Diana Staubli

AWID’s Tribute is an art exhibition honouring feminists, women’s rights and social justice activists from around the world who are no longer with us.

This year’s tribute tells stories and shares narratives about those who co-created feminist realities, have offered visions of alternatives to systems and actors that oppress us, and have proposed new ways of organising, mobilising, fighting, working, living, and learning.

49 new portraits of feminists and Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) are added to the gallery. While many of those we honour have passed away due to old age or illness, too many have been killed as a result of their work and who they are.

This increasing violence (by states, corporations, organized crime, unknown gunmen...) is not only aimed at individual activists but at our joint work and feminist realities.

The portraits of the 2020 edition are designed by award winning illustrator and animator, Louisa Bertman.

AWID would like to thank the families and organizations who shared their personal stories and contributed to this memorial. We join them in continuing the remarkable work of these activists and WHRDs and forging efforts to ensure justice is achieved in cases that remain in impunity.

“They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.” - Mexican Proverb

It took shape with a physical exhibit of portraits and biographies of feminists and activists who passed away at AWID’s 12th International Forum, in Turkey. It now lives as an online gallery, updated every year.

To date, 467 feminists and WHRDs are featured.

6 Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) across Western and Southeastern Europe have in their lifetime researched, campaigned, participated in and advanced peace and women’s rights movements be it through political and social activism or through dance. We are grateful for the legacy they have left. Please join AWID in honoring these women, their activism and legacy by sharing the memes below with your colleagues, networks and friends and by using the hashtags #WHRDTribute and #16Days.

Please click on each image below to see a larger version and download as a file

Dado que la encuesta ¿Dónde está el dinero? se centra en las realidades de la dotación de recursos para las organizaciones feministas, la mayoría de las preguntas indagan acerca del financiamiento de tu agrupación entre 2021 y 2023. Para responder la encuesta, necesitarás tener a mano cierta información como, por ejemplo, presupuestos anuales y las fuentes clave de financiamiento.

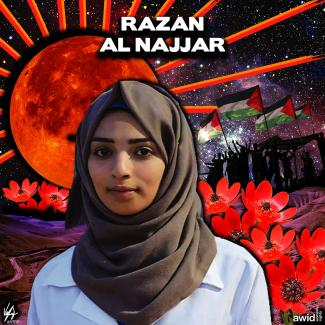

Razan era una médica voluntaria de 21 años en Palestina.

Le dispararon cuando corría hacia un muro fronterizo fortificado, en un intento por llegar hasta una persona herida en el este de la ciudad de Khan Younis, en el sur de Gaza.

En su última publicación en Facebook, Razan dijo: «Estoy volviendo y no retirándome», y añadió: «Denme con sus balas, no tengo miedo».

A framework for your research will guide throughout your research process, and the framing document you develop can also serve as a concept note to advisors and partners, and a funding proposal to potential donors.

Before conducting any research:

- Set the goals of your research

- List the key questions you want your research to answer

- Write out the type of data you will need to obtain and review to answer your key questions

- Define the final products you will produce with your research

Your research framing may evolve over time as you refine your questions and gather new information. However, building an initial research framing will allow you to work from a solid foundation.

To create a strong foundation for your WITM research, it is important to clarify what you hope to accomplish.

For example, one goal of AWID’s WITM global research was to provide rigorous data to prove what we already knew anecdotally: that women’s rights organizations are discrepantly underfunded. With this data, we felt we would be better positioned to influence funders in their decision-making.

Your goals could be to:

Frame your research process with key questions that only your research can answer and limit those questions to a specific time frame (e.g. past five years, past year, etc.).

Consider the following points:

Choosing a specific timeframe for your research can result in more precise findings than working with an open-ended timeframe. Also, deciding whether you will repeat this research at regular intervals will allow you to set up data collection benchmarks for easy replication and comparison over time.

These were the key questions that guided AWID’s WITM research process:

Now that you determined your key questions, you can determine what kind of data will help you answer your key questions. This will allow you to plan the rest of your schedule for your WITM research.

For example, will you conduct a survey that covers an extensive portion of your priority population? Will you analyze the applications that funders are receiving from a certain region? Will you also conduct interviews (recommended)? By determining the types of data you need, you can reach out to external parties who will provide this data early on, and plot out your full schedule accordingly. Some suggested sources of data could be:

Diverse data sets are a great way to create robust and rich analysis.

