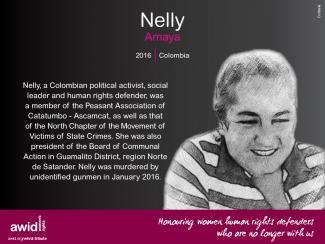

Nelly Amaya

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

Como parte del Viaje por las Realidades Feministas de AWID, te invitamos a explorar nuestro nuevo Club de Cine Feminista: una colección de cortometrajes y largometrajes seleccionados por nuestrxs curadorxs y narradorxs feministas de todo el mundo, que incluyen a Jess X. Snow (Asia-Pacífico), Gabrielle Tesfaye (África/Diáspora Africana) y Esra Ozban (Sudoeste Asiático y África del Norte). Alejandra Laprea es la curadora del programa de América Latina y Centroamérica, que inauguraremos en septiembre, durante el evento de AWID Crear, Résister, Transform: un festival para movimientos feministas. Mientras tanto, ¡mantente atentx a los anuncios sobre proyecciones especiales y conversaciones con cineastas!

Me complace compartir con ustedes una de mis fechas destacadas como feminista con discapacidad. Fue el 30 de mayo de 2014, cuando nosotras, la Nationwide Organization of Visually-Impaired Empowered Ladies (NOVEL) [Organización Nacional de Mujeres con Discapacidad Visual Empoderadas]), participamos en la Semana de la Moda de Filipinas 2014, en el marco de nuestra campaña de promoción del bastón blanco. Dos mujeres ciegas recorrieron la pasarela para promover el bastón blanco como uno de los símbolos de la igualdad de género, el empoderamiento, la plena inclusión y la participación igualitaria en la sociedad de mujeres y niñas con discapacidad visual.

Su desfile frente a la multitud fue para mí una experiencia sumamente impactante, ya que fui quien propuso nuestro proyecto a Runway Productions (esperé pacientemente un año hasta que fue aprobado), sabiendo que ellas no eran modelos: una había sido coronada como Ms. Philippines Vision [Srta. Filipinas Visión], y la otra era la segunda finalista del concurso 2013 de Ms. Philippines on Wheels, Signs and Vision [Srta. Filipinas sobre Ruedas, Señas y Visión] de Tahanang Walang Hagdanan, Inc. (House with No Steps [Casa Sin Escalones]). Dependían de su orientación y ensayaron la noche antes del evento, pero no practicaron con modelos profesionales. Antes de que comenzara el desfile, hablé con ellas por teléfono móvil para estimular su confianza y para rezar juntas pidiendo la ayuda de Dios. Cuando bajaron de la pasarela respiré profundamente y se me caían las lágrimas. ¡Me sentía eufórica porque lo habíamos logrado, a pesar de los desafíos que habíamos tenido que superar! ¡Nuestro mensaje al mundo de que las mujeres y las jóvenes con discapacidad visual pueden caminar con dignidad, libertad e independencia, sobre una base de igualdad con otras, mediante el uso de nuestro dispositivo de asistencia (los bastones blancos) había sido transmitido exitosamente! Fuimos tendencia en las redes sociales, y nos presentaron en los canales de televisión.

Mi vida como feminista con discapacidad comenzó como una forma de sanar mi espíritu quebrantado y de ver un camino diferente para encontrar mi propósito en la vida después de que me convertí en víctima-sobreviviente a causa de un brutal ataque con ácido en 2007, cuando esperaba mi transporte para volver a casa desde la oficina. Mis ojos quedaron severamente dañados, al punto que quedé con la visión reducida.

