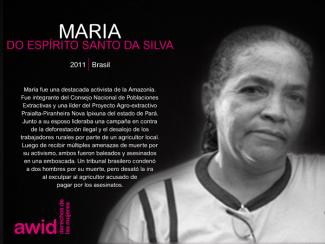

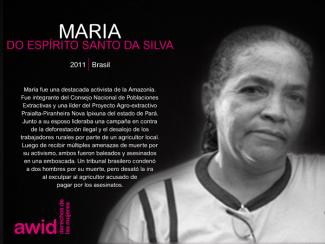

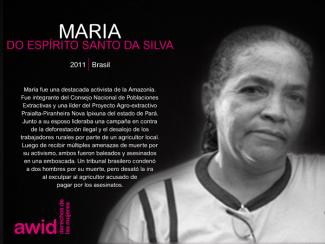

Maria do Espírito Santo da Silva

Building Feminist Economies is about creating a world with clean air to breath and water to drink, with meaningful labour and care for ourselves and our communities, where we can all enjoy our economic, sexual and political autonomy.

In the world we live in today, the economy continues to rely on women’s unpaid and undervalued care work for the profit of others. The pursuit of “growth” only expands extractivism - a model of development based on massive extraction and exploitation of natural resources that keeps destroying people and planet while concentrating wealth in the hands of global elites. Meanwhile, access to healthcare, education, a decent wage and social security is becoming a privilege to few. This economic model sits upon white supremacy, colonialism and patriarchy.

Adopting solely a “women’s economic empowerment approach” is merely to integrate women deeper into this system. It may be a temporary means of survival. We need to plant the seeds to make another world possible while we tear down the walls of the existing one.

We believe in the ability of feminist movements to work for change with broad alliances across social movements. By amplifying feminist proposals and visions, we aim to build new paradigms of just economies.

Our approach must be interconnected and intersectional, because sexual and bodily autonomy will not be possible until each and every one of us enjoys economic rights and independence. We aim to work with those who resist and counter the global rise of the conservative right and religious fundamentalisms as no just economy is possible until we shake the foundations of the current system.

Advance feminist agendas: We counter corporate power and impunity for human rights abuses by working with allies to ensure that we put forward feminist, women’s rights and gender justice perspectives in policy spaces. For example, learn more about our work on the future international legally binding instrument on “transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights” at the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Mobilize solidarity actions: We work to strengthen the links between feminist and tax justice movements, including reclaiming the public resources lost through illicit financial flows (IFFs) to ensure social and gender justice.

Build knowledge: We provide women human rights defenders (WHRDs) with strategic information vital to challenge corporate power and extractivism. We will contribute to build the knowledge about local and global financing and investment mechanisms fuelling extractivism.

Create and amplify alternatives: We engage and mobilize our members and movements in visioning feminist economies and sharing feminist knowledges, practices and agendas for economic justice.

“The corporate revolution will collapse if we refuse to buy what they are selling – their ideas, their version of history, their wars, their weapons, their notion of inevitability. Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing”.

Arundhati Roy, War Talk

The AWID Community is an online social networking platform specifically for AWID. It is a feminist space for connection, resistance and celebration. A space for critical feminist conversations, collective power and solidarity. It is also a space for post-event dialogues, navigating difficult political learnings and community care.

Join AWID membership to be part of the AWID Community today.

Feminist and gender justice movements continue to be chronically underfunded in the face of global funding cuts and freezes. Particularly in Global South regions with shrinking civic spaces, resource scarcity has impacted the most vulnerable communities.

In the face of these setbacks, AWID has updated the Who Can Fund Me? Database - an easy-to-use, practical tool for movements looking for funders from philanthropic foundations, multilateral funders to women’s and feminist funds to support vital lifesaving efforts.

From building prospect funders lists with *templates*, to understand how to write a solid grant proposal, with ‘Getting the Money we Need’ Guide really we don't have to figure this out alone anymore

Read and download the guide hereText-only version

In 2023, feminist and women's rights organizations had a median annual budget of USD 22,000. Behind that median lies disparity and inequality: while a few groups access large-scale resources, the vast majority survive on shoestring budgets.

A closer look at actual budgets reveals major income diversity and inequality.

