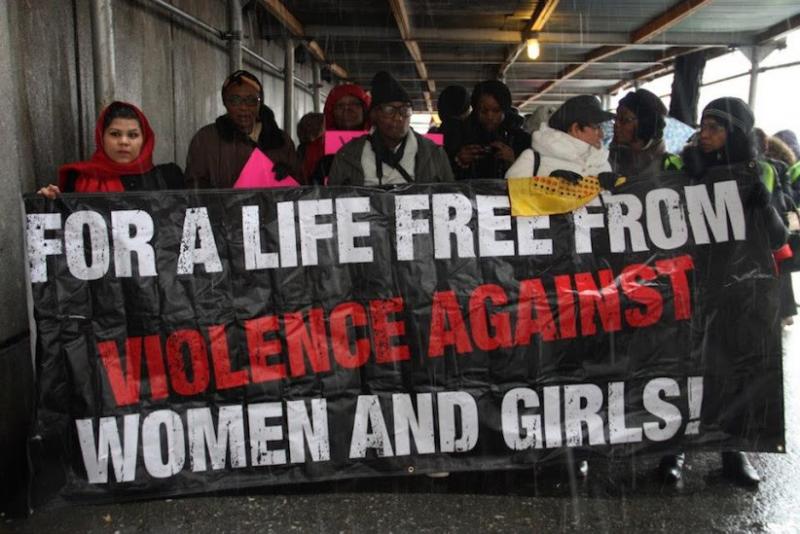

FRIDAY FILE - The Commission on the Status of Women (CSW 57) ended last week Friday with an Agreed Conclusions document acknowledged by many as fair and balanced, and “an important step forward” to addressing violence against women and girls (VAWG).

Following the annual two-week long meeting at the United Nations (UN) Headquarters in New York under the theme the Elimination and prevention of all forms of violence against women and girls (VAWG), UN officials and activists celebrated the news that the CSW57 would end with Agreed Conclusions (AC). The majority of States accepted the overall text and commended it as ‘fair and balanced’. However, on both ends of the political spectrum, States expressed some disappointment with the text, some regretting that more progress was not made, and others such as Egypt, Libya, Jordan, Iran, Qatar, the Vatican (Holy See), Nicaragua, Honduras and Sudan expressing reservations with parts of the text especially those which made explicit references to sexual rights and reproductive rights.

But, in 2013, when we should be advancing rights that were hard fought for and agreed to almost two decades ago; and implementing programmes to expedite women’s access to and realisation of these rights, including those laid out in a range of international agreements[2], women’s rights activists spent two hard weeks pushing back against fundamentalist opposition attempting to roll back women’s human rights.

Strong fundamentalist opposition

In our first Friday File we questioned whether we would see real progress and political commitment by States in addressing violence against women and girls (VAWG). This year’s Agreed Conclusions were the result of flexibility and compromise, necessary to avert a similar situation to last year’s CSW 56 that failed to adopt agreed conclusions, largely due to polarisation of positions because of strong fundamentalist opposition by a small group of conservative countries.

These groups were in full force and stronger this year, in “unholy alliances”, including diverse States such as Iran, Russia, Syria, Egypt, some States in the African group and the Vatican, who were united in positions against women’s sexual and reproductive rights, and rights of those who are violated because of their sexual orientation and gender identities (SOGI). These States obstructed the negotiations and lobbied hard to water down language that was agreed to decades ago.

Midway into the second week of negotiations Egypt’s ruling Muslim Brotherhood, lambasted the proposed CSW outcome document, saying that the document, which calls for an end to VAWG, will “lead to complete disintegration of society… eliminating the moral specificity that helps preserve cohesion of Islamic societies”.

In the 10 point statement the Muslim Brotherhood objected to granting women sexual freedom, sexual and reproductive rights, equal rights for ‘homosexuals’, respect and protection for ‘prostitutes’, equal rights for children born out of wedlock, the equal rights of women, in marriage, inheritance, sharing family roles and the right of women to lay charges of rape against their husbands. The Arab caucus at the CSW - women’s and human rights groups - from Egypt, Lebanon, the Palestinian territories, Jordan and Tunisia expressed concern and opposition to the statement, and urged governments “to clearly denounce all practices which perpetuate violence against women and girls, including those which are justified on the basis of tradition, culture and religion, and work on eliminating them.”

Feminist and women’s organisations issued a statement raising concerns about “the very alarming trends in the negotiations of outcome document of the 57th session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women”, calling on governments to say “NO to any re-opening of negotiations on the already established international agreements…commend those states that are upholding women’s rights in totality ... and reject any attempt to invoke traditional values or morals to infringe upon human rights guaranteed by international law”.

Advances in addressing VAWG

Women human rights defenders (WHRDs)

One of the major coup’s for WHRDs at this year’s CSW is the inclusion, for the first time ever, of language in the Agreed Conclusions that specifically requires States to “Support and protect those who are committed to eliminating violence against women, including women human rights defenders in this regard, who face particular risks of violence.” WHRDs are not a specific sub-group advocating for one specific issue, rather they are active in advocating for the realization of all human rights.

The tireless work, both before and during the CSW, by members of the Women Human Rights Defender International Coalition (WHRD IC) and allies who advocated with member States to include strong language in the ACs paid off for WHRDs, but did not come without resistance. Several states, including Iran, China, Cuba, Syria and a few African States[3], failed to acknowledge that violence against WHRDs is directly linked to their gender and the work they do to protect women’s rights including gender-based violence, sexual and reproductive rights and violence based on SOGI.

The initial drafts of the ACs included three references to WHRDs, but when it came down to last minute negotiations, champions of WHRDs including Mexico, Colombia, Turkey and the EU had to compromise significant parts of the text to ensure that WHRDs were reflected in the final ACs. Members of WHRD IC welcome the recognition of WHRDs in the ACs but also note that it could be stronger and should include commitments to ensure WHRDs can carry out their work in defence of human rights without fear of reprisals, coercion, intimidation or any such attacks.

Sexual rights and reproductive rights and health

Sexual rights and reproductive rights and health organizations and activists worked hard to ensure that gains from previous agreements[4] were not rolled back and fought hard for the explicit reaffirmation of accessible and affordable health care services, including sexual and reproductive health services such as emergency contraception and safe abortion, for survivors of violence and urged governments, for the first time, to procure and supply female condoms. The link between HIV and VAWG is a recurring theme throughout the ACs, with governments committing to strengthen and coordinate programmes and services addressing the intersection between HIV and VAWG as well as recognizing the need to focus services on the diverse experiences of women and girls.

Governments made specific commitments to ensure safety of girls in public and private spaces as well as commitment to end early and forced marriage. They also committed to preventing, investigating, and punishing acts of violence committed by people in positions of authority, such as teachers, religious leaders, political leaders and law enforcement officials. Other important gains include reaffirming comprehensive evidence-based sexuality education as a means tