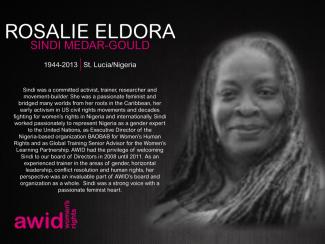

Rosalie Eldora Sindi Medar Gould e

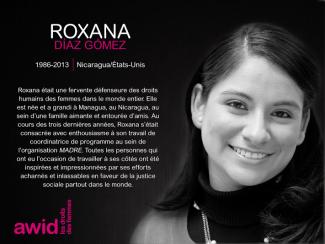

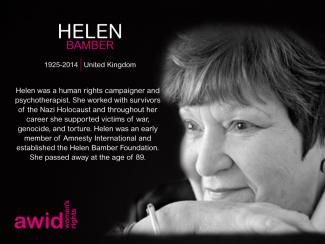

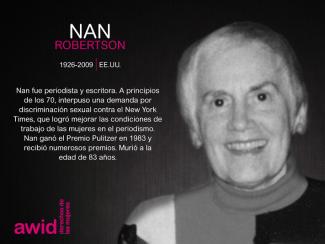

AWID’s Tribute is an art exhibition honouring feminists, women’s rights and social justice activists from around the world who are no longer with us.

This year’s tribute tells stories and shares narratives about those who co-created feminist realities, have offered visions of alternatives to systems and actors that oppress us, and have proposed new ways of organising, mobilising, fighting, working, living, and learning.

49 new portraits of feminists and Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) are added to the gallery. While many of those we honour have passed away due to old age or illness, too many have been killed as a result of their work and who they are.

This increasing violence (by states, corporations, organized crime, unknown gunmen...) is not only aimed at individual activists but at our joint work and feminist realities.

The portraits of the 2020 edition are designed by award winning illustrator and animator, Louisa Bertman.

AWID would like to thank the families and organizations who shared their personal stories and contributed to this memorial. We join them in continuing the remarkable work of these activists and WHRDs and forging efforts to ensure justice is achieved in cases that remain in impunity.

“They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.” - Mexican Proverb

It took shape with a physical exhibit of portraits and biographies of feminists and activists who passed away at AWID’s 12th International Forum, in Turkey. It now lives as an online gallery, updated every year.

To date, 467 feminists and WHRDs are featured.

Cette édition du journal, en partenariat avec Kohl : a Journal for Body and Gender Research (Kohl : une revue pour la recherche sur le corps et le genre) explorera les solutions, propositions et réalités féministes afin de transformer notre monde actuel, nos corps et nos sexualités.

Jessica est une artiste-activiste queer de Toronto, au Canada, mais qui vit actuellement en Bulgarie. Elle a plus de 15 ans d'expérience dans la riposte au VIH, travaillant aux intersections du genre et du VIH auprès de populations clés (travailleurs·ses du sexe, femmes consommatrices de drogues, communautés LGBTQI, personnes incarcérées et, bien sûr, personnes vivant avec le VIH). Jessica aime créer du mouvement et réfléchir/entreprendre/élaborer des stratégies sur des interventions basées sur les arts. L'un des projets amusants qu'elle a lancé en 2013 était LOVE POSITIVE WOMEN (Femmes positives à l’amour), qui implique plus de 125 groupes et organisations communautaires du monde entier, du 1er au 14 février, pour célébrer les femmes vivant avec le VIH dans leurs communautés.

AWID, the Center for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL), and the African Women's Development and Communication Network (FEMNET), offers this think piece to challenge mainstream understandings of development and put forward initial propositions for a feminist agenda for development, economic and gender justice.

Learn more about where this project comes from

These propositions are intended to be just that - proposals, to be discussed, debated, added to, taken apart, adapted, adopted, and even to inspire others.

Leila is a transnational feminist leader, strategist, and advisor with over 25 years of organizing, advocacy and philanthropic experience advancing human rights, gender equality, and sexual and reproductive rights and justice. She was born in Algeria and educated in the U.S., France, and Morocco; over her professional career, she has lived and worked in forty countries across Africa, Europe, Latin America and Asia. Leila currently serves as a Senior International Fellow at the Asfari Institute for Civil Society and Citizenship at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon and as Senior Strategist for various feminist movements and organizations as well as the the Urgent Action Fund-Africa and Trust Africa on an initiative on Reimagining Feminist and Pan-African Philanthropies.

From 2017-2023, Leila held the position as Vice-President of Programs at Global Fund for Women where she oversaw its strategic grantmaking, movement-strengthening, global advocacy and philanthropic collaborations. At GFW, she doubled its grantmaking to over $17 million, launched its feminist and gender-based movements and crises work, created an adolescent girls program led by a girls’ advisory council and led its philanthropic advocacy work. Prior to that she served on the senior leadership team of Ipas from 2002 to 2016 where she published extensively on abortion rights and justice, lead global advocacy efforts and partnered with feminist groups working on self-management, community strategies and stigma reduction around bodily integrity and sexual and reproductive rights.

Leila is currently researching shifts in the philanthropic sector including recognizing non-institutional practices of giving resources in the Global South and efforts to decolonize practices in the Global North. She has written extensively on the political nature of veiling across North Africa and the Middle East, abortion practices in majority Muslim contexts and feminist approaches to sexual and reproductive health, rights and justice.