The data from AWID’s 2011 Global Survey formed the backbone of our analysis in Watering the Leaves, Starving the Roots report. However, we also collected data from interviews and interactions with several actors in the field, ranging from donors to activists and women’s rights organizations.

In addition to allowing you to set your schedule, creating an initial plan of what products you will develop will also allow you to work out what resources you need.

For example, will you only produce a long research report or will you also create infographics, brochures and presentations? Depending on your products, you may need to hire a design firm, plan events and so on.

These products will also be the tools you use to achieve your goals, so it is important to keep those goals in mind. For example, is your WITM research exclusively intended as an advocacy tool to influence funders? In that case, your products should allow you to engage with funders at a deep level.

Some sample products:

Framing your research to cover goals, key questions, types of data, and final products will allow you to create a well-planned schedule, prepare your resources in advance, and plan a realistic budget.

This will make interactions with external partners easier and allow you to be nimble when unexpected setbacks occur.

• 1 month

• 1 or more Research person(s)

• AWID Research Framing: sample 1

• AWID Research Framing: sample 2

EN CIFRAS

Tout à fait. Vos réponses seront supprimées à la fin du processus de traitement et d’analyse des données. Elles ne seront utilisées qu’à des fins de recherche. Les données ne seront JAMAIS partagées en dehors de l’AWID et ne seront traitées que par le personnel de l’AWID et des consultant·es qui collaborent avec nous à la recherche WITM.

La confidentialité de votre vie privée et votre anonymat sont nos priorités. Notre politique de confidentialité est disponible ici.

Née en 1936 dans le Maryland aux États-Unis, Sue était artiste, activiste et enseignante.

Son art était destiné aux femmes et parlait des femmes. En tant que féministe lesbienne, pendant un temps séparatiste, elle s'est engagée à créer des espaces réservés aux femmes. En 1976, elle a acheté un terrain qui est toujours géré par des femmes qui y séjournent pour créer de l'art. Sue a pris une position farouche sur la question de la protection des femmes et des filles.

Avec son approche révolutionnaire, futuriste et anthropologique, elle remplissait chaque pièce dans laquelle elle entrait avec une intelligence et une excentricité authentiques, ainsi qu’un humour et un esprit impitoyable. Ses idées sur la conscience et la créativité continuent à inspirer beaucoup de gens.

Desk research can be done throughout your research. It can assist you with framing, help you to choose survey questions and provide insights to your results.

In this section

- Giving context

- Building on existing knowledge

- Potential sources for desk research

1. Donors’ websites and annual reports

2. Online sources of information

Conducting desk research throughout your research process can assist you with framing, help you to choose survey questions and provide contextual clarity or interesting insights to your survey results, such as comparing similarities and differences between your survey results and information produced by civil society and donors.

Perhaps you notice trends in your survey data and want to understand them.

For example, your survey data may reveal that organization budgets are shrinking, but it cannot tell you why this is happening. Reviewing publications can give you context on potential reasons behind such trends.

Desk research also ensures you are building your research on the existing knowledge regarding your topic, confirming the validity and relevance of your findings.

They may be complimentary or contradictory to existing knowledge, but they must speak to existing data on the topic.

To ensure comprehensive research of the entire funding landscape related to your topic, look at a diverse set of funding sectors.

You can consider:

- Women’s Funds

- Private and Public Foundations

- International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs)

- Bilateral and Multilateral Agencies

- Private Sector Actors

- Individual Philanthropists

- Crowdfunders

Include any other relevant sectors to this research.

For example, you may decide that it is also important to research local non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

These are direct sources of information about what funders are actually doing and generally contain information on policies and budgets. Researching this before interviewing donors can result in more focused questions and a stronger interview.

• 1-2 months

• 1 or more research person(s)

7. Synthesize your research findings

À l’AWID, nous concevons ces réalités féministes comme les exemples vivants des mondes que nous savons possibles. Nous concevons ces diverses réalités féministes comme des revendications et des incarnations d’espoir et de pouvoir. Elles sont ancrées dans les multiples manières de vivre, de penser et de faire autrement, que ce soit au niveau des expressions quotidiennes de nos modes de vie ou nos manières d'être en relations les un.e.s avec les autres ou au niveau de systèmes alternatifs de gouvernance et de justice.

Les Réalités féministes combattent les systèmes de pouvoir dominants tels que le patriarcat, le capitalisme et la suprématie blanche.