*Website in French

As world leaders gather in Brazil, feminist movements are advocating, gathering and disrupting the status quo- at COP30 and beyond! We're heading alongside other feminists to Belém, Brazil for COP30, from 10 November – 21 November 2025, where we will continue to denounce false solutions.

Young feminist activists play a critical role in women’s rights organizations and movements worldwide by bringing up new issues that feminists face today. Their strength, creativity and adaptability are vital to the sustainability of feminist organizing.

At the same time, they face specific impediments to their activism such as limited access to funding and support, lack of capacity-building opportunities, and a significant increase of attacks on young women human rights defenders. This creates a lack of visibility that makes more difficult their inclusion and effective participation within women’s rights movements.

AWID’s young feminist activism program was created to make sure the voices of young women are heard and reflected in feminist discourse. We want to ensure that young feminists have better access to funding, capacity-building opportunities and international processes. In addition to supporting young feminists directly, we are also working with women’s rights activists of all ages on practical models and strategies for effective multigenerational organizing.

We want young feminist activists to play a role in decision-making affecting their rights by:

Fostering community and sharing information through the Young Feminist Wire. Recognizing the importance of online media for the work of young feminists, our team launched the Young Feminist Wire in May 2010 to share information, build capacity through online webinars and e-discussions, and encourage community building.

Researching and building knowledge on young feminist activism, to increase the visibility and impact of young feminist activism within and across women’s rights movements and other key actors such as donors.

Promoting more effective multigenerational organizing, exploring better ways to work together.

Supporting young feminists to engage in global development processes such as those within the United Nations

Collaboration across all of AWID’s priority areas, including the Forum, to ensure young feminists’ key contributions, perspectives, needs and activism are reflected in debates, policies and programs affecting them.

Estamos emocianadxs de presentarte a Clemencia Carabalí Rodallega, una feminista afrocolombiana extraordinaria.

Ha trabajado incansablemente durante tres décadas por la salvaguarda de los derechos humanos, los derechos de las mujeres y la construcción de paz en zonas de conflito en la Costa Pacífica de Colombia.

Clemencia ha hecho contribuciones significativas a la lucha por la verdad, la reparación y la justicia para las víctimas de la guerra civil de Colombia.

Recibió el Premio Nacional por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos en 2019, y también participó en la campaña de la recién electa afrocolombiana y amiga de mucho tiempo, la vicepresidenta Francia Márquez.

Aunque Clemencia ha enfrentado y continúa enfrentando muchas dificultades, incluso amenazas e intentos de asesinato, sigue luchando por los derechos de las mujeres y comunidades afrocolombianas en todo el país.

![]()

The survey is available in: Arabic, English, French, Portuguese, Russian and Spanish!

Con más de 10 años de experiencia en finanzas, Lucy ha dedicado su carrera a misiones con y sin fines de lucro. También ha prestado trabajo voluntario para organizaciones sin fines de lucro. Desde el acelerado mundo de las finanzas, Lucy siente pasión por estar al día con las competencias tecnológicas asociadas con este ámbito. Lucy se incorporó a AWID en 2014. En su tiempo libre disfruta de la música, de viajar y de practicar una variedad de deportes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Des militants de Metzineres en action |

La encuesta mundial ¿Dónde está el dinero? es un pilar fundamental de la tercera edición de nuestra investigación orientada a la acción: ¿Dónde está el dinero para las organizaciones feministas? (abreviadamente, ¿Dónde está el dinero? y WITM). Los resultados de la encuesta se desarrollarán y analizarán en mayor profundidad mediante conversaciones exhaustivas con activistas y donantes, y se contrastarán con otros análisis e investigaciones disponibles acerca del estado del financiamiento para las organizaciones feministas y por la igualdad de género en todo el mundo.

El informe completo ¿Dónde está el dinero para las organizaciones feministas? se publicará en 2026.

Para conocer más información acerca de cómo AWID ha arrojado luz sobre el dinero destinado en favor y en contra de los movimientos feministas, consulta nuestra historia ¿Dónde está el dinero? y nuestros informes anteriores aquí.

Para conocer más información acerca de cómo AWID ha arrojado luz sobre el dinero destinado en favor y en contra de los movimientos feministas, consulta nuestra historia ¿Dónde está el dinero? y nuestros informes anteriores aquí.

