Saskia Poldervaart

Over the past few years, a troubling new trend at the international human rights level is being observed, where discourses on ‘protecting the family’ are being employed to defend violations committed against family members, to bolster and justify impunity, and to restrict equal rights within and to family life.

The campaign to "Protect the Family" is driven by ultra-conservative efforts to impose "traditional" and patriarchal interpretations of the family, and to move rights out of the hands of family members and into the institution of ‘the family’.

Since 2014, a group of states have been operating as a bloc in human rights spaces under the name “Group of Friends of the Family”, and resolutions on “Protection of the Family” have been successfully passed every year since 2014.

This agenda has spread beyond the Human Rights Council. We have seen regressive language on “the family” being introduced at the Commission on the Status of Women, and attempts made to introduce it in negotiations on the Sustainable Development Goals.

AWID works with partners and allies to jointly resist “Protection of the Family” and other regressive agendas, and to uphold the universality of human rights.

In response to the increased influence of regressive actors in human rights spaces, AWID joined allies to form the Observatory on the Universality of Rights (OURs). OURs is a collaborative project that monitors, analyzes, and shares information on anti-rights initiatives like “Protection of the Family”.

Rights at Risk, the first OURs report, charts a map of the actors making up the global anti-rights lobby, identifies their key discourses and strategies, and the effect they are having on our human rights.

The report outlines “Protection of the Family” as an agenda that has fostered collaboration across a broad range of regressive actors at the UN. It describes it as: “a strategic framework that houses “multiple patriarchal and anti-rights positions, where the framework, in turn, aims to justify and institutionalize these positions.”

When walking in the heart of the Raval district of Barcelona, you might come across Metzineres, a feminist cooperative by and for womxn2 who use drugs surviving multiple situations of vulnerability.

Imagine a place free of stigma, where womxn can be safe. A safe place that provides shelter, support and accompaniment for womxn whose rights are systematically violated by the war on drugs and those who experience violence, discrimination and repression as a result.

Right outside the entrance, passers by and visitors are greeted with a massive chalkboard that outlines tips, tricks, wishes and drawings by drug users. There is also a calendar that boasts a range of activities self-organized by the Metzineres community. Whether it’s hairdressing and cosmetics workshops, radio shows, theater, communal meals offered to the community, or self-defense classes - there is always something going on.

The cooperative provides safe consumption sites as well as utilities that cover people’s basic needs. There are beds, storage spaces, showers, toilets, washing machines and a small outdoor terrace where people can chill or have a goat gardening.

Metzineres operates within a harm reduction framework, which attempts to reduce the negative consequences of using drugs. But harm reduction is so much more than a set of practices: it is a politics anchored in social justice, dignity and rights for people who use drugs.

2 Womxn is a term used by the collective to describe cis and trans women as well as non-binary people

1 |

Provide AWID members, movement partners and funders with an updated, powerful, evidence-based, and action-oriented analysis of the resourcing realities of feminist movements and current state of the feminist funding ecosystem. |

2 |

Identify and demonstrate opportunities to shift more and better funding for feminist organizing, expose false solutions and disrupt trends that make funding miss and/or move against gender justice and intersectional feminist agendas. |

3 |

Articulate feminist visions, proposals and agendas for resourcing justice. |

Dernière mise à jour : 25 avril 2023

VEUILLEZ LIRE ATTENTIVEMENT LE PRÉSENT ACCORD RELATIF AUX MODALITÉS D’UTILISATION (CI-APRÈS « MODALITÉS D’UTILISATION »). CE SITE WEB ET SES SOUS-DOMAINES (CI-APRÈS COLLECTIVEMENT DÉNOMMÉS « SITE WEB »), AINSI QUE LES INFORMATIONS FIGURANT SUR CE SITE WEB ET LES SERVICES ET RESSOURCES DISPONIBLES OU ACCESSIBLES PAR L’INTERMÉDIAIRE DU SITE WEB (CI-APRÈS INDIVIDUELLEMENT UN « SERVICE » ET COLLECTIVEMENT LES « SERVICES ») SONT CONTRÔLÉS PAR L’ASSOCIATION POUR LES DROITS DES FEMMES DANS LE DÉVELOPPEMENT (« AWID »). CES MODALITÉS D’UTILISATION, AINSI QUE TOUTE MODALITÉ SUPPLÉMENTAIRE QUI PEUT VOUS ÊTRE PRÉSENTÉE POUR CONSULTATION ET APPROBATION (CI-APRÈS COLLECTIVEMENT L’« ACCORD »), RÉGISSENT VOTRE ACCÈS À ET VOTRE UTILISATION DES SERVICES. EN FINALISANT LE PROCESSUS DE VOTRE INSCRIPTION, EN NAVIGUANT SUR LE SITE WEB OU EN ACCÉDANT OU EN UTILISANT UN QUELCONQUE SERVICE DE TOUTE AUTRE MANIÈRE, VOUS RECONNAISSEZ (1) AVOIR LU, COMPRIS ET ACCEPTÉ D’ÊTRE LIÉ·E AU PRÉSENT ACCORD, (2) AVOIR L’ÂGE LÉGAL POUR CONCLURE UN CONTRAT AVEC L’AWID, ET (3) DÉTENIR L’AUTORITÉ DE CONCLURE UN ACCORD EN VOTRE NOM OU AU NOM DE L’ENTITÉ JURIDIQUE IDENTIFIÉE LORS DU PROCESSUS D’INSCRIPTION ET DE LIER L’ENTITÉ JURIDIQUE À L’ACCORD. LE TERME « VOUS » FAIT RÉFÉRENCE À LA PERSONNE OU À LADITE ENTITÉ JURIDIQUE, SELON LE CAS. SI VOUS OU, LE CAS ÉCHÉANT, LADITE ENTITÉ JURIDIQUE, N’ACCEPTEZ PAS D’ÊTRE LIÉ·E AU PRÉSENT ACCORD, VOUS, ET LE CAS ÉCHÉANT LADITE ENTITÉ JURIDIQUE, NE POUVEZ ACCÉDER À OU UTILISEZ AUCUN DES SERVICES.

VEUILLEZ NOTER QUE LA SECTION 1.4 (COMMUNICATIONS DE L’AWID) DE L’ACCORD CI-APRÈS INCLUT LA POSSIBILITÉ DE DONNER SON ACCORD POUR LA RÉCEPTION DE COMMUNICATIONS DE NOTRE PART.

