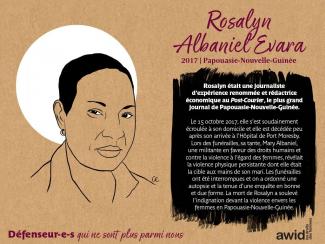

Rosalyn Albaniel Evara

Over the past few years, a troubling new trend at the international human rights level is being observed, where discourses on ‘protecting the family’ are being employed to defend violations committed against family members, to bolster and justify impunity, and to restrict equal rights within and to family life.

The campaign to "Protect the Family" is driven by ultra-conservative efforts to impose "traditional" and patriarchal interpretations of the family, and to move rights out of the hands of family members and into the institution of ‘the family’.

Since 2014, a group of states have been operating as a bloc in human rights spaces under the name “Group of Friends of the Family”, and resolutions on “Protection of the Family” have been successfully passed every year since 2014.

This agenda has spread beyond the Human Rights Council. We have seen regressive language on “the family” being introduced at the Commission on the Status of Women, and attempts made to introduce it in negotiations on the Sustainable Development Goals.

AWID works with partners and allies to jointly resist “Protection of the Family” and other regressive agendas, and to uphold the universality of human rights.

In response to the increased influence of regressive actors in human rights spaces, AWID joined allies to form the Observatory on the Universality of Rights (OURs). OURs is a collaborative project that monitors, analyzes, and shares information on anti-rights initiatives like “Protection of the Family”.

Rights at Risk, the first OURs report, charts a map of the actors making up the global anti-rights lobby, identifies their key discourses and strategies, and the effect they are having on our human rights.

The report outlines “Protection of the Family” as an agenda that has fostered collaboration across a broad range of regressive actors at the UN. It describes it as: “a strategic framework that houses “multiple patriarchal and anti-rights positions, where the framework, in turn, aims to justify and institutionalize these positions.”

مع استمرار الرأسمالية الأبوية الغيريّة في دَفعِنا نحو الاستهلاكية والرضوخ، نجد نضالاتنا تُعزَل وتُفصَل عن بعضها الآخر من خلال الحدود المادّية والحدود الافتراضية على حدٍّ سواء.

Effective as of 25 Apr 2023.

Please click here to view the previous version of our Privacy Policy.

This Privacy Policy describes how the Association for Women’s Rights in Development and our subsidiaries and affiliates (“AWID,” “we,” “us” or “our”) handles personal information that we collect through our website that links to this Privacy Policy (the “Site”), as well as through social media, our marketing activities, our live events and other activities described in this Privacy Policy (“Service”).

You can download a printable copy of this Privacy Policy here.

Index

Personal information we collect

How we use your personal information

How we share your personal information

Your choices

Other sites and services

Security

International data transfers

Children

Changes to this Privacy Policy

How to contact us

Notice to European users

Information you provide to us. Personal information you may provide to us through the Service or otherwise includes:

Automatic data collection. We, our service providers, and our business partners may automatically log information about you, your computer or mobile device, and your interaction over time with the Service, our communications and other online services, such as:

Cookies and similar technologies. Some of the automatic collection described above is facilitated by cookies, which are small text files that websites store on user devices and that allow web servers to record users’ web browsing activities and remember their submissions, preferences, and login status as they navigate a site. Cookies used on our sites include both “session cookies” that are deleted when a session ends, “persistent cookies” that remain longer, “first party” cookies that we place and “third party” cookies that our third-party business partners and service providers place.

We may use your personal information for the following purposes or as otherwise described at the time of collection:

Service delivery and business operations. We may use your personal information to:

Research and development. We may use your personal information for research and development purposes, including to analyze and improve the Service. As part of these activities, we may create aggregated, de-identified and/or anonymized data from personal information we collect. We make personal information into de-identified or anonymized data by removing information that makes the data personally identifiable to you. We may use this aggregated, de-identified or otherwise anonymized data and share it with third parties for our lawful business purposes, including to analyze and improve the Service and promote our business.

Marketing. We and our service providers may collect and use your personal information to send you direct marketing communications. You may opt-out of our marketing communications as described in the Opt-out of marketing section below.

Compliance and protection. We may use your personal information to:

With your consent. In some cases, we may specifically ask for your consent to collect, use or share your personal information, such as when required by law.