No sabía cuán plena de alegría y propósito podía ser mi vida nuevamente, hasta que conocí a mujeres líderes del movimiento de género y discapacidad que me convencieron para que continuara. Sus palabras de aliento me atrajeron y fueron la música más dulce para mis oídos. Mi corazón roto salta como un colibrí en vuelo cada vez que pienso en ellas y en el feminismo que me estimuló para participar en hacer la diferencia para nuestras invisibles hermanas con discapacidades y para quienes continúan experimentando discriminación. Al día de hoy me siento consumida por el deseo de estar con el movimiento. No puedo ocultar mi entusiasmo cada vez que presento propuestas de proyectos a diferentes sectores involucrados, a favor del empoderamiento, el desarrollo y el fomento de nuestras hermanas con discapacidades y cuando me presento en coloquios locales, nacionales e internacionales para difundir nuestras voces, incluso a mi costo y cargo.

Inesperadamente, fui seleccionada como representante mujer de nuestro país ante la Asamblea General 2012 de la Unión Mundial de Ciegos (WBU en inglés) en Tailandia, a pesar de que era una recién llegada al movimiento de personas con discapacidad. Me sentí inspirada para conectarme, reunir y empoderar a nuestras hermanas con discapacidad visual respecto de sus derechos, y para conocer sus problemas interrelacionados. En 2013, lanzamos oficialmente la Nationwide Organization of Visually-Impaired Empowered Ladies (NOVEL) para apoyar el empoderamiento de nuestras hermanas con discapacidades, construir coaliciones con movimientos de mujeres y de discapacidades diversas y promover el desarrollo inclusivo del género y la discapacidad.

Mi participación como co-representante de las mujeres con discapacidades en la presentación del Informe Sombra CEDAW, convocado en 2016 por la Oficina Legal y de Derechos Humanos de las Mujeres (WLB, por sus siglas en inglés) con los grupos marginalizados de mujeres, me abrió muchas puertas, tales como el trabajo con diferentes organizaciones de mujeres y la asistencia a los Días Internacionales de la Inclusión 2017 en Berlín, Alemania, junto con tres líderes filipinas con discapacidades, para compartir nuestras buenas prácticas y, principalmente, nuestro compromiso con el movimiento de mujeres de nuestro país.

Mi recorrido como feminista con discapacidad ha sido para mí una montaña rusa emocional. La promoción de la plena inclusión de nuestras hermanas con discapacidades y su participación igualitaria y efectiva en la sociedad me ha dado felicidad y autoestima. También me he sentido frustrada y disgustada cada vez que di todo de mí y recibí a cambio comentarios negativos. No obstante, me siento así porque estoy enamorada del movimiento.

Me veo en el futuro trabajando en solidaridad con el movimiento para garantizar que nuestras hermanas con y sin discapacidades puedan disfrutar y participar en la sociedad de forma completa e igualitaria.

Mucho amor,

Gina Rose P. Balanlay

Feminista con discapacidad

Filipinas

Les organisations féministes et de défense des droits des femmes ne dépendent pas uniquement des financements institutionnels, elles s’autofinancent. Nos mouvements sont animés par la passion, la solidarité, l’engagement politique et le soin collectif.

Ces ressources autonomes et autogénérées sont souvent invisibles dans les budgets, mais elles sont le pilier de notre action collective.

¡Sí! Por favor lee la Convocatoria de Actividades y presenta tu propuesta aquí. La fecha límite es el 1ero de febrero de 2024.

While fundamentalisms, fascisms and other systems of oppression shapeshift and find new tactics and strategies to consolidate power and influence, feminist movements continue to persevere and celebrate gains nationally and in regional and international spaces.

L'AWID fait partie d'un incroyable écosystème de mouvements féministes qui œuvrent pour la justice de genre et la justice sociale dans le monde entier. Avec notre 40e anniversaire, nous célébrons tout ce que nous avons construit au cours de ces 40 dernières années. En tant qu'organisation mondiale de soutien aux mouvements féministes, nous savons que la collaboration avec des féminismes féroces est notre moyen d'avancer, en reconnaissant à la fois la multiplicité des féminismes et la valeur d'une volonté de justice féroce et sans faille. L'état du monde et des mouvements féministes appelle à des conversations et des actions courageuses. Nous sommes impatient.e.s de travailler avec nos membres, nos partenaires et nos bailleurs de fonds pour créer les mondes auxquels nous croyons, célébrer les victoires et dire la vérité pour que le pouvoir soit au service des mouvements féministes dans le monde.