Kasia soutient le travail des mouvements féministes et de justice sociale depuis 15 ans. Avant de rejoindre l'AWID, Kasia dirigeait les politiques et le plaidoyer d’ActionAid et d’Amnesty International, tout en se mobilisant avec des féministes et des groupes de justice sociale en Pologne pour l'accès à l'avortement et la lutte contre les violences aux frontières européennes. Kasia est passionnée par le ressourcement des organisations féministes dans tout leur courage, leur richesse et leur diversité. Elle partage son temps entre Varsovie et son village communautaire de bricolage dans la forêt. Elle adore les saunas et aime follement son chien Wooly.

Effective as of 25 Apr 2023.

Please click here to view the previous version of our Privacy Policy.

This Privacy Policy describes how the Association for Women’s Rights in Development and our subsidiaries and affiliates (“AWID,” “we,” “us” or “our”) handles personal information that we collect through our website that links to this Privacy Policy (the “Site”), as well as through social media, our marketing activities, our live events and other activities described in this Privacy Policy (“Service”).

Index

Personal information we collect

How we use your personal information

How we share your personal information

Your choices

Other sites and services

Security

International data transfers

Children

Changes to this Privacy Policy

How to contact us

Notice to European users

Information you provide to us. Personal information you may provide to us through the Service or otherwise includes:

Automatic data collection. We, our service providers, and our business partners may automatically log information about you, your computer or mobile device, and your interaction over time with the Service, our communications and other online services, such as:

Cookies and similar technologies. Some of the automatic collection described above is facilitated by cookies, which are small text files that websites store on user devices and that allow web servers to record users’ web browsing activities and remember their submissions, preferences, and login status as they navigate a site. Cookies used on our sites include both “session cookies” that are deleted when a session ends, “persistent cookies” that remain longer, “first party” cookies that we place and “third party” cookies that our third-party business partners and service providers place.

We may use your personal information for the following purposes or as otherwise described at the time of collection:

Service delivery and business operations. We may use your personal information to:

Research and development. We may use your personal information for research and development purposes, including to analyze and improve the Service. As part of these activities, we may create aggregated, de-identified and/or anonymized data from personal information we collect. We make personal information into de-identified or anonymized data by removing information that makes the data personally identifiable to you. We may use this aggregated, de-identified or otherwise anonymized data and share it with third parties for our lawful business purposes, including to analyze and improve the Service and promote our business.

Marketing. We and our service providers may collect and use your personal information to send you direct marketing communications. You may opt-out of our marketing communications as described in the Opt-out of marketing section below.

Compliance and protection. We may use your personal information to:

With your consent. In some cases, we may specifically ask for your consent to collect, use or share your personal information, such as when required by law.

Cookies and similar technologies. In addition to the other uses included in this section, we may use the Cookies and similar technologies described above for the following purposes:

Retention. We generally retain personal information to fulfill the purposes for which we collected it, including for the purposes of satisfying any legal, accounting, or reporting requirements, to establish or defend legal claims, or for fraud prevention purposes. To determine the appropriate retention period for personal information, we may consider factors such as the amount, nature, and sensitivity of the personal information, the potential risk of harm from unauthorized use or disclosure of your personal information, the purposes for which we process your personal information and whether we can achieve those purposes through other means, and the applicable legal requirements.

When we no longer require the personal information we have collected about you, we may either delete it, anonymize it, or isolate it from further processing.

We may share your personal information with the following parties and as otherwise described in this Privacy Policy or at the time of collection.

Affiliates. Our corporate parent, subsidiaries, and affiliates, for purposes consistent with this Privacy Policy.

Service providers. Third parties that provide services on our behalf or help us operate the Service or our business (such as hosting, information technology, customer support, email delivery, marketing, consumer research and website analytics).

Payment processors. Any payment card information you use to make a purchase on the Service is collected and processed directly by our payment processors, such as Stripe. Stripe may use your payment data in accordance with its privacy policy, https://stripe.com/en-gb/privacy. You may also sign up to be billed by your mobile communications provider, who may use your payment data in accordance with their privacy policies.