Cookies and similar technologies. In addition to the other uses included in this section, we may use the Cookies and similar technologies described above for the following purposes:

Retention. We generally retain personal information to fulfill the purposes for which we collected it, including for the purposes of satisfying any legal, accounting, or reporting requirements, to establish or defend legal claims, or for fraud prevention purposes. To determine the appropriate retention period for personal information, we may consider factors such as the amount, nature, and sensitivity of the personal information, the potential risk of harm from unauthorized use or disclosure of your personal information, the purposes for which we process your personal information and whether we can achieve those purposes through other means, and the applicable legal requirements.

When we no longer require the personal information we have collected about you, we may either delete it, anonymize it, or isolate it from further processing.

We may share your personal information with the following parties and as otherwise described in this Privacy Policy or at the time of collection.

Affiliates. Our corporate parent, subsidiaries, and affiliates, for purposes consistent with this Privacy Policy.

Service providers. Third parties that provide services on our behalf or help us operate the Service or our business (such as hosting, information technology, customer support, email delivery, marketing, consumer research and website analytics).

Payment processors. Any payment card information you use to make a purchase on the Service is collected and processed directly by our payment processors, such as Stripe. Stripe may use your payment data in accordance with its privacy policy, https://stripe.com/en-gb/privacy. You may also sign up to be billed by your mobile communications provider, who may use your payment data in accordance with their privacy policies.

Third parties designated by you. We may share your personal data with third parties where you have instructed us or provided your consent to do so. We will share personal information that is needed for these other companies to provide the services that you have requested. Moreover, you may choose to translate user-generated content using Google Translate. Google may use your user-generated content in accordance with its privacy policy, https://policies.google.com.Professional advisors. Professional advisors, such as lawyers, auditors, bankers and insurers, where necessary in the course of the professional services that they render to us.

Authorities and others. Law enforcement, government authorities, and private parties, as we believe in good faith to be necessary or appropriate for the compliance and protection purposes described above.

Other users. Your profile and other user-generated content data (except for messages) may be visible to other users of the Service. For example, other users of the Service may have access to your information if you chose to make your profile or other personal information available to them through the Service, such as when you provide comments, reviews, survey responses, or share other content. This information can be seen, collected and used by others, including being cached, copied, screen captured or stored elsewhere by others (e.g., search engines), and we are not responsible for any such use of this information.

In this section, we describe the rights and choices available to all users. Users who are located in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the European Economic Area can find additional information about their rights below.

Opt-out of marketing communications. You may opt-out of marketing-related emails by following the opt-out or unsubscribe instructions at the bottom of the email, or by contacting us. Please note that if you choose to opt-out of marketing-related emails, you may continue to receive service-related and other non-marketing emails.

Declining to provide information. We need to collect personal information to provide certain services. If you do not provide the information we identify as required or mandatory, we may not be able to provide those services.

Delete your content or end your membership. You can choose to delete certain content you have provided to us. If you wish to request to end your membership, please contact us.

The Service may contain links to websites, mobile applications, and other online services operated by third parties. In addition, our content may be integrated into web pages or other online services that are not associated with us. These links and integrations are not an endorsement of, or representation that we are affiliated with, any third party. We do not control websites, mobile applications or online services operated by third parties, and we are not responsible for their actions. We encourage you to read the privacy policies of the other websites, mobile applications and online services you use.

We employ a number of technical, organizational and physical safeguards designed to protect the personal information we collect. However, security risk is inherent in all internet and information technologies and we cannot guarantee the security of your personal information.

We are headquartered in the United States and may use service providers that operate in other countries. Your personal information may be transferred to the United States or other locations where privacy laws may not be as protective as those in your state, province, or country.

Users in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the European Economic Area should read the important information provided below about transfer of personal information outside of the European Union.

The Service is not intended for use by anyone under 18 years of age. If you are a parent or guardian of a child from whom you believe we have collected personal information in a manner prohibited by law, please contact us. If we learn that we have collected personal information through the Service from a child without the consent of the child’s parent or guardian as required by law, we will comply with applicable legal requirements to delete the information.

We reserve the right to modify this Privacy Policy at any time. If we make material changes to this Privacy Policy, we will notify you by updating the date of this Privacy Policy and posting it on the Service or other appropriate means. Any modifications to this Privacy Policy will be effective upon our posting the modified version (or as otherwise indicated at the time of posting). In all cases, your use of the Service after the effective date of any modified Privacy Policy indicates your acknowledgment that the modified Privacy Policy applies to your interactions with the Service and our business.

Where this Notice to European users applies. The information provided in this “Notice to European users” section applies only to individuals located in the EEA or the UK (EEA and UK jurisdictions are together referred to as “Europe”).

