The freedom to decide what to do with our lives

Gabby De Cicco

“My dream is for there to be no more violence against us, no more injustice, and for us to become visible and respected in society and to no longer be stigmatized,” says Rosa Alma Ramos, Salvadoran sex worker and coordinator of the Liquidambar Association of Women Sex Workers of El Salvador.

Rosa’s dream cannot be realized alone, and she has been working with other sex workers who want to see this change and believe there is strength in organizing. Together they are part of an association that has been working towards this dream for close to nine years, and have been an institutional member of AWID since January 2017.

The Beginnings

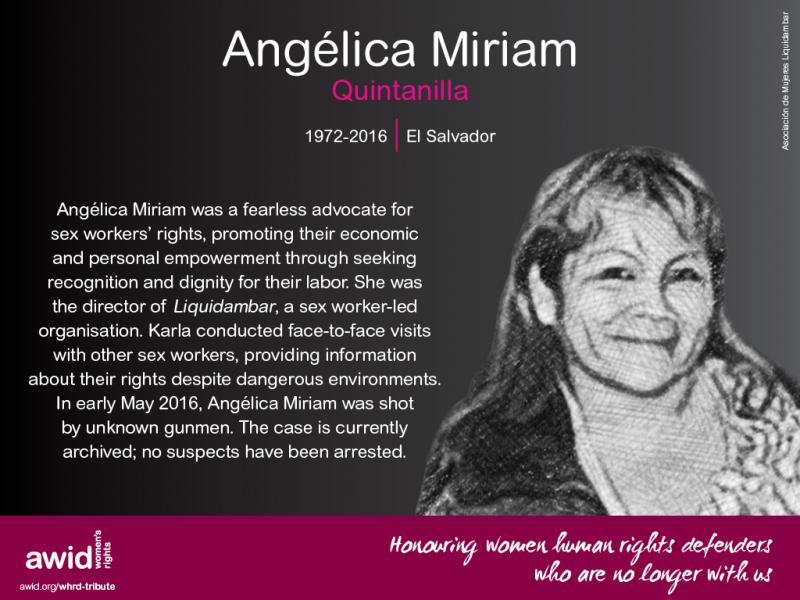

During the 2009 election campaign in El Salvador, the right-wing candidate, Norman Quijanos of the Alianza Republicana Nacionalista party, promised to remove sex workers from the streets of San Salvador. Angélica Quintanilla, a sex worker in that city who was alarmed by these threats, made her way to City Hall together with ten other as-yet-unorganized women, to speak with mayor Violeta Menjívar. That and other conversations led to the creation of the “Sex Worker Violence Prevention Committee,” which would facilitate coordination and dialogue between sex workers, local government, and the police force.

A few months later, the women had organized, and named their new association Liquidambar [sweetgum tree]. “For us that name represents the freedom to decide what to do with our lives and how to achieve our dreams. In our logo you can see a bridge, which represents all the connections or steps we need to take to meet our needs,” explains Rosa with contagious energy. She explains that “the sweetgum tree grows in mountainous areas well above sea level. Those trees have a balsam [“liquid amber”] which runs through their veins down toward the sea, collecting sticks, leaves, and a variety of insects along the way. When it reaches the sea, it is transformed into the only gemstone that comes from a plant: amber. Just as those transformations are as deep and blue as the ocean, so is the strong and beautiful potential and spiritual energy of the woman sex worker.”

Sex Work is Work

Liquidambar began working “without resources or support,” recalls Rosa, until they started forging links with other local and international organizations. From their office in the capital, San Salvador, and with the support of the Foro de ONG en la lucha contra el VIH [NGO Forum Fighting HIV], they are training sex workers in sex education, HIV and STI prevention, and techniques for building self-esteem.

In the Sex Worker Violence Prevention Committee, they lobby different local and national governmental institutions for the implementation of public policies to improve the conditions in which they work.

“The Global Network of Sex Work Projects and the Latin American Platform of People who Exercise Sex Work (PLAPERTS) give us technical support and help us to prepare for participation in international fora, where we advocate for the defense and promotion of sex workers’ human rights.”

As part of activities to mark International Women’s Day, the group issued a statement calling for Congress to debate a bill legalizing sex work, which was delivered to the legislative body by organized sex workers.

Demanding Answers within Feminist Networks

Liquidambar is part of the feminist network Concertación Feminista Prudencia Ayala, which coordinates over 20 feminist organizations in El Salvador, and is linked to Las Dignas and the Salvadoran Network of Women Human Rights Defenders.

“According to the National Constitution, all people are equal before the law, so why are women who are raped revictimized? Why do they keep killing us for being women? Why is there impunity for those femicides?” asks Rosa. “All of this means we need to participate in actions and to learn about and from feminism. That is why we belong to the Red de Defensoras [WHRD network]. As a network, we are demanding that the relevant authorities, such as the Public Prosecutor Office, investigate murder cases so there is no impunity and that these public authorities protect defenders when we file complaints.”

According to a Liquidambar statement, only 10% of women sex workers denounce and follow through on complaints of institutional violence. Among the 90% who do not file complaints, the main reasons cited for doing so were fear of reprisal and lack of confidence in the judicial system.

Beyond Fear

On 6 May 2016 Angélica Quintanilla, the leader who brought together that group of sex workers for the first time in 2009, was murdered. Rosa remembers the founder of Liquidambar as a woman of strong personality who did whatever was necessary to advance her principles and ideas. Her murder is one of the crimes that languish in impunity. Following her death, some of the women left the group, but others remained, convinced of the need to continue resisting as an organized group. Yet the fear was both tangible and strong. Once again, as at the time the association was born, the women of Liquidambar are gathering strength, looking inside, figuring out how to heal and to overcome fear.

Following Angélica’s murder, they had to move their office for security reasons. “We are in a smaller, but cozier office. We have been working hard to overcome the fear that has overtaken us following her murder. The American Jewish World Service (AJWS) helped us through training with a systemic approach to go out with less fear and return to the streets empowered.”

Angélica’s murder is not an isolated case. Liquidambar denounces the 35 recent murders of sex workers in 2018 alone as femicides.

“The threat is so real, we feel it every day. It comes from the gangs, but also from the state and others who think they own the sex work districts.”

Overcoming challenges

Rosa tells us that “the majority of our compañeras come from situations of extreme poverty. Those working in the street encounter threats and demands for ‘fees’ by the gangs just to have the right to work in certain areas, and sometimes the situation leads to a lack of clients.”

In addition, they face institutional violence, the abovementioned femicides, stigma and discrimination on the part of Salvadoran society. “We have been working to raise awareness among uniformed police personnel through trainings, and we use those opportunities to expose those in the force who are violent toward us.”

Liquidambar also carries out projects to fight the poverty facing sex workers, but implementation of some has been complicated by limited funding. The association demands that the local political authorities recognize sex workers and their need for stable employment. “We ask them to offer trainings in entrepreneurship, such as how to make sweets, or to help us set up a day care centre for sex workers’ children.”

Rosa says Liquidambar is raising money as a seed fund to start a cafeteria run by sex workers. “That is a project that has been pending since Angélica’s time.”

The women sex workers of El Salvador are organizing, going out into the streets, and entering decision-making spaces to demand their rights, in order to improve the quality of life of sex workers and their families and dependents. Sex work is work, and it is time for it to be included in state policy.