Third parties designated by you. We may share your personal data with third parties where you have instructed us or provided your consent to do so. We will share personal information that is needed for these other companies to provide the services that you have requested. Moreover, you may choose to translate user-generated content using Google Translate. Google may use your user-generated content in accordance with its privacy policy, https://policies.google.com.Professional advisors. Professional advisors, such as lawyers, auditors, bankers and insurers, where necessary in the course of the professional services that they render to us.

Authorities and others. Law enforcement, government authorities, and private parties, as we believe in good faith to be necessary or appropriate for the compliance and protection purposes described above.

Other users. Your profile and other user-generated content data (except for messages) may be visible to other users of the Service. For example, other users of the Service may have access to your information if you chose to make your profile or other personal information available to them through the Service, such as when you provide comments, reviews, survey responses, or share other content. This information can be seen, collected and used by others, including being cached, copied, screen captured or stored elsewhere by others (e.g., search engines), and we are not responsible for any such use of this information.

In this section, we describe the rights and choices available to all users. Users who are located in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the European Economic Area can find additional information about their rights below.

Opt-out of marketing communications. You may opt-out of marketing-related emails by following the opt-out or unsubscribe instructions at the bottom of the email, or by contacting us. Please note that if you choose to opt-out of marketing-related emails, you may continue to receive service-related and other non-marketing emails.

Declining to provide information. We need to collect personal information to provide certain services. If you do not provide the information we identify as required or mandatory, we may not be able to provide those services.

Delete your content or end your membership. You can choose to delete certain content you have provided to us. If you wish to request to end your membership, please contact us.

The Service may contain links to websites, mobile applications, and other online services operated by third parties. In addition, our content may be integrated into web pages or other online services that are not associated with us. These links and integrations are not an endorsement of, or representation that we are affiliated with, any third party. We do not control websites, mobile applications or online services operated by third parties, and we are not responsible for their actions. We encourage you to read the privacy policies of the other websites, mobile applications and online services you use.

We employ a number of technical, organizational and physical safeguards designed to protect the personal information we collect. However, security risk is inherent in all internet and information technologies and we cannot guarantee the security of your personal information.

We are headquartered in the United States and may use service providers that operate in other countries. Your personal information may be transferred to the United States or other locations where privacy laws may not be as protective as those in your state, province, or country.

Users in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the European Economic Area should read the important information provided below about transfer of personal information outside of the European Union.

The Service is not intended for use by anyone under 18 years of age. If you are a parent or guardian of a child from whom you believe we have collected personal information in a manner prohibited by law, please contact us. If we learn that we have collected personal information through the Service from a child without the consent of the child’s parent or guardian as required by law, we will comply with applicable legal requirements to delete the information.

We reserve the right to modify this Privacy Policy at any time. If we make material changes to this Privacy Policy, we will notify you by updating the date of this Privacy Policy and posting it on the Service or other appropriate means. Any modifications to this Privacy Policy will be effective upon our posting the modified version (or as otherwise indicated at the time of posting). In all cases, your use of the Service after the effective date of any modified Privacy Policy indicates your acknowledgment that the modified Privacy Policy applies to your interactions with the Service and our business.

Where this Notice to European users applies. The information provided in this “Notice to European users” section applies only to individuals located in the EEA or the UK (EEA and UK jurisdictions are together referred to as “Europe”).

Personal information. References to “personal information” in this Privacy Policy should be understood to include a reference to “personal data” (as defined in the GDPR) – i.e., information about individuals from which they are either directly identified or can be identified. It does not include “anonymous data” (i.e., information where the identity of individual has been permanently removed). The personal information that we collect from you is identified and described in greater detail in the section “Personal information we collect”.

Our legal bases for processing. In respect of each of the purposes for which we use your personal information, the GDPR requires us to ensure that we have a “legal basis” for that use.

We have set out below, in a table format, the legal bases we rely on in respect of the relevant Purposes for which we use your personal information – for more information on these Purposes and the data types involved, see How we use your personal information above.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retention. We retain personal information for as long as necessary to fulfill the purposes for which we collected it, including for the purposes of satisfying any legal, accounting, or reporting requirements, to establish or defend legal claims, or for compliance and protection purposes, unless specifically authorized to be retained longer.

To determine the appropriate retention period for personal information, we consider the amount, nature, and sensitivity of the personal information, the potential risk of harm from unauthorized use or disclosure of your personal information, the purposes for which we process your personal information and whether we can achieve those purposes through other means, and the applicable legal requirements.