Personal information. References to “personal information” in this Privacy Policy should be understood to include a reference to “personal data” (as defined in the GDPR) – i.e., information about individuals from which they are either directly identified or can be identified. It does not include “anonymous data” (i.e., information where the identity of individual has been permanently removed). The personal information that we collect from you is identified and described in greater detail in the section “Personal information we collect”.

Our legal bases for processing. In respect of each of the purposes for which we use your personal information, the GDPR requires us to ensure that we have a “legal basis” for that use.

We have set out below, in a table format, the legal bases we rely on in respect of the relevant Purposes for which we use your personal information – for more information on these Purposes and the data types involved, see How we use your personal information above.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retention. We retain personal information for as long as necessary to fulfill the purposes for which we collected it, including for the purposes of satisfying any legal, accounting, or reporting requirements, to establish or defend legal claims, or for compliance and protection purposes, unless specifically authorized to be retained longer.

To determine the appropriate retention period for personal information, we consider the amount, nature, and sensitivity of the personal information, the potential risk of harm from unauthorized use or disclosure of your personal information, the purposes for which we process your personal information and whether we can achieve those purposes through other means, and the applicable legal requirements.

When we no longer require the personal information, we have collected about you, we will either delete or anonymize it or, if this is not possible (for example, because your personal information has been stored in backup archives), then we will securely store your personal information and isolate it from any further processing until deletion is possible. If we anonymize your personal information (so that it can no longer be associated with you), we may use this information indefinitely without further notice to you.

Other information

No obligation to provide personal information. You do not have to provide personal information to us. However, where we need to process your personal information either to comply with applicable law or to deliver our Services to you, and you fail to provide that personal information when requested, we may not be able to provide some or all of our Services to you. We will notify you if this is the case at the time.

No Automated Decision-Making and Profiling. As part of the Services, we do not engage in automated decision-making and/or profiling, which produces legal or similarly significant effects. We will let you know if that changes by updating this Privacy Policy.

Security. We have put in place procedures designed to deal with breaches of personal information. In the event of such breaches, we have procedures in place to work with applicable regulators. In addition, in certain circumstances (including where we are legally required to do so), we may notify you of breaches affecting your personal information.

Your rights

General. European data protection laws give you certain rights regarding your personal information. If you are located in Europe, you may ask us to take any of the following actions in relation to your personal information that we hold:

Exercising These Rights. You may submit these requests by email. See the How to contact us section above for our contact details. We may request specific information from you to help us confirm your identity and process your request. Whether or not we are required to fulfill any request you make will depend on a number of factors (e.g., why and how we are processing your personal information), if we reject any request you may make (whether in whole or in part) we will let you know our grounds for doing so at the time, subject to any legal restrictions. Typically, you will not have to pay a fee to exercise your rights; however, we may charge a reasonable fee if your request is clearly unfounded, repetitive or excessive. We try to respond to all legitimate requests within a month. It may take us longer than a month if your request is particularly complex or if you have made a number of requests; in this case, we will notify you and keep you updated.

Your Right to Lodge a Complaint with your Supervisory Authority. In addition to your rights outlined above, if you are not satisfied with our response to a request you make, or how we process your personal information, you can make a complaint to the data protection regulator in your habitual place of residence.

The Information Commissioner’s Office

Water Lane, Wycliffe House

Wilmslow - Cheshire SK9 5AF

Tel. +44 303 123 1113

Website: https://ico.org.uk/make-a-complaint/

Data Processing outside Europe; we are a US-based company and many of our service providers, advisers, partners or other recipients of data are also based in the US. This means that, if you use the Services, your personal information will necessarily be accessed and processed in the US. It may also be provided to recipients in other countries outside Europe.

It is important to note that that the US is not the subject of an ‘adequacy decision’ under the GDPR – basically, this means that the US legal regime is not considered by relevant European bodies to provide an adequate level of protection for personal information, which is equivalent to that provided by relevant European laws.

Where we share your personal information with third parties who are based outside Europe, we try to ensure a similar degree of protection is afforded to it in accordance with applicable privacy laws by making sure one of the following mechanisms is implemented:

You may contact us if you want further information on the specific mechanism used by us when transferring your personal information out of Europe.

Este calendario es un obsequio para ti y para todes les 8000 integrantes de nuestra comunidad feminista global. Es nuestra promesa de conexión futura y de encuentro con los movimientos en el año próximo. Este año que pasó ha sido testigo de injusticias inenarrables. Damos la bienvenida a un nuevo año pleno de un potente espíritu de movimiento, de soluciones y estrategias esperanzadas. Por un mundo mejor para todes.