VEUILLEZ NOTER QUE L’ACCORD EST SUSCEPTIBLE D’ÊTRE MODIFIÉ PAR L’AWID À SA SEULE DISCRÉTION, ET CE, À TOUT MOMENT. LORSQUE DES MODIFICATIONS SONT RÉALISÉES, L’AWID COPIE L’ACCORD MIS À JOUR, DISPONIBLE SUR LE SITE WEB, ET MET À JOUR LA « DATE DE DERNIÈRE MISE À JOUR » QUI FIGURE EN TÊTE DES PRÉSENTES MODALITÉS D’UTILISATION. SI NOUS OPÉRONS DES MODIFICATIONS SUBSTANTIELLES AU PRÉSENT ACCORD, NOUS INDIQUERONS SUR NOTRE SITE WEB QUE DES MODIFICATIONS SUBSTANTIELLES ONT ÉTÉ APPORTÉES, ET TENTERONS DE VOUS EN AVERTIR EN VOUS ENVOYANT UN COURRIEL À L’ADRESSE ÉLECTRONIQUE COMMUNIQUÉE AU MOMENT DE LA CRÉATION DE VOTRE COMPTE (SI NOUS EN AVONS UNE). TOUTE MODIFICATION DE L’ACCORD ENTRERA EN VIGUEUR IMMÉDIATEMENT POUR LES PERSONNES NOUVELLEMENT INSCRITES ET LES UTILISATEUR·TRICES ENREGISTRÉ·ES DES SERVICES, ET POUR LES PERSONNES DÉJÀ INSCRITES AU PLUS TÔT (A) TRENTE (30) JOURS APRÈS LA « DATE DE DERNIÈRE MISE À JOUR » FIGURANT EN TÊTE DES PRÉSENTES MODALITÉS D’UTILISATION OU (B) AU MOMENT DE VOTRE CONSENTEMENT ET ACCEPTATION DE L’ACCORD MIS À JOUR SI L’AWID MET À DISPOSITION UN MÉCANISME VOUS PERMETTANT D’ACCEPTER IMMÉDIATEMENT ET SPÉCIFIQUEMENT (TEL QUE PAR UNE ACCEPTATION PAR MULTIPLES CLICS), DONT L’AWID POURRAIT AVOIR BESOIN AVANT DE VOUS AUTORISER À CONTINUER À UTILISER LES SERVICES. SI VOUS N’ACCEPTEZ PAS L’ACCORD MIS À JOUR, VOUS DEVEZ ARRÊTER D’UTILISER L’ENSEMBLE DES SERVICES À LA DATE D’ENTRÉE EN VIGUEUR DE L’ACCORD MIS À JOUR. DANS LE CAS CONTRAIRE, VOTRE UTILISATION CONTINUE DE TOUT SERVICE APRÈS LA DATE D’ENTRÉE EN VIGUEUR DE L’ACCORD MIS À JOUR SIGNIFIE QUE VOUS ACCEPTEZ L’ACCORD MIS À JOUR. VEUILLEZ CONSULTER LE SITE WEB RÉGULIÈREMENT POUR CONSULTER L’ACCORD EN VIGUEUR AU MOMENT DE VOTRE VISITE. VOUS ACCEPTEZ QUE LE FAIT QUE L’AWID CONTINUE À FOURNIR DES SERVICES CONSTITUE UNE CONTREPARTIE SUFFISANTE DES MODIFICATIONS APPORTÉES À L’ACCORD MIS À JOUR.

1. UTILISATION DES SERVICES. Les Services, et les informations et contenus ainsi rendus disponibles, sont protégés par les lois relatives à la propriété intellectuelle en vigueur. Sauf en cas de licence distincte conclue entre vous-même et l’AWID, votre droit d’utiliser un quelconque et tous les Services est soumis aux modalités de l’Accord.

1.1 Licence pour les Services. Sous réserve de votre respect des modalités de l’Accord, l’AWID vous accorde une licence incessible, non transférable, ne pouvant donner lieu à l’octroi de sous-licences, révocable et non exclusive pour l’utilisation des Services de la manière permise par l’Accord.

1.2 Mises à jour. Vous comprenez que les Services évoluent. Vous reconnaissez et acceptez que l’AWID peut mettre les Services à jour en vous avertissant ou non.

1.3 Certaines restrictions. Les droits qui vous sont accordés dans le cadre de l’Accord sont soumis aux restrictions suivantes : (a) il vous est interdit de concéder une licence, vendre, louer, donner à bail, transférer, attribuer, reproduire, distribuer, héberger ou exploiter commercialement de toute autre manière quelque Service que ce soit; (b) il vous est interdit de cadrer ou d’utiliser des techniques de cadrage pour entourer une quelconque marque déposée, logo ou autre élément des Services (dont des images, du texte, de la mise en page ou un formulaire); c) il vous est interdit d’utiliser des métaétiquettes ou autre « texte masqué » utilisant le nom ou les marques déposée de l’AWID; d) il vous est interdit de modifier, traduire, adapter, fusionner ou réaliser des œuvres dérivées de, désassembler, décompiler, procéder à une compilation inverse ou procéder à une ingénierie inverse de toute partie des Services, sauf dans la mesure où les restrictions précédentes sont expressément interdites par la loi en vigueur; e) il vous est interdit d’utiliser tout logiciel, tout appareil ou autres processus manuels ou automatisés (incluant, sans s’y limiter, les araignées, robots, racleurs, robots d’indexation, avatars, outils d’exploration de données ou similaires) pour « racler » ou télécharger des données de toute page Web contenue dans les Services (sauf pour les opérateurs de moteurs de recherche publics auxquels nous octroyons une permission révocable d’utiliser des araignées pour copier des éléments du site Web dans le seul objectif de, et uniquement dans la mesure du nécessaire à la création d’indices de recherche publique, mais non de caches ou d’archives de tels éléments); f) sauf tel que déclaré aux présentes, aucune partie des Services ne peut être copiée, reproduite, distribuée, republiée, téléchargée, affichée, postée ou transmise sous quelque forme ou de quelque moyen que ce soit; et h) il vous est interdit de retirer ou détruire tout avis de droits d’auteur·trice ou autres indications de propriétaire figurant sur ou dans les Services. Toute autre publication, mise à jour ou addition aux Services sera assujettie au présent Accord. L’AWID, ses fournisseurs et prestataires de services se réservent l’ensemble des droits qui ne sont pas octroyés dans l’Accord.

1.4 Communications de l’AWID. En concluant le présent Accord ou en utilisant les Services, vous acceptez de recevoir des communications de notre part, notamment par courriel. Les communications de notre part et de celles de nos entreprises affiliées peuvent inclure, sans s’y limiter, des communications opérationnelles relatives à votre utilisation des Services ainsi que des courriels promotionnels. SI VOUS SOUHAITEZ NE PLUS RECEVOIR DE COURRIELS PROMOTIONNELS, VOUS POUVEZ VOUS DÉSINSCRIRE DE NOTRE LISTE DE COURRIELS PROMOTIONNELS EN SUIVANT LE BOUTON DE DÉSINSCRIPTION FIGURANT DANS CHACUN DE CES COURRIELS.

2. INSCRIPTION.

2.1 Création de votre Compte. Il vous faudra peut-être, pour accéder à certaines des caractéristiques des Services, devenir un·e Utilisateur·trice enregistré·e. Pour les besoins du présent Accord, un·e « Utilisateur·trice enregistré·e » est un·e utilisateur·trice qui a créé un compte auprès de l’AWID par le biais de ses Services (« Compte »).