When we no longer require the personal information, we have collected about you, we will either delete or anonymize it or, if this is not possible (for example, because your personal information has been stored in backup archives), then we will securely store your personal information and isolate it from any further processing until deletion is possible. If we anonymize your personal information (so that it can no longer be associated with you), we may use this information indefinitely without further notice to you.

Other information

No obligation to provide personal information. You do not have to provide personal information to us. However, where we need to process your personal information either to comply with applicable law or to deliver our Services to you, and you fail to provide that personal information when requested, we may not be able to provide some or all of our Services to you. We will notify you if this is the case at the time.

No Automated Decision-Making and Profiling. As part of the Services, we do not engage in automated decision-making and/or profiling, which produces legal or similarly significant effects. We will let you know if that changes by updating this Privacy Policy.

Security. We have put in place procedures designed to deal with breaches of personal information. In the event of such breaches, we have procedures in place to work with applicable regulators. In addition, in certain circumstances (including where we are legally required to do so), we may notify you of breaches affecting your personal information.

Your rights

General. European data protection laws give you certain rights regarding your personal information. If you are located in Europe, you may ask us to take any of the following actions in relation to your personal information that we hold:

Exercising These Rights. You may submit these requests by email. See the How to contact us section above for our contact details. We may request specific information from you to help us confirm your identity and process your request. Whether or not we are required to fulfill any request you make will depend on a number of factors (e.g., why and how we are processing your personal information), if we reject any request you may make (whether in whole or in part) we will let you know our grounds for doing so at the time, subject to any legal restrictions. Typically, you will not have to pay a fee to exercise your rights; however, we may charge a reasonable fee if your request is clearly unfounded, repetitive or excessive. We try to respond to all legitimate requests within a month. It may take us longer than a month if your request is particularly complex or if you have made a number of requests; in this case, we will notify you and keep you updated.

Your Right to Lodge a Complaint with your Supervisory Authority. In addition to your rights outlined above, if you are not satisfied with our response to a request you make, or how we process your personal information, you can make a complaint to the data protection regulator in your habitual place of residence.

The Information Commissioner’s Office

Water Lane, Wycliffe House

Wilmslow - Cheshire SK9 5AF

Tel. +44 303 123 1113

Website: https://ico.org.uk/make-a-complaint/

Data Processing outside Europe; we are a US-based company and many of our service providers, advisers, partners or other recipients of data are also based in the US. This means that, if you use the Services, your personal information will necessarily be accessed and processed in the US. It may also be provided to recipients in other countries outside Europe.

It is important to note that that the US is not the subject of an ‘adequacy decision’ under the GDPR – basically, this means that the US legal regime is not considered by relevant European bodies to provide an adequate level of protection for personal information, which is equivalent to that provided by relevant European laws.

Where we share your personal information with third parties who are based outside Europe, we try to ensure a similar degree of protection is afforded to it in accordance with applicable privacy laws by making sure one of the following mechanisms is implemented:

You may contact us if you want further information on the specific mechanism used by us when transferring your personal information out of Europe.

While in Sao Paulo, Brazil, you can visit the Ocupação 9 de Julho and have a collaborative meal. You can buy their products in their online store from abroad.

Visit the Association of Afro-Descendant Women of the Northern Cauca’s online store where you can find beautiful handcrafted products.

There are several ways to support Metzineres: you can make a financial donation, donate materials and services, or propose a training course, workshop, or activity (for more information, see here).

The key objective of the WITM survey is to shine light on the financial status of diverse feminist, women’s rights, gender justice, LBTQI+ and allied movements globally. Based on this, we hope to further strengthen the case for moving more and better money, as well as shift power, to feminist movements.

Marta is a queer, transfeminist non-binary activist-researcher from ex-Yugoslavia, currently based in Barcelona. They work as a transnational movement organizer, a feminist economist and a weaver of systemic alternatives. They are the co-founder and one of the coordinators of the Global Tapestry of Alternatives, a global process that seeks to identify, document and connect alternatives on local, regional and global levels. Locally, they are engaged in anti-racist, transfeminist, queer, migrant organizing. They also hold a doctoral degree in Environmental Science and Technology from the Autonomous University of Barcelona, dedicated to decolonial feminist perspectives of a pluriverse of systemic alternatives and the creation of feminist alternative systems based on care and the sustainability of life. During their free time, they enjoy boxing, playing the guitar and the drums as part of a samba band, photography, hiking, cooking for loved ones and spoiling their two cats.