Leila holds an MPH in public health and a MA in Middle Eastern and North African Studies, studied Islamic law in Morocco and pursued doctoral studies in sociology in France. She studied Arabic and speaks French and English fluently. She is a mother of two feminist young women, an avid scuba diver, mountain bike rider, skier, and outdoor enthusiast.

ภาษาที่ AWID ใช้งานคือ ภาษาอังกฤษ ภาษาฝรั่งเศส และภาษาสเปน โดยภาษาไทยจะถูกเพิ่มเข้ามาในฐานะภาษาท้องถิ่น รวมถึงภาษามือและมาตราการในการช่วยให้เข้าถึงอื่นๆ โดยภาษาอื่นๆอาจถูกเพิ่มเข้ามาหากมีงบประมาณเพียงพอ สามารถเข้ามาดูการอัปเดทว่ามีการเพิ่มภาษาอื่นใดบางได้เรื่อยๆ เราใส่ใจในความยุติธรรมด้านภาษาและจะพยายามให้มีภาษามากที่ที่สุดเท่าที่งบประมาณจะสามารถครอบคลุมได้ เราหวังว่าเราจะสามารถสร้างโอกาสมากมายให้พวกเราสามารถสื่อสารกันหรือนำเสนอในภาษาของตัวเองได้

Deya est faciliteur·rice de mouvement féministe trans queer non binaire, professionnel·le des droits humains et chercheur·se. Son travail se fonde sur des méthodes queer, féministes et participatives. Iel travaille au sein de l’écosystème de financement féministe depuis plus de sept ans et encore plus longtemps au sein des espaces de mouvements féministes – depuis désormais plus d’une décennie. Son travail se situe à l’intersection entre l’argent et les mouvements. Avant de rejoindre l'AWID, Deya était consultant·e indépendant·e auprès de Mama Cash, Kaleidoscope Trust, Comic Relief, Global Fund for Children et d'autres, cocréant des processus, des espaces et des mécanismes de ressources, des programmes et des recherches centrées sur les mouvements. Deya est titulaire d'un LLM (Master of Laws ou Master Legum) en justice internationale et droits humains de l'Université d'Europe centrale.

À l’AWID, Deya dirige la stratégie de soutien et d’engagement des mouvements de Ressources pour les mouvements féministes, et soutient la mise au centre des principaux mouvements féministes en définissant et en menant des programmes de ressourcement féministe. En dehors du travail, Deya est maître-nageur·se, parent d’un chien et adore la fiction littéraire contemporaine.

กรุณาคำนวณค่าใช้จ่ายโดยรวมถึงค่าเดินทางมายังกรุงเทพมหานคร ค่าที่พัก ค่าเบี้ยเลี้ยง ค่าวีซ่า ค่าสนับสนุนในการเข้าถึงต่างๆ และอื่นๆ ยังไม่รวมถึงค่าลงทะเบียนที่จะมีการประกาศเร็วๆนี้ โรงแรมในบริเวณสุขุมวิท กรุงเทพฯ มีราคาตั้งแต่ 1,700-6,800 บาทต่อคืน สำหรับการพักสองคน

โดยหากเป็นสมาชิก AWID จะได้รับส่วนลดค่าลงทะเบียน หากคุณยังไม่ได้เป็นสมาชิก เราขอเชิญชวนให้คุณสมัครสมาชิกและเข้าร่วมชุมชนเฟมินิสต์ระดับโลก

Margarita Salas, AWID

Nazik Abylgaziva, Labrys

Amaranta Gómez Regalado, Secretariado Internacional de Pueblos Indígenas frente al VIH/sida, la Sexualidad y los Derechos Humanos

Cindy Weisner, Grassroots Global Justice Alliance

Lucineia Freitas, Movimento Sem Terra

Nana is a feminist organizer and a reproductive rights and population policy researcher based in Egypt. She is a member of Realizing Sexual and Reproductive Justice (RESURJ), a member of the Advisory Board of the A Project in Lebanon, and a member of the Community Committee of Mama Cash. Nana holds an MSc in Public Health from KIT Institute and Vrije University in Amsterdam. In her work, she follows and contextualizes national population policies while building evidence that addresses modern eugenics, regressive international aid, and authoritarianism. Previously, she was part of the Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, and Ikhtyar Feminist Collective in Cairo.

AWID ฟอรัม ตลอดมาเป็นพื้นที่ที่ไม่กลัวการสนทนาที่จำเป็น หรือหัวข้อที่ท้าทาย เรายินดีรับข้อเสนอเหล่านี้เมื่อผู้จัดกิจกรรมสามารถรักษาพื้นที่สำหรับผู้เข้าร่วมด้วยความเคารพ ปลอดภัย และอย่างระมัดระวัง

AWID began in 1982 and has grown and transformed since then into a truly global organization.

Read From WID to GAD to Women's Rights: The First 20 Years of AWID

เราตระหนักดีถึงอุปสรรคในทางปฏิบัติและความทุกข์ทางอารมณ์ในการเดินทางระหว่างประเทศ โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งจากซีกโลกใต้ โดย AWID กำลังทำงานร่วมกับ TCEB (สำนักงานส่งเสริมการจัดประชุมและนิทรรศการของประเทศไทย) เพื่อสนับสนุนผู้เข้าร่วมฟอรัมในการขอวีซ่า ข้อมูลอื่นๆเกี่ยวกับการขอวีซ่าจะถูกนำเสนอในช่วงที่เปิดให้ลงทะเบียน รวมถึงสถานที่และวิธีการขอวีซ่า