2.2 Données d’inscription. En créant un Compte, vous acceptez de (a) fournir des informations vraies, précises, actuelles et complètes vous concernant, comme demandé dans le formulaire d’inscription (les « Données d’enregistrement »); et de (b) tenir à jour vos Données d’enregistrement afin qu’elles demeurent vraies, précises, actuelles et complètes. Vous déclarez (i) avoir au moins dix-huit (18) ans; (ii) avoir l’âge légal pour conclure un contrat contraignant; et (iii) ne pas être interdit·e d’utiliser les Services au titre des lois en vigueur aux États-Unis, au Canada, dans votre lieu de résidence ou dans toute autre juridiction concernée. Vous êtes responsable de toutes les activités qui ont lieu par le biais de votre Compte. Vous acceptez de surveiller votre Compte afin d’en limiter l’utilisation par d’autres personnes, notamment des personnes mineures, et acceptez l’entière responsabilité d’une telle utilisation non autorisée. Vous ne pouvez communiquer l’identifiant ou mot de passe de votre Compte à quiconque, et acceptez (y) d’avertir immédiatement l’AWID de toute utilisation non autorisée de votre mot de passe ou autre infraction de sécurité; et (z) de vous déconnecter de votre Compte à la fin de chaque session. Si vous fournissez des informations qui sont erronées, imprécises, obsolètes ou incomplètes, ou si l’AWID a des motifs raisonnables de soupçonner que toute information fournie est erronée, imprécise, obsolète ou incomplète, l’AWID a le droit de suspendre ou supprimer votre Compte et de vous refuser tout accès à l’utilisation actuelle ou future des Services (ou toute partie de ces Services). Vous acceptez de ne pas créer de Compte à l’aide d’une fausse identité ou de fausses informations, ou au nom d’une autre personne que vous-même. Vous acceptez de ne pas créer de Compte ou utiliser les Services si l’AWID vous en a précédemment retiré l’accès, ou si tout Service vous a précédemment été interdit.

2.3 Votre Compte. Nonobstant toute mention contraire aux présentes, vous reconnaissez et acceptez que vous ne détiendrez pas la propriété ou tout autre intérêt de possession de votre Compte, et vous reconnaissez et acceptez en outre que l’ensemble des droits relatifs à et inclus dans votre Compte sont, et demeureront toujours, la propriété de l’AWID, qui en tirera toujours les bénéfices.

2.4 Équipements et logiciels nécessaires. Vous devez fournir tous les équipements et logiciels nécessaires à la connexion aux Services. Vous êtes l’unique responsable de tous les frais d’accès aux Services, et notamment de connexion à l’Internet ou de téléphonie mobile.

3. PROPRIÉTÉ.

3.1 Services. L’AWID et ses fournisseurs sont titulaires de tous les droits, titres et intérêts à l’égard des Services, et les Services sont protégés par les droits de propriété intellectuelle dans le monde entier. Vous acceptez de ne pas retirer, modifier ou masquer toute indication de droits d’auteur·trice, de marque déposée, de marque de service ou autre mention de droits de propriété incluse dans ou accompagnant les Services.

3.2 Marques déposées. Le nom de l’AWID et toute autre stylisation, graphique, logo, marque de service ou nom commercial utilisé sur ou en lien avec tout Service sont les marques déposées de l’AWID et ne peuvent pas être utilisés sans permission en lien avec vos produits et services ou ceux de tierces parties. Les marques déposées, marques de services ou noms commerciaux de tierces parties qui peuvent apparaître sur ou dans les Services sont la propriété de leur propriétaire respectif·ve.

3.3 Rétroactions. Vous acceptez que l’envoi de toute idée, suggestion, document et/ou proposition à l’AWID (« Rétroactions ») est réalisé à vos propres risques et que l’AWID n’a aucune obligation (et notamment, sans s’y limiter, d’obligation de confidentialité) envers de telles Rétroactions. Vous reconnaissez et garantissez que vous disposez de tous les droits nécessaires à l’envoi de Rétroactions. Vous octroyez aux présentes à l’AWID le droit et la licence entièrement payés, libres de redevances, perpétuels, irrévocables, mondiaux et non exclusifs d’utiliser, de reproduire, de représenter, d’afficher, de distribuer, d’adapter, de modifier, de reformater, de créer des œuvres dérivées à partir de, et toute autre exploitation commerciale ou non commerciale de toute manière que ce soit, toute Rétroaction, et d’octroyer des sous-licences des droits susmentionnés, en lien avec le fonctionnement et l’entretien des Services et/ou des affaires de l’AWID.

4. CONDUITE DE L’UTILISATEUR·TRICE. Vous acceptez, comme condition d’utilisation, de ne pas utiliser un quelconque Service dans tout but interdit par le présent Contrat ou par les lois en vigueur. Vous ne prendrez pas part (ni ne permettrez à une tierce partie de prendre part) à toute action qui : (i) enfreint, fait un mauvais usage ou enfreint de toute autre manière tout droit de propriété intellectuelle, droit de publicité, droit à la vie privée ou tout autre droit de toute personne ou entité; (ii) est illégale, menaçante, abusive, harcelante, diffamatoire, trompeuse, frauduleuse, invasive de la vie privée d’autrui, délictuelle, obscène, blessante ou profane; (iii) constitue une publicité, un pourriel ou un courriel envoyé en nombre non autorisé ou non sollicité; (iv) implique des activités commerciales et/ou des ventes, telles que les concours, tirages au sort, échanges, publicités ou programmes pyramidaux sans l’accord préalable écrit de l’AWID; (v) usurpe l’identité de toute personne ou entité, dont du personnel ou des représentant·es de l’AWID; (vi) interfère avec ou tente d’interférer avec le fonctionnement correct des Services ou qui utilise les Services d’une manière qui n’est pas expressément permise par l’Accord; ou (vii) tente de prendre part à, ou prend part à tout acte potentiellement dangereux à l’encontre des Services, y compris, sans s’y limiter, d’enfreindre ou de tenter d’enfreindre tout paramètre de sécurité des Services, notamment en introduisant des virus, des vers ou tout autre code dangereux semblable dans les Services, ou en interférant ou tentant d’interférer avec l’utilisation des Services par tout·e autre utilisateur·trice, client·e ou réseau, notamment en surchargeant, « inondant », envoyant des pourriels, procédant à des envois massifs de courriels ou en paralysant les Services.

5. DONS. L’AWID peut recevoir des dons de votre part par le biais des Services. Vous devez fournir à l’AWID le numéro de carte de crédit en vigueur (Visa, MasterCard ou de tout autre émetteur que nous acceptons) ou le compte PayPal d’un prestataire de paiement (chacun étant un « Prestataire de paiement ») pour que nous puissions recevoir le don. L’accord avec votre Prestataire de paiement régit votre utilisation de la carte de crédit ou du compte PayPal concerné, et vous devez vous reporter à cet accord, et non au présent Accord, pour déterminer vos droits et responsabilités à cet égard.

6. INDEMNISATION. Vous acceptez d’indemniser et de dégager l’AWID, ses entreprises mères, filiales, dirigeant·es, employé·es, agent·es, partenaires, fournisseurs et concédant·es (chacun·e étant une « Partie de l’AWID » et étant collectivement des « Parties de l’AWID ») de toute perte, tout coût, toute responsabilité et toute dépense (et notamment des honoraires raisonnables de conseil juridique) en lien avec ou émanant d’une ou de toutes les situations suivantes : (a) votre utilisation de tout Service en violation du présent Accord; (b) votre enfreinte de tout droit d’une autre partie, dont tout·e Utilisateur·trice enregistré·e; ou (c) votre enfreinte de toute loi, règle ou règlement en vigueur. L’AWID se réserve le droit, à ses propres frais, d’assurer la défense et le contrôle exclusifs de toute question relative à votre indemnisation, auquel cas vous consentez à coopérer entièrement avec l’AWID afin de faire valoir toutes les défenses disponibles. Cette disposition ne nécessite pas que vous indemnisiez une quelconque des Parties de l’AWID pour toute pratique commerciale inadmissible de la part de ladite Partie ou du fait de la fraude, d’un mensonge, d’une fausse promesse, d’une mauvaise représentation ou d’une dissimulation, d’une suppression ou de l’omission par ladite Partie de tout élément matériel en lien avec tout Service fourni aux présentes. Vous acceptez que les dispositions de la présente section survivent au terme de votre Compte, de l’Accord et/ou de votre accès aux Services.