Cuando pases las páginas, nota la diversidad artística de nuestres integrantes artistas, que utilizan su obra para difundir e interconectar a nuestros distintos movimientos bajo el paraguas feminista. ¿Te ves a ti misme, a tu movimiento, a tus comunidades, en estas páginas? Te alentamos a utilizar este calendario como herramienta práctica para marcar el tiempo y el espacio, pero también para anotar las ocasiones de conectarte con feministas y activistas.

Related content

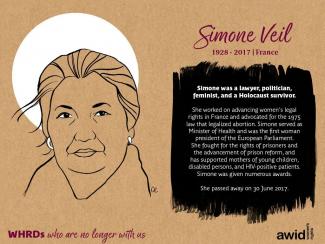

The Guardian: Simone Veil, Auschwitz survivor and abortion pioneer, dies aged 89

BBC: Simone Veil: French politician and Holocaust survivor dies

Reuters: French Holocaust survivor and pro-abortion campaigner Simone Veil dies at 89

¡Sí! En este momento el formulario requiere que se completen los nombres de lxs presentadorxs aun si no están confirmadxs todavía. Entendemos que es probable que se produzcan cambios durante el año.

Dans le cadre de notre engagement à nouer des liens plus profonds avec des artistes via nos pratiques de co-création de Réalités Féministes, AWID a collaboré avec un Groupe de Travail Artistique visant à faire progresser et à renforcer les programmes et réalités féministes, dans les communautés et mouvements via l’expression créative. Notre intention ici est de rassembler des féministes créatifs·ves dans un espace puissant et audacieux pour grandir et vivre librement, et briser les récits toxiques en les remplaçant par des alternatives transformatrices.

Cette exposition rassemblera le travail d’artistes et de collectifs du monde entier, de celle.ux qui créent activement la différence que nous voulons voir dans ce monde. Ces féministes créatifs·ves comprennent Upasana Agarwal, Nicole Barakat, Siphumeze Khundayi, Katia Herrera, Ali Chavez Leeds, Colectivo Morivivi, Ika Vantian, ainsi que les organisateurs·rices de l’exposition #MeToo en Chine. Leurs voix résonnent avec force dans leur refus d'accepter les limites imposées par le patriarcat, et amplifient leurs engagements envers les communautés dans lesquelles, et avec lesquelles, i.elles travaillent. Chaque œuvre représente, à sa façon, des actes de résistance quotidienne, des histoires et des identités inédites, des liens avec la terre et nos ancêtres et, plus important encore, la solidarité qui existe au sein et entre les mouvements et luttes féministes. Ces artistes inspirent et sont inspiré·e·s par des stratégies créatives de résistance et d'initiatives féministes qui nous montrent comment nous pouvons vivre ensemble dans un monde plus juste - un monde qui place au centre le soin et la guérison.

Les réalités féministes sont les exemples concrets des mondes justes que nous sommes en train de co-créer. Elles existent aujourd’hui, dans les manières, dont les personnes et les mouvements vivent, luttent et se construisent.

Ces réalités féministes vont au-delà de la résistance aux systèmes oppressifs pour nous montrer à quoi ressemble un monde sans domination, sans exploitation et sans suprématie.

Ce sont ces histoires-là que nous voulons mettre en lumière, partager et amplifier à travers notre aventures des réalités féministes.

Créer et élargir les alternatives: Ensemble, nous créons de l’art et des expressions artistiques qui placent au centre et célèbrent l’espoir, l’optimisme, la guérison et l’imagination radicale que les réalités féministes inspirent.

Enrichir nos connaissances: Nous documentos, démontrons & diffusons des méthodologies qui permettront d’identifier les réalités féministes de nos différentes communautés.

Promouvoir des programmes féministes: Nous élargissons et approfondissons notre réflexion et notre organization collectives afin de promouvoir des solutions et des systèmes justes incarnant les valeurs et les visions féministes.

Mobiliser des actions solidaires: Nous incitons les mouvements féministes, en faveur des droits humaines et de la justice de genre et leurs allié-e-s à partager, échanger et co-créer des réalités, des récits et des propositions féministes lors du 14ème Forum international de l’AWID.

Bien que nous mettions l’accent sur le processus avant, pendant et après les quatre jour du Forum, c’est lors de l’événement lui-même que la magie opère. Grâce à l’unique énergie des participant·e·s et à l’opportunité de rassembler les gens.