Le calendrier féministe 2023 est notre cadeau aux mouvements. Il présente les œuvres d'art de quelques-un.e.s des formidables membres de l'AWID.

Obtenez-le dans votre langue préférée! |

Sélectionnez la qualité d'image |

| English | Téléchargez pour imprimer | Version numérique |

| Français | Téléchargez pour imprimer | Version numérique |

| Español | Téléchargez pour imprimer | Version numérique |

| Português | Téléchargez pour imprimer | Version numérique |

| عربي | Téléchargez pour imprimer | Version numérique |

| Русский | Téléchargez pour imprimer | Version numérique |

Modèles de gouvernance alternative comme moyens de sortir de la crise climatique.

📅 Mercredi 12 novembre 2025

📍 Seminario Mar Nossa Sra Da Assunção, Pará, Brésil

Site web en anglais

Non, il n'est pas nécessaire d'être membre de l'AWID pour y participer, mais les membres de l'AWID bénéficient d'une réduction sur les frais d'inscription ainsi que d'un certain nombre d'autres avantages.

Una colección viva de recursos para apoyar a los movimientos feministas, a personas que diseñan políticas y a aliadxs que resisten a las tendencias fascistas, fundamentalistas y anti-derechos.

How do you react when the world seemingly descends upon you? For Tidinha, it is one where she found herself being able to be heard as she questions the choice of location, while also discovering shared visions and dreams and realizing that she is not alone.

We are in communication with regional, thematic and funder convenings planned for 2023-2024, to ensure flow of conversations and connections. If you are organizing an event and would like to make a connection to the AWID Forum, please get in touch with us!

Vous souhaitez vous rassembler pour renforcer les résistances ? Cette méthodologie de formation propose des exercices de groupes qui renforcent les connaissances et le pouvoir du collectif, avec des adaptations pour répondre à vos besoins.

Cette politique régit toutes les pages hébergées sur le site www.awid.org, et tout autre site web géré par l'AWID, ainsi que les pages d’inscription à ces sites. Elle ne s'applique pas aux pages hébergées par des organisations autres que l'AWID auxquelles nous pouvons nous associer, et dont les politiques de confidentialité peuvent différer. Veuillez lire le document suivant pour comprendre notre politique de confidentialité concernant la nature, le but, l'utilisation et le partage de vos données personnelles collectées via ce site web.

D’une manière générale, vous pouvez naviguer sur ce site web sans nous soumettre vos informations personnelles. Cependant, dans certaines circonstances, nous vous demanderons de nous fournir certaines données personnelles.

Lorsque vous êtes sur le site web et que nous vous demandons des données personnelles, ces informations ne sont pas partagées en dehors de l’AWID.

1.1.1 Les données que vous fournissez pour obtenir des mises à jour de l'AWID :

Lorsque vous vous inscrivez pour avoir accès au site web - par exemple, que vous vous abonnez pour recevoir des courriels de notre part ou que vous demandez à devenir membre – nous vous demandons de fournir des données personnelles telles que votre nom, pays, langue, courriel pour recevoir les mises à jour. Vous nous transmettez ces informations grâce à des formulaires sécurisés et elles sont stockées sur des serveurs sécurisés.

1.1.2 Les données de paiement que vous envoyez pour devenir membre ou vous inscrire à un événement :

En devenant membre ou en vous inscrivant à des événements, vous devrez peut-être également fournir des données de paiement. L’AWID ne stocke aucune information de carte de crédit sur ses serveurs et utilise des systèmes de paiement sécurisés pour traiter ces informations.

1.1.3 Les informations facultatives que vous avez choisi de nous fournir (avec votre consentement) :

Lorsque vous communiquez avec l’AWID ou que vous fournissez des informations facultatives via des formulaires en-ligne ou utilisez le site pour communiquer avec d'autres membres, nous recueillons ces informations et toute information que vous choisissez de donner.