7. EXONÉRATION DE GARANTIES ET CONDITIONS.

7.1 Tel quel. VOUS COMPRENEZ ET ACCEPTEZ EXPRESSÉMENT QUE, DANS LA MESURE PERMISE PAR LA LOI EN VIGUEUR, VOTRE UTILISATION DES SERVICES A LIEU À VOS PROPRES RISQUES, ET QUE LES SERVICES SONT FOURNIS « TELS QUELS » ET « SELON LA DISPONIBILITÉ », ERREURS COMPRISES. L’AWID REJETTE EXPRESSÉMENT TOUTE GARANTIE, REPRÉSENTATION ET CONDITIONS DE TOUTE SORTE, EXPRESSE OU IMPLICITE, ET NOTAMMENT, SANS S’Y LIMITER, LES GARANTIES OU CONDITIONS IMPLICITES DE QUALITÉ MARCHANDE, D’ADÉQUATION À UN OBJECTIF SPÉCIFIQUE ET DE L’ABSENCE DE CONTREFAÇON PROVENANT DE L’UTILISATION DES SERVICES.

(a) L’AWID NE DONNE AUCUNE GARANTIE, REPRÉSENTATION OU CONDITION QUE : (1) LES SERVICES RÉPONDRONT À VOS EXIGENCES; (2) VOTRE UTILISATION DES SERVICES SERA ININTERROMPUE, PONCTUELLE, SÉCURISÉE ET EXEMPTE D’ERREUR; OU (3) LES RÉSULTATS QUI POURRAIENT ÊTRE OBTENUS SUITE À L’UTILISATION DES SERVICES SERONT PRÉCIS ET FIABLES.

(b) AUCUN CONSEIL ET AUCUNE INFORMATION, À L’ORAL OU À L’ÉCRIT, OBTENU·ES DE L’AWID OU PAR LE BIAIS DES SERVICES NE CONSTITUERONT DE GARANTIE QUI NE SOIT EXPRESSÉMENT FORMULÉE AUX PRÉSENTES.

7.2 Aucune responsabilité pour la conduite de tierces parties. VOUS RECONNAISSEZ ET ACCEPTEZ QUE LES PARTIES DE L’AWID NE SONT PAS RESPONSABLES, ET VOUS ACCEPTEZ DE NE PAS CHERCHER À TENIR LES PARTIES DE L’AWID RESPONSABLES POUR LA CONDUITE DE TIERCES PARTIES, ET NOTAMMENT DES OPÉRATEUR·TRICES DE SITES EXTERNES ET AUTRES UTILISATEUR·TRICES DES SERVICES.

7.3 Supports de tierces parties. Dans le cadre des Services, vous pouvez avoir accès à des supports hébergés par une autre partie. Vous acceptez qu’il est impossible pour l’AWID de surveiller de tels supports et que vous accédez à ces supports à vos propres risques.

8. LIMITATION DE LA RESPONSABILITÉ.

8.1 Exonération de certains dommages. VOUS COMPRENEZ ET ACCEPTEZ QUE, DANS LA LIMITE PRÉVUE PAR LA LOI, EN AUCUN CAS LES PARTIES DE L’AWID NE PEUVENT ÊTRE RESPONSABLES DE TOUTE PERTE DE PROFITS, RECETTES OU DONNÉES, TOUT DOMMAGE INDIRECT, ACCIDENTEL, SPÉCIAL OU CONSÉCUTIF, OU TOUT DOMMAGE OU COÛT DÛ À UNE PERTE DE PRODUCTION OU D’UTILISATION, INTERRUPTION D’ACTIVITÉ OU FOURNITURE DE BIENS OU SERVICES DE SUBSTITUTION, QUE L’AWID AIT ÉTÉ AVERTIE OU NON, DANS CHACUN DES CAS, DE LA POSSIBILITÉ DE TELS DOMMAGES, ÉMANANT OU EN LIEN AVEC LE PRÉSENT ACCORD OU TOUTE COMMUNICATION, INTERACTION OU RÉUNION AVEC D’AUTRES UTILISATEUR·TRICES DES SERVICES, DE TOUTE THÉORIE DE RESPONSABILITÉ. LA LIMITATION DE RESPONSABILITÉ PRÉCÉDENTE NE S’APPLIQUERA PAS À LA RESPONSABILITÉ D’UNE PARTIE DE L’AWID EN CAS DE (I) DÉCÈS OU LÉSIONS CORPORELLES CAUSÉES PAR LA NÉGLIGENCE D’UNE PARTIE DE L’AWID; OU DE (II) TOUTE LÉSION CAUSÉE PAR LA FRAUDE OU LA MAUVAISE REPRÉSENTATION FRAUDULEUSE D’UNE PARTIE DE L’AWID.

8.2 Limite de responsabilité. DANS LA LIMITE PRÉVUE PAR LA LOI, LES PARTIES DE L’AWID NE POURRONT ÊTRE TENUES RESPONSABLES ENVERS VOUS QU’À HAUTEUR DE CENT (100) DOLLARS [MB1] MAXIMUM. LA LIMITATION DE RESPONSABILITÉ PRÉCÉDENTE NE S’APPLIQUERA PAS À LA RESPONSABILITÉ D’UNE PARTIE DE L’AWID EN CAS DE (i) DÉCÈS OU LÉSIONS CORPORELLES CAUSÉES PAR LA NÉGLIGENCE D’UNE PARTIE DE L’AWID; OU DE (ii) TOUTE LÉSION CAUSÉE PAR LA FRAUDE OU LA MAUVAISE REPRÉSENTATION FRAUDULEUSE D’UNE PARTIE DE L’AWID.

8.3 Exclusion de dommages. CERTAINES JURIDICTIONS N’AUTORISENT PAS L’EXCLUSION OU LA LIMITATION DE CERTAINS DOMMAGES. SI CES LOIS S’APPLIQUENT POUR VOUS, CERTAINES DES EXCLUSIONS OU LIMITATIONS SUSMENTIONNÉES, OU TOUTES, PEUVENT NE PAS S’APPLIQUER À VOUS, ET VOUS POURRIEZ JOUIR DE DROITS SUPPLÉMENTAIRES.

8.4 Base de la négociation. LES LIMITATIONS DES DOMMAGES ÉNONCÉES CI-DESSUS SONT DES ÉLÉMENTS FONDAMENTAUX DE LA BASE DE LA NÉGOCIATION ENTRE L’AWID ET VOUS-MÊME.