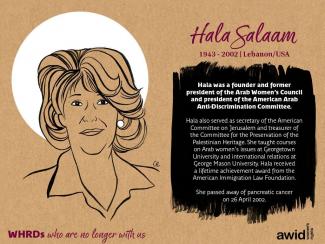

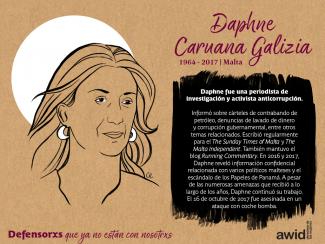

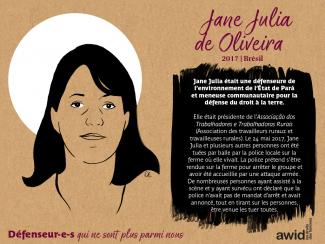

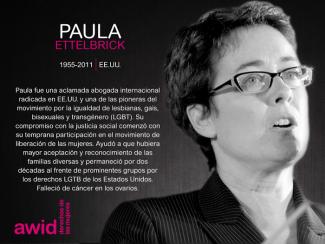

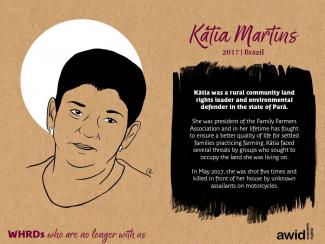

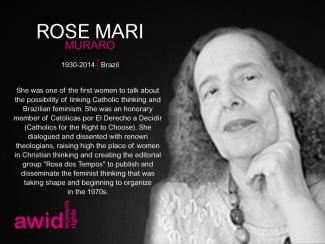

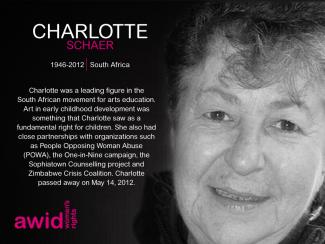

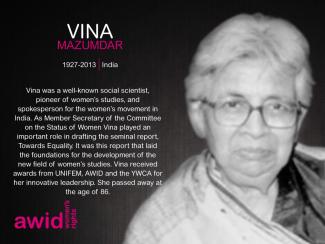

Ces 21 Défenseuses des Droits humains (WHRDs) ont travaillé en tant que journalistes ou plus généralement dans le domaine des médias au Mexique, en Colombie, aux Îles Fidji, en Lybie, au Népal, aux États-Unis, au Nicaragua, aux Philippines, en Russie, en Allemagne, en France, en Afghanistan et au Royaume-Uni. 17 d'entre elles ont été assassinées et les causes de la mort de l’une d’elles restent obscures. Pour cette Journée mondiale de la liberté de la presse, joignez-vous à nous pour commémorer la vie et le travail de ces femmes. Faites circuler ces portraits auprès de vos collègues, vos ami-e-s et dans vos réseaux. Partagez-les en utilisant les mots-clés #WPFD2016 et #WHRDs.

Les contributions de ces femmes ont été célébrées et honorées dans notre Hommage en ligne aux défenseuses qui ne sont plus parmi nous.

Cliquez sur chaque image pour voir une version plus grande ou pour télécharger le fichier.

We believe in a full application of the principle of rights including those enshrined in international laws and affirm the belief that all human rights are interrelated, interdependent and indivisible. We are committed to working towards the eradication of all discriminations based on gender, sexuality, religion, age, ability, ethnicity, race, nationality, class or other factors.

Feminist Realities is a warm and caring invitation, a kind of en masse-care (versus self-care) act of preservation, an invitation to archive, to take stock of all the work lest it disappear. (...)

by Haddy Jatou Gassama

The Mandinka tribe of The Gambia has a custom of measuring the first wrapa used to carry a newborn baby on its mother's back. (...)

artwork: “Sacred Puta” by Pia Love >