Construira le pouvoir des réalités féministes, en nommant, célébrant, amplifiant et en alimentant l’énergie autour des expériences et propositions qui font émerger les possibilités et nourrissent notre imagination

Remplira nos puits d’énergie et d’inspiration comme le carburant de notre activisme et de notre résilience pour les droits et la justice

Renforcera la connectivité, la réciprocité et la solidarité au sein des divers mouvements féministes et avec les mouvements en faveur des droits et de la justice.

En savoir plus sur le processus du Forum

لغات العمل في جمعية حقوق المرأة في التنمية هي الإنجليزية والفرنسية والإسبانية. ستتم إضافة اللغة التايلاندية كلغة محلية، بالإضافة إلى لغة الإشارة وإجراءات الاتصال الأخرى. يمكن إضافة لغات أخرى إذا سمح التمويل بذلك، لذا تحقق/ي مرة أخرى بانتظام للحصول على التحديثات. نحن نهتم بالعدالة اللغوية وسنحاول تضمين أكبر عدد ممكن من اللغات بقدر ما تسمح به مواردنا. نأمل في خلق فرص متعددة للكثيرين/ات منا للتواجد بلغاتنا والتواصل مع بعضنا البعض.

In collaboration with artist Naadira Patel, we created a scrapbook that highlights a handful of snapshots from AWID’s last four decades of feminist movement support.

Abby était une féministe pionnière, militante des droits humains.

Ancienne épidémiologiste de l'Université McGill, Abby était réputée pour défendre les causes sociales et pour ses critiques perspicaces concernant les technologies de procréation humaine assistée et d'autres sujets médicaux. Plus précisément, elle a fait campagne contre ce qu'elle a appelé la « généticisation » des technologies de procréation, contre l'hormonothérapie substitutive et pour des recherches plus qualitatives et plus longues avant l'approbation de nouveaux vaccins comme celui contre le papillomavirus humain.

À la nouvelle de son décès, ses ami-e-s et collègues l'ont décrite avec affection comme une « ardente défenseure » de la santé des femmes.

يرجى حساب تكاليف السفر إلى بانكوك، والإقامة والبدل اليومي، والتأشيرة، وأي احتياجات خاصة بإمكانية الوصول، والنفقات الطارئة، بالإضافة إلى رسوم التسجيل التي سيتم الإعلان عنها قريبًا. تتراوح أسعار الفنادق في منطقة سوكومفيت في بانكوك ما بين 50 دولارًا أمريكيًا إلى 200 دولار أمريكي في الليلة الواحدة في حالة حجز غرفة مزدوجة.

يحصل أعضاء جمعية حقوق المرأة في التنمية على خصم عند التسجيل، لذلك إذا لم تكن عضوًا/ة بعد، فإننا ندعوك إلى التفكير في أن تصبح عضوًا/ة والانضمام إلى مجتمعنا النسوي العالمي.

AWID, el Center for Women’s Global Leadership [CWGL, Centro por el Liderazgo Global de las Mujeres], y la African Women's Development and Communication Network [FEMNET, Red de Desarrollo y Comunicación de las Mujeres Africanas], presentan esta plataforma como aporte para cuestionar las nociones dominantes acerca del desarrollo y poner sobre la mesa propuestas iniciales para una agenda feminista para el desarrollo y la justicia económica y de género.

¿Cómo se originó este proyecto?

Estas propuestas son exactamente eso: se ideas y experiencias a ser conversadas, debatidas, para que les sumemos elementos, las desmenucemos, las adaptemos, las adoptemos e incluso para que inspiren otras propuestas.

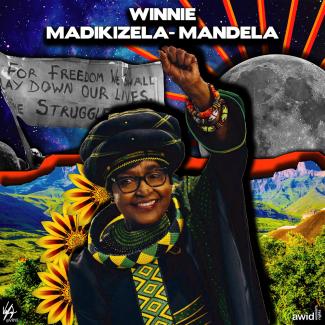

Winnie has been described as a “militant firebrand activist” who fought the apartheid regime in South Africa.

She was imprisoned multiple times, and on many occasions placed in solitary confinement.

Ma’Winnie, as she is affectionately remembered, was known for being outspoken about the challenges Black women faced during and after apartheid, having been on the receiving end of these brutalities herself as a mother, wife and activist during the struggle. She transcended the misconception that leadership is gender, class or race-based. Despite being a controversial figure, she is remembered by many by her Xhosa name, “ Nomzamo”, which means "She who endures trials".

Ma’Winnie continues to be an inspiration to many, particularly young South African women for whom her death has spurred a burgeoning movement, with the mantra: "She didn't die, she multiplied."