9. PROCÉDURE DE DEMANDE DANS LE CAS D’ENFREINTE DES DROITS D’AUTEUR·TRICE. L’AWID a pour politique de mettre un terme aux privilèges de membre de tout·e Utilisateur·trice enregistré·e qui enfreint les droits d’auteur·trice de manière répétée dès que la ou le propriétaire des droits d’auteur·trice ou l’agent·e juridique de la ou du propriétaire des droits d’auteur·trice en a rapidement prévenu l’AWID. Sans limites à ce qui précède, si vous pensez que votre travail a été copié ou affiché dans les Services d’une manière qui enfreint les droits d’auteur·trice, veuillez fournir les informations suivantes à notre Agent·e des droits d’auteur·trice : (a) une signature électronique ou physique de la personne autorisée a agi au nom de la ou du propriétaire des intérêts de droits d’auteur·trice; (b) une description du travail protégé par droits d’auteur·trice que vous annoncez avoir été enfreints; (c) une description de l’emplacement des Services portant sur le support que vous annoncez avoir été enfreint; (d) vos adresse, numéro de téléphone et adresse électronique; (e) une déclaration écrite dans laquelle vous dites croire en toute bonne foi que l’utilisation contestée n’est pas autorisée par le ou la propriétaire des droits d’auteur·trice, son agent·e ou la loi; et (f) une déclaration, faite sous peine de parjure, dans laquelle vous affirmez que les informations ci-dessus sont exactes et que vous êtes la ou le propriétaire des droits d’auteur·trice ou êtes autorisé·e à agir au nom du ou de la propriétaire des droits d’auteur·trice. Coordonnées de l’Agent des droits d’auteur·trice de l’AWID pour toute demande relative à une enfreinte des droits d’auteur·trice : Direction des opérations, AWID, 192 Spadina Avenue # 300, Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C2, Canada, dosr@awid.org.

10. CONTRÔLE ET APPLICATION. L’AWID se réserve le droit de : (a) prendre les mesures légales nécessaires, y compris, sans s’y limiter, le renvoi vers les autorités d’application de la loi pour toute utilisation illégale ou non autorisée des Services; et/ou (b) mettre un terme ou suspendre votre accès à tout ou une partie des Services, avec ou sans raison précise, y compris, sans s’y limiter, pour enfreinte du présent Accord.

Si l’AWID prend connaissance d’éventuelles enfreintes de l’Accord de votre fait, l’AWID se réserve le droit d’enquêter sur lesdites enfreintes. Si, suite à l’enquête, l’AWID estime qu’une activité criminelle a eu lieu, l’AWID se réserve le droit de renvoyer l’affaire devant, et de coopérer avec toute autorité juridique pertinente. L’AWID est autorisée, sauf dans la mesure interdite par la loi en vigueur, à divulguer toute information ou document sur ou inclus dans les Services, que l’AWID a en sa possession en lien avec votre utilisation des Services, et ce, afin de (i) respecter les lois, processus juridiques ou demandes gouvernementales applicables; (ii) [MB2] faire appliquer l’Accord; (iii) répondre à vos demandes de service à la clientèle; ou (iv) protéger les droits, la propriété ou la sécurité personnelle de l’AWID, de ses Utilisateur·trices enregistré·es ou du public, ainsi que de l’ensemble des personnels d’application de la loi ou du gouvernement, tel que l’AWID, à sa seule discrétion, estime que cela soit nécessaire ou approprié.

11. DURÉE ET RÉSILIATION.

11.1 Durée. L’Accord commence à la date où vous l’acceptez (tel que décrit dans le préambule ci-dessus) et demeure en vigueur pendant toute la durée de votre utilisation des Services, sauf s’il est résilié avant, conformément à l’Accord.

11.2 Utilisation préalable. Nonobstant ce qui précède, vous reconnaissez aux présentes et acceptez que l’Accord a commencé à la survenance du plus précoce des événements suivants (a) la date de votre première utilisation des Services ou (b) la date où vous avez accepté l’Accord, et qu’il demeure en vigueur pendant toute la durée de votre utilisation des Services, sauf s’il est résilié avant, conformément à l’Accord.

11.3 Résiliation des Services par l’AWID. Si vous avez substantiellement enfreint toute disposition du présent Accord, ou si l’AWID est tenue de le faire en vertu de la loi (p. ex. si la fourniture des Services est, ou devient illégale), l’AWID a le droit de suspendre ou de résilier, immédiatement et sans préavis, tout Service qui vous est fourni. Vous acceptez que toute résiliation motivée le sera à la seule discrétion de l’AWID et que l’AWID ne sera pas tenue responsable envers vous ou toute tierce partie pour la résiliation de votre Compte.

11.4 Résiliation des Services par vous-même. Si vous souhaitez résilier les Services fournis par l’AWID, vous pouvez le faire en (a) notifiant l’AWID à tout moment et (b) fermant votre Compte pour tous les Services que vous utilisez. Votre notification doit être envoyée, par écrit, à l’adresse de l’AWID indiquée ci-après.

11.5 Conséquence de la résiliation. La résiliation de tout Service inclut la suppression de l’accès audit Service et l’empêchement de toute utilisation ultérieure dudit Service. Dès la résiliation de tout Service, votre droit d’utilisation dudit Service prend fin immédiatement. Toutes les dispositions de l’Accord qui, par nature devraient survivre, survivront à la résiliation des Services, y compris, sans s’y limiter, les dispositions de propriété, les exonérations de garantie et les limitations de responsabilité.

11.6 Pas d’inscription ultérieure. Si votre ou vos inscriptions, et votre ou vos capacités d’accès aux Services ou à toute autre communauté de l’AWID, sont interrompues par l’AWID du fait de votre enfreinte de toute partie du présent Accord ou pour une conduite jugée inappropriée pour la communauté, vous acceptez alors de ne pas tenter de vous réinscrire, avec ou sans accès aux Services ou à toute communauté de l’AWID, par le biais d’un autre nom de membre ou de toute autre manière, et vous reconnaissez que vous ne serez pas autorisé·e à recevoir un remboursement des frais en lien avec les Services auxquels l’accès a été résilié. Au cas où vous enfreindriez la phrase qui précède, l’AWID se réserve le droit, à sa seule discrétion, de prendre toute ou toutes les mesures énoncées aux présentes sans vous prévenir ou vous en avertir au préalable.

12. UTILISATEUR·TRICES À L’INTERNATIONAL. Les Services sont accessibles de nombreux pays du monde et peuvent contenir des références à des Services qui ne sont pas disponibles dans votre pays. Ces références n’impliquent pas que l’AWID a l’intention d’annoncer de tels Services dans votre pays. Les Services sont contrôlés et proposés par l’AWID depuis ses locaux au Canada. L’AWID ne peut garantir que les Services sont adaptés ou disponibles à l’utilisation dans d’autres lieux. Les personnes qui accèdent à ou utilisent les Services depuis un autre pays le font selon leur propre volonté et sont responsables du respect de la législation locale.