1.1.4 Les données que nous recueillons via des formulaires de contact ou lorsque vous communiquez directement avec nous :

Lorsque vous communiquez avec nous, nous recueillons ces données ainsi que toute autre information que vous choisissez de nous fournir.

Nous collectons et stockons également certaines autres informations concernant l'utilisation de notre site web par nos utilisateurs-trices afin que des tiers puissent nous fournir des rapports et des analyses concernant l'utilisation et les modes de navigation des utilisateurs-trices.

Pour plus d'informations sur les cookies, veuillez consulter la page suivante : www.allaboutcookies.org/fr/.

Si vous ne souhaitez pas recevoir de cookies, vous pouvez facilement modifier le paramétrage de votre navigateur web pour refuser de recevoir des cookies, ou pour demander d’être informé-e lorsque vous recevez un nouveau cookie. Cliquez ici pour voir comment procéder.

L'AWID utilise les informations collectées à propos de vous pour :

Si vous vous êtes abonné-e aux bulletins électroniques de l'AWID ou à des mises à jour par courrier électronique ou si vous êtes devenu-e membre, nous vous enverrons régulièrement des informations, ainsi qu’indiqué dans la section correspondante du site web. Vous pouvez vous désabonner à tout moment des bulletins électroniques ou des mises à jour par courriel en suivant les liens vers les informations de désabonnement incluses dans nos courriels.

L'exactitude des données vous concernant personnellement est importante pour l'AWID. Nous sommes en permanence à la recherche de moyens pour vous faciliter l’accès aux données que l'AWID conserve à votre sujet via notre site web et à la possibilité et les modifier. Si vous changez votre adresse e-mail, ou si l'une des autres informations que nous détenons est inexacte ou n’est plus d’actualité, merci de nous contacter ici.

Si vous avez consenti à ce que l’AWID utilise vos données personnelles, vous pouvez néanmoins changer d’avis à tout moment en nous contactant et en spécifiant l’autorisation que vous annulez. Veuillez noter que le retrait de votre consentement n'affecte pas la légalité des activités de traitement basées sur ce consentement avant son retrait.

Excepté dans le cas détaillé ci-dessous, l'AWID ne divulgue aucune de vos informations personnelles et ne vend ni ne loue des listes contenant vos informations à des tiers. L'AWID peut divulguer des informations quand elle a votre permission de le faire ou dans des circonstances particulières, par exemple lorsqu’elle croit de bonne foi que la loi l'exige.

Nous mettons continuellement en œuvre et mettons à jour les mesures de sécurité administratives, techniques et physiques afin de protéger vos données contre tout accès non autorisé, perte, destruction ou altération de celles-ci. Certaines des mesures de protection que nous utilisons pour protéger vos informations sont les pare-feu, le cryptage des données et les contrôles d'accès aux informations. Si vous savez, ou avez des raisons de croire, que vos informations d'identification AWID ont été perdues, volées, détournées ou autrement compromises, ou en cas d'utilisation non autorisée réelle ou suspectée de votre compte d'adhésion à l’AWID, veuillez nous contacter.

Cette politique est susceptible d’être modifiée de temps à autre. La dernière version de la politique sera postée sur notre site web, ainsi que la date de sa dernière mise à jour. En cas de modification(s) apportées à cette politique, vous recevrez une mise à jour par courriel. Au cas où vous ne seriez pas d'accord avec la politique ainsi révisée, vous aurez la possibilité d'annuler votre (vos) abonnement(s) chez nous. N’hésitez pas à nous contacter. Tous vos commentaires au sujet de cette politique sont les bienvenus !

Dernière mise à jour : mai 2019

Expose corporate capture. Understand false solutions. Build alternatives. Everything you need to run your own "Whose COP Is It?" campaign.

Tan pronto como podamos, compartiremos información sobre el programa, los espacios y la forma en que todo el mundo puede participar en su construcción, en camino hacia el Foro y durante el Foro. Sigue con atención las actualizaciones.