدى، فيرجى تحديثنا حتى نتمكن من الوصول إليك.

“But when was the master

ever seduced from power?

When was a system ever broken

by acceptance?

when will the BOSS hand you power with love?

At Jo’Burg, at Cancun or the U.N?

– Molara Ogundipe

Across the different continents and countries, Professor Ogundipe taught comparative literature, writing, gender, and English studies using literature as a vehicle for social transformation and re-thinking gender relations.

A feminist thinker, writer, editor, social critic, poet, and activist Molara Ogundipe succeeded in combining theoretical work with creativity and practical action. She is considered to be one of the leading critical voices on African feminism(s), gender studies and literary theory.

Molara famously coined the concept of “stiwanism’ from the acronym STIWA – Social Transformations in Africa Including Women recognizing the need to move “away from defining feminism and feminisms in relation to Euro-America or elsewhere, and from declaiming loyalties or disloyalties.”

In her seminal work ‘Re-creating Ourselves’ in 1994, Molara Ogundipe (published under Molara Ogundipe-Leslie) left behind an immense body of knowledge that decolonized feminist discourse and “re-centered African women in their full, complex narratives...guided by an exploration of economic, political and social liberation of African women and restoration of female agency across different cultures in Africa.”

In speaking about the challenges she faced as a young academic she said:

”When I began talking and writing feminism in the late sixties and seventies, I was seen as a good and admirable girl who had gone astray, a woman whose head has been spoilt by too much learning".

Molara Ogundipe stood out for her leadership in combining activism and academia; in 1977 she was among the founding members of AAWORD, the Association of Women in Research and Development. In 1982 she founded WIN (Women In Nigeria) to advocate for full “economic, social and political rights” for Nigerian women. She then went on to establish and direct the Foundation for International Education and Monitoring and spent many years on the editorial board of The Guardian.

Growing up with the Yoruba people, their traditions, culture, and language she once said :

“I think the celebration of life, of people who pass away after an achieved life is one of the beautiful aspects of Yoruba culture.”

Molara’s Yoruba ‘Oiki’ praise name was Ayike. She was born on 27 December 1940 and at the age of 78, Molara passed away on 18 June 2019 in Ijebu-Igbo, Ogun State, Nigeria.

إذا كانت مجموعتك أو مؤسستك تتلقى تمويلًا، فقد ترغب في مناقشة الأمر مع الممول/ة الخاص بك الآن إذا كان قادرًا على دعم سفرك ومشاركتك في المنتدى. تخطط العديد من المؤسسات لميزانياتها للعام المقبل في وقت مبكر من عام 2023، لذا من الأفضل عدم تأخير هذه المحادثة للعام المقبل.

Maritza Quiroz Leiva was an Afro Colombian social activist, a community leader and women human rights defender. Among the 7.7 million Colombians internally displaced by 50 years of armed conflict, Maritza dedicated her advocacy work to supporting the rights of others, particularly in the Afro Colombian community who suffered similar violations and displacement.

Maritza was the deputy leader of the Santa Marta Victim's Committee, and an important voice for those seeking justice in her community, demanding reparations for the torture, kidnapping, displacement, and sexual violence that victims experienced during the armed conflict. She was also active in movement for land redistribution and land justice in the country.

On 5 January 2019, Maritza was killed by two armed individuals who broke into her home. She was 60 years old.

Maritza joined five other Colombian social activists and leaders who had been murdered just in the first week of 2019. A total of 107 human rights defenders were killed that year in the country.

ليس هناك اختلاف، نفس الطريقة ونفس الموعد النهائي. يرجى استخدام نفس النموذج لإرسال مقترحك سواء كان ذلك شخصيًا أو عبر الإنترنت أو كليهما (هجين).

Leah Tumbalang was a Lumad woman of Mindanao in the Philippines. The story of Lumad Indigenous peoples encompasses generations of resistance to large-scale corporate mining, protection of ancestral domains, resources, culture, and the fight for the right to self-determination.

Leah was a Lumad leader as well as a leader of Kaugalingong Sistema Igpasasindog to Lumadnong Ogpaan (Kasilo), a Lumad and peasant organization advocating against the arrival of mining corporations in Bukidnon, Mindanao province. She was unwavering in her anti-mining activism, fervently campaigning against the devastating effects of mineral extraction on the environment and Indigenous peoples’ lands. Leah was also an organizer of the Bayan Muna party-list, a member of the leftist political party Makabayan.

For almost a decade, Leah (along with other members of Kasilo) had been receiving threats for co-leading opposition against the deployment of paramilitary groups believed to be supported by mining interests.

“Being a Lumad leader in their community, she is at the forefront in fighting for their rights to ancestral land and self-determination.” - Kalumbay Regional Lumad Organization

Being at the forefront of resistance also often means being a target of violence and impunity and Leah not only received numerous death threats, but was murdered on 23 August 2019 in Valencia City, Bukidnon.

According to a Global Witness report, “the Philippines was the worst-affected country in sheer numbers” when it comes to murdered environmental activists in 2018.

Read the Global Witness report, published July 2019