13. SERVICES DE TIERCES PARTIES. Les Services peuvent contenir des liens vers des sites Web tiers (« Sites Web tiers »), des applications tierces (« Applications tierces ») et des publicités pour des tierces parties (« Publicités tierces »). Lorsque vous cliquez sur le lien vers un Site Web tiers, une Application tierce ou une Publicité tierce, nous ne vous préviendrons pas que vous avez quitté les Services et êtes soumis·es aux conditions générales (notamment les politiques relatives à la vie privée) d’un autre site Web ou autre destination. De tels Sites Web tiers, Applications tierces ou Publicités tierces ne sont pas contrôlés par l’AWID. L’AWID n’est responsable d’aucun Site Web tiers, d’aucune Application tierce ou Publicité tierce. L’AWID ne fournit ces Sites Web tiers, Applications tierces et Publicités tierces qu’à des fins de commodité et n’examine pas, n’approuve pas, ne surveille pas, ne valide pas, ne garantit pas et ne fait aucune déclaration relative aux Sites Web tiers, Applications tierces ou Publicités tierces, ou à tout produit ou service en lien avec ceux-ci ou celles-ci. Vous utilisez les liens contenus dans les Sites Web tiers, Applications tierces et Publicités tierces à vos propres risques. Lorsque vous quittez notre Site Web, le présent Accord et nos politiques ne s’appliquent plus. Vous devriez examiner les conditions et politiques applicables, et notamment les pratiques relatives à la vie privée et à la collecte de données, des Sites Web tiers, Applications tierces et Publicités tierces, et mener toutes les recherches que vous estimez nécessaires ou adaptées avant de procéder à une quelconque transaction avec toute tierce partie.

14. RÈGLEMENT DE DIFFÉRENDS.

14.1 Applicabilité de la convention d’arbitrage. Vous acceptez que tout différend entre vous et nous relatif, de quelque manière que ce soit au présent Accord, soit résolu par un arbitrage contraignant, plutôt que devant un tribunal, mais (1) vous et l’AWID pouvez déposer une réclamation devant la Cour des petites créances si les réclamations sont recevables; et (2) vous ou l’AWID pouvez demander un redressement équitable devant une cour pour contrefaçon ou autre mauvaise utilisation de droits de propriété intellectuelle (notamment pour des marques déposées, dénominations commerciales, noms de domaine, secrets commerciaux, droits d’auteur·trice ou brevets). Cette Convention d’arbitrage s’appliquera, sans limites, à toutes les réclamations qui émanent de, ou ont été formulées avant la Date d’entrée en vigueur effective du présent Accord ou de toute version précédente du présent Accord.

14.2 Règles et instance d’arbitrage. La Loi fédérale sur l’arbitrage régit l’interprétation et l’application de la présente Convention d’arbitrage. Pour initier une procédure d’arbitrage, vous devez nous envoyer une lettre par écrit demandant un arbitrage et décrivant votre réclamation, à l’adresse 192 Spadina Avenue # 300, Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C2, Canada. L’arbitrage sera mené par JAMS, un prestataire établi et alternatif de résolution de différends. Les différends incluant des demandes principales et reconventionnelles pour un montant de controverse ne dépassant pas les 250 000 dollars US[MB3], hors frais juridiques et intérêts, seront soumis à la version la plus récente des Règles et procédures simplifiées d’arbitrage de JAMS, disponibles en anglais [MB4] à l’adresse http://www.jamsadr.com/rules-streamlined-arbitration/. Toute autre demande sera soumise à la version la plus actuelle des Règles et procédures complètes d’arbitrage de JAMS, disponibles à l’adresse http://www.jamsadr.com/rules-comprehensive-arbitration/. Les règles de JAMS sont également disponibles sur www.jamsadr.com[MB5] ou en appelant JAMS au +1-[MB6] 800-352-5267. Si [MB7] JAMS n’est pas disponible pour arbitrer, les parties choisiront une autre instance d’arbitrage. Si l’arbitre estime que vous ne pouvez pas payer les frais de dépôt, administratifs, d’audience et/ou autres de JAMS et que vous ne pouvez en être dispensé·e par JAMS, l’AWID les prendra en charge pour vous.

Vous pouvez choisir d’obtenir un arbitrage mené par téléphone, sur la base de documents écrits ou en personne en un lieu déterminé d’un commun accord. Tout jugement sur la sentence arbitrale peut être consigné dans un quelconque tribunal ayant juridiction.

14.3 Autorité de l’arbitre. Dans les limites de la portée de la Section 14.1, l’arbitre disposera de l’autorité exclusive pour la résolution de tout différend relatif à l’interprétation, l’applicabilité, le caractère exécutoire ou la constitution de ladite Convention d’arbitrage, y compris, sans s’y limiter, toute réclamation selon laquelle tout ou une partie de ladite Convention d’arbitrage est nulle ou annulable. L’arbitre décidera des droits et responsabilités, le cas échéant, vous concernant et concernant l’AWID. La procédure d’arbitrage ne sera intégrée à aucune autre affaire ni adjointe à aucune autre procédure ou partie. L’arbitre a la compétence pour accorder des motions dispositives pour tout ou une partie de toute réclamation ou différend. L’arbitre a la compétence pour octroyer des indemnités pécuniaires ou d’octroyer des mesures ou un dédommagement non pécuniaires à une tierce partie individuelle dans le cadre de la loi applicable, des règles de l’instance d’arbitrage et du présent Accord (incluant la Convention d’arbitrage). L’arbitre publiera une décision écrite et une déclaration de décision décrivant les principales constatations et conclusions sur la base desquelles toute sentence (ou décision de ne pas rendre de sentence) repose, et notamment le calcul de toute indemnité accordée. L’arbitre appliquera la loi en vigueur. L’arbitre a la même compétence pour accorder réparation sur une base individuelle qu’un·e juge dans une cour de justice. La décision de l’arbitre est définitive et contraignante pour vous comme pour nous.

14.4 Renonciation à un procès devant jury. VOUS-MÊME ET L’AWID RENONCEZ PAR LES PRÉSENTES À TOUT DROIT CONSTITUTIONNEL OU PRÉVU PAR LA LOI À INTENTER UN PROCÈS AU TRIBUNAL (AUTRE QUE LA COUR DES PETITES CRÉANCES, TEL QU’ADMIS AUX PRÉSENTES) ET À OBTENIR UN JUGEMENT DEVANT UN·E JUGE OU UN JURY. Vous et l’AWID choisissez au contraire que toutes les réclamations et tous les différends soient résolus par arbitrage dans le cadre de la présente Convention d’arbitrage, sauf tel que précisé à la Section 14.1 ci-dessus. Un·e arbitre peut reconnaître sur une base individuelle d’accorder les mêmes dommages et dédommagements qu’un tribunal et doit respecter la présente Convention, comme le ferait un tribunal. Il n’y a cependant pas de juge ni de jury d’un arbitrage, et l’examen par un tribunal d’une décision d’arbitrage est soumis à un examen très limité.

14.5 Renonciation à un dédommagement collectif ou autre dédommagement non individuel. TOUTES LES DEMANDES ET TOUS LES DIFFÉRENDS INCLUS DANS LA PORTÉE DE LA PRÉSENTE CONVENTION D’ARBITRAGE DOIVENT ÊTRE ARBITRÉ.ES SUR UNE BASE INDIVIDUELLE ET NON PAS SUR UNE BASE COLLECTIVE, SEULS LES DÉDOMMAGEMENTS INDIVIDUELS SONT DISPONIBLES POUR LES DEMANDES COUVERTES PAR LA PRÉSENTE CONVENTION D’ARBITRAGE, ET LES DEMANDES PAR OU CONTRE UN·E AUTRE UTILISATEUR·TRICE NE PEUVENT ÊTRE ARBITRÉES OU INCLUSES À CELLES DE OU CONTRE TOUT·E AUTRE UTILISATEUR·TRICE OU PERSONNE. Si une décision est publiée en déclarant que la loi en vigueur exclut la mise en application de toute partie des limitations de la présente Section 14.5 relatives à une demande donnée de dédommagement, la demande concernée, et uniquement la demande concernée, doit être supprimée de l’arbitrage et présentée devant les tribunaux de la province de l’Ontario ou les tribunaux fédéraux du Canada (selon le cas), conformément à la Section 15.1. Toutes les autres demandes seront arbitrées.