Télécharger le magazine complet (PDF)

The survey is open until the end of August 2024. Please complete it within this timeframe to ensure your responses are included in the analysis.

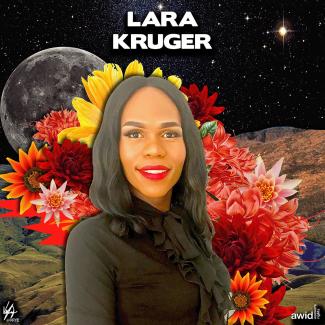

Lara was a well-known and loved radio DJ on Motsweding FM in South Africa.

Lara was one of the first openly-transgender radio hosts on a mainstream station. She worked hard to shine a light on LGBTI issues.

Lara’s activism started at a young age when she would vocally defend her right to dress and behave as she felt comfortable to members of her community who didn’t yet understand what it meant to be transgender.

Pensamos que la economía, el mercado, el sistema financiero y las premisas sobre las que se basan son todas áreas fundamentales para la lucha feminista.

Por eso, nuestra visión de una economía justa va más allá de promover los derechos y el empoderamiento de las mujeres en una economía de mercado, sino que busca evaluar el rol que juegan las opresiones de género en dar forma al modelo económico y ver como podemos transformarlo para garantizar la justicia de género y económica.

No estamos comenzando de cero ni estamos solas en nuestro intento de presentar propuestas feministas para una economía justa. Muchas de nuestras propuestas ya han sido presentadas o existen en la práctica de las diversas comunidades que confrontan y desafían a los sistemas económicos dominantes basados en el mercado y el crecimiento.

También somos concientes de las limitaciones que algunas alternativas presentan para abordar las injusticias del actual sistema capitalista a escala global. No siempre las propuestas a nivel micro son la respuesta a los problemas macro, si bien representan espacios importantes de resistencia y construcción de movimientos.

Sin embargo, las alternativas feministas para una economía justa son fundamentales para socavar el sistema y para aprender a generar cambios transformadores y sistémicos. No podemos presumir de ofrecer un relato exhaustivo ni completo acerca de cómo crear un modelo económico feminista justo, o varios modelos de esa clase. Lo que sí podemos hacer es recoger elementos de diálogos con otros movimientos (sindicales, ambientales, rurales y de campesinxs) para formular propuestas que nos permitan acercanos a esa visión.

El modelo neoliberal que dirige la economía global ha demostrado una y otra vez su incapacidad para hacer frente a las causas estructurales de la pobreza, las desigualdades y la exclusión. Lo que en realidad ha hecho el neoliberalismo ha sido contribuir a crear y exacerbar esas injusticias.

En estas últimas tres décadas, las políticas dominantes para el desarrollo se han caracterizado por la globalización, liberalización, privatizaciones, financialización y ayudas condicionadas, y han destrozado los medios de vida de la población. El recorrido de estas políticas también ha estado marcado por la profundización de desigualdades, las injusticias con marca de género y la destrucción ambiental que el mundo ya no puede continuar soportando.

Hay quienes no dudan en sostener que el crecimiento económico, que debe ser facilitado dando plena libertad a las grandes corporaciones y empresas, puede generar y sostener una una marea alta que (con el tiempo) levante todos los barcos.

Sin embargo, la noción de desarrollo que ha prevalecido durante las últimas décadas, construida sobre la premisa de un crecimiento económico ilimitado, está atravesando una crisis ideológica.

El mito del crecimiento económico como panacea para todos nuestros problemas está perdiendo cada vez más prestigio.

The Nadia Echazú Textile Cooperative carries the name of a pioneer in the struggle for trans rights in Argentina. In many ways, the work of the cooperative celebrates her life and legacy.

Nadia Echazú had a remarkable activist trajectory: she was one of the co-founders of "El Teje", the first trans newspaper in Latin America, alongside Lohana Berkins, Diana Sacayán and Marlene Wayar. Nadia was part of the Argentinian Association of Travestis, Transexual and Transgender people (Asociación de Travestis y Transexuales de Argentina, ATTA) and founded The Organization of Travestis and Transgender People of Argentina (Organización de Travestis y Transexuales de Argentina, OTTRA).

Shortly after her death, her fellow activists founded the cooperative in her name, to honor the deep mark she left on trans and travesti activism in Argentina.