14.6 Droit de renonciation de trente (30) jours. Vous avez le droit de renoncer aux dispositions de la présente Convention d’arbitrage en envoyant rapidement une notification écrite de votre décision de renoncer par courriel à l’adresse info@awid.org ou par courrier postal à l’adresse 192 Spadina Avenue # 300, Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C2, Canada dans les 30 jours suivant le début de votre assujettissement à la présente Convention d’arbitrage. Votre notification doit inclure vos nom et adresse, ainsi qu’une déclaration claire et évidente de votre souhait de renoncer à la présente Convention d’arbitrage. Si vous renoncez à la présente Convention d’arbitrage, toutes les autres parties du présent Accord continuent à s’appliquer. Renoncer à la présente Convention d’arbitrage n’a aucun effet sur aucune autre convention d’arbitrage que vous pourriez avoir conclue avec nous, ou que vous pourriez conclure avec nous à l’avenir.

14.7 Dissociabilité. Sauf tel que prévu à la Section 14.5, si une ou plusieurs parties de la présente Convention d’arbitrage sont jugées invalides ou inapplicables par la loi, ladite ou lesdites parties seront nulles et non avenues et seront supprimées, et le reste de la Convention d’arbitrage continuera à s’appliquer.

14.8 Survie de la Convention. La présente Convention d’arbitrage survivra à la résiliation ou à l’expiration des Modalités ou de votre relation avec l’AWID.

14.9 Modification. Nonobstant toute disposition de la présente Convention qui indiquerait le contraire, nous reconnaissons que si l’AWID procède à des modifications substantielles de la présente Convention d’arbitrage à l’avenir, vous pourrez refuser ces modifications dans les trente (30) jours suivant l’entrée en vigueur desdites modifications en envoyant un courriel à l’AWID à l’adresse suivante info@awid.org ou par courrier postal à l’adresse 192 Spadina Avenue # 300, Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C2, Canada.

15. DISPOSITIONS GÉNÉRALES.

15.1 Loi applicable et lieu de jugement. TOUT DIFFÉREND, TOUTE RÉCLAMATION OU DEMANDE DE DÉDOMMAGEMENT EN LIEN, DE QUELQUE MANIÈRE QUE CE SOIT, AVEC L’UTILISATION DES SERVICES SERA RÉGI ET INTERPRÉTÉ PAR, ET CONFORMÉMENT AUX LOIS DE LA PROVINCE DE L’ONTARIO OU AUX LOIS FÉDÉRALES DU CANADA (SELON LE CAS), SANS ÉGARD AUX PRINCIPES QUI PRÉVOIENT L’APPLICATION DE LA LOI DE TOUTE AUTRE JURIDICTION. Dans la mesure permise dans le cadre de la présente Convention, vous et l’AWID devrez tous·tes deux vous accorder sur le fait que toutes les réclamations et tous les différends émanant de, ou en lien avec la Convention seront plaidés exclusivement dans les tribunaux de la province de l’Ontario ou les tribunaux fédéraux du Canada (selon le cas), et que toutes les parties aux présentes seront expressément soumises à la juridiction personnelle et exclusive de tels tribunaux.

15.2 Communications électroniques. Les communications entre vous-même et l’AWID peuvent avoir lieu par des moyens électroniques, que vous visitiez les Services ou envoyiez des courriels à l’AWID, ou que l’AWID publie des avis sur les Services ou communique avec vous par courriel. À des fins contractuelles, vous (a) acceptez de recevoir des communications de l’AWID en format électronique; et (b) acceptez que l’ensemble des conditions générales, accords, avis, publications et autres communications que l’AWID vous fournit de manière électronique remplissent toute exigence juridique que ces mêmes communications rempliraient, si elles étaient fournies par écrit. Ce qui précède n’affecte nullement vos droits prévus par la loi, y compris, sans s’y limiter, les signatures électroniques prévues dans la loi américaine Global and National Commerce Act, 15 U.S.C. §7001 et suiv. (« E-Sign »).

15.3 Cession. L’Accord, ainsi que vos droits et obligations prévus aux présentes, ne peuvent être cédés, sous-traités, délégués ou transférés d’une autre manière par vous sans l’accord préalable écrit de l’AWID, et toute tentative de cession, de sous-traitance, de délégation ou de transfert en violation de ce qui précède sera nulle et non avenue.

15.4 Force majeure. L’AWID ne sera pas tenue responsable de tout retard ou toute inexécution dus à des causes hors de son contrôle raisonnable, incluant, sans s’y limiter, des catastrophes naturelles, pandémies, guerres, actes de terrorisme, émeutes, embargos, actes d’autorités civiles ou militaires, incendies, inondations, accidents, grèves ou pénuries de transport, carburant, énergie, main-d’œuvre ou matériaux.

15.5 Questions, plaintes et réclamations. Pour toute question, plainte ou réclamation relative aux Services, veuillez nous contacter par courriel à l’adresse info@awid.org ou par courrier postal à l’adresse 192 Spadina Avenue # 300, Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C2, Canada. Nous nous efforcerons de répondre à vos préoccupations. Si vous estimez que vos préoccupations n’ont pas reçu toute l’attention nécessaire, nous vous invitons à nous le faire savoir, afin que nous les réexaminions.

15.6 Choix de la langue. Le choix explicite des parties est que l’Accord et l’ensemble des documents connexes aient été rédigés en anglais, puis traduits en français[MB8] .

15.7 Notifications. Lorsque l’AWID vous demande de fournir une adresse de courriel, vous êtes responsable de fournir à l’AWID votre adresse de courriel la plus récente. Si la dernière adresse de courriel fournie à l’AWID n’est pas valable, ou que pour toute raison elle ne parvient pas à vous faire parvenir les notifications requises/permises par l’Accord, l’envoi par l’AWID du courriel contenant ladite notification constituera néanmoins une notification effective. Vous pouvez notifier [MB9] l’AWID par courriel à l’adresse info@awid.org ou par courrier postal à l’adresse 192 Spadina Avenue # 300, Toronto, Ontario M5T 2C2, Canada. Ladite notification sera considérée avoir été donnée lorsque l’AWID l’aura reçue par courriel ou par lettre remise par un service de livraison de nuit reconnu nationalement ou par courrier de première classe, affranchissement prépayé, à l’adresse mentionnée ci-dessus.

15.8 Omission. Toute omission ou défaut de faire exécuter toute disposition de l’Accord à une occasion ne sera pas interprété comme une omission de toute autre disposition ou de ladite disposition à toute autre occasion.

15.9 Dissociabilité. Si toute partie de l’Accord est jugée invalide ou inexécutable, cette partie sera interprétée de manière à refléter, aussi précisément que possible, l’intention originelle des parties, et les autres parties demeureront en vigueur.

15.10 Contrôle des exportations. Vous ne pouvez utiliser, exporter, importer ou transférer un quelconque des Services, sauf tel qu’autorisé par la loi des États-Unis, les lois de la juridiction dans laquelle vous avez obtenu les Services, ou toute autre loi applicable. En particulier, mais sans s’y limiter, les Services ne peuvent être exportés ou réexportés (a) dans un pays sous embargo américain, ou (b) par toute personne figurant sur la liste des ressortissant·es spécifiquement désigné·es du ministère américain des Finances ou sur la liste des personnes ou la liste des entités refusées du ministère américain du Commerce. En utilisant les Services, vous reconnaissez et garantissez que (i) vous n’êtes pas dans un pays qui est soumis à un embargo du gouvernement américain, ou qui a été qualifié par le gouvernement américain comme un pays « appuyant le terrorisme » et que (ii) vous ne figurez pas sur une quelconque liste de parties interdites ou restreintes du gouvernement américain. Vous n’utiliserez pas non plus les Services pour tout objet interdit par la loi des États-Unis, y compris pour l’élaboration, la conception, la fabrication ou la production de missiles, d’armes nucléaires, chimiques ou biologiques. Vous reconnaissez et acceptez que les produits, services ou technologies fournis par l’AWID sont soumis aux lois et aux réglementations des États-Unis sur le contrôle des exportations. Vous respecterez ces lois et ces réglementations et ne procéderez pas, sans autorisation préalable du gouvernement des États-Unis, à l’exportation, la réexportation ou le transfert de produits, services ou technologies de l’AWID, soit directement ou indirectement, vers un pays qui enfreint lesdites lois et réglementations.

15.11 Plaintes de la clientèle. Conformément à l’alinéa 1789.3 du Code civil de l’État de Californie, vous pouvez transmettre des plaintes à la Complaint Assistance Unit de la Division of Consumer Services du California Department of Consumer Affairs en les contactant par écrit à l’adresse 1625 North Market Blvd., Suite N 112, Sacramento, CA 95834, ou par téléphone en composant le +1 (800) 952-5210.

15.12 Intégralité de l’Accord. Le présent Accord est l’accord final, complet et exclusif conclu entre les parties à propos du sujet traité aux présentes, et prévaut sur et fusionne avec toutes les discussions précédentes entre les parties à propos du sujet traité aux présentes.

Cette information ne sera disponible qu’à l’ouverture de l’inscription.

El cuidado como base de las economías

La pandemia de COVID-19 puso de relieve la crisis mundial de los cuidados y demostró los fracasos del modelo económico dominante que está destruyendo servicios públicos esenciales, infraestructuras sociales y sistemas de atención en todo el mundo.

Cozinha Ocupação 9 Julho, Asociación de Mujeres Afrodescendientes del Norte del Cauca (ASOM) y Metzineres son solo algunos ejemplos de economías de cuidado que centran las necesidades de las personas marginalizadas y la Naturaleza, así como el trabajo de cuidados, el trabajo reproductivo, invisibilizado y no remunerado necesario para garantizar la sostenibilidad de nuestras vidas, nuestras sociedades y nuestros ecosistemas.

There are many reasons why your response to the WITM survey matters. The survey offers the opportunity to share your lived experience of mobilizing funding to support your organizing; claim your power as an expert on how money moves and who it reaches; and contribute to collective and consistent advocacy to funders moving more and better funding. Over the last two decades, AWID’s WITM research has proven to be a key resource for activists and funders. We wholeheartedly invite you to join us in its third iteration to highlight the actual state of resourcing, challenge false solutions, and point out how funding must change for movements to thrive and meet the complex challenges of our times.

This is a French article

- created from the French site

Anglais, français, espagnol et chinois mandarin.

No. Valoramos muchísimo su trabajo, pero no estamos buscando respuestas de fondos de mujeres/feministas por el momento. Alentamos a compartir la encuesta con sus socios beneficiarios y con sus redes feministas.

Notre hommage en ligne met à l’honneur cinq défenseuses des droits humains assassinées au Moyen-Orient ou en Afrique du Nord. Ces défenseuses étaient avocates ou militantes et ont œuvré pour les droits des femmes ou pour les droits civils. Leur mort met en évidence les conditions de travail souvent difficiles et dangereuses dans leurs pays respectifs. Nous vous invitons à vous joindre à nous pour commémorer la vie, le travail et l’activisme de ces femmes. Faites circuler ces mèmes auprès de vos collègues et amis ainsi que dans vos réseaux et twittez en utilisant les hashtags #WHRDTribute et #16Jours.

S'il vous plaît cliquez sur chaque image ci-dessous pour voir une version plus grande et pour télécharger comme un fichier

Nous mettrons le site à jour avec les informations pertinantes le moment venu.

Oui, l’enquête est accessible depuis les téléphones intelligents.

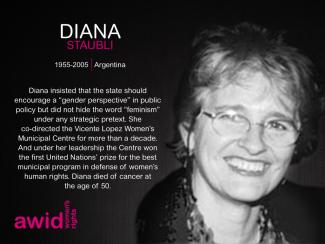

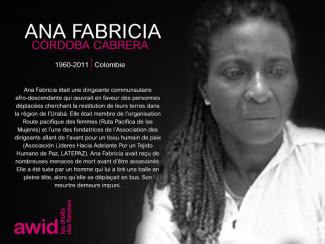

In our 2015 Online Tribute to Women Human Rights Defenders No Longer With Us we are commemorating four women from Sub-Saharan Africa, three of whom were murdered due to their work and/or who they were in their gender identity and sexual orientation. Their deaths highlight the violence LGBT persons often face in the region and across the globe. Please join AWID in honoring these women, their activism and legacy by sharing the memes below with your colleagues, networks and friends and by using the hashtags #WHRDTribute and #16Days.

Please click on each image below to see a larger version and download as a file

Vous N’AVEZ PAS besoin d’un visa pour assister au Forum à Taipei si vous détenez un passeport émis par l’un des pays suivants (la durée de séjour autorisée varie d’un pays à l’autre) :

Allemagne, Andorre, Australie, Autriche, Belgique, Belize, Bulgarie, Brunei, Canada, Chili, Chypre, Croatie, Danemark, Espagne, Estonie, Eswatini, État de la Cité du Vatican, États-Unis, Finlande, France, Grèce, Guatemala, Haïti, Honduras, Hongrie, Îles Marshall, Islande, Irlande, Israël, Italie, Japon*, Lettonie, Liechtenstein, Lituanie, Luxembourg, Malaisie, Malte, Monaco, Nauru, Nicaragua, Norvège, Nouvelle-Zélande, Palaos, Paraguay, Pays-Bas, Philippines, Pologne, Portugal, République de Corée, République dominicaine, République tchèque, Roumanie, Royaume-Uni, Russie, Saint-Christophe-et-Niévès, Sainte-Lucie, Saint-Marin, Saint-Vincent-et-les-Grenadines, Singapour, Slovaquie, Slovénie, Suède, Suisse, Tuvalu.

Les personnes détentrices de tout autre passeport AURONT BESOIN D’UN VISA pour se rendre à Taipei.

Remarque :

Une fois inscrit·e au Forum, il est probable que vous receviez un code relatif à l’événement vous permettant de demander un visa en ligne, quelle que soit votre nationalité.

Nous vous donnerons plus d’informations à ce sujet après l’ouverture du processus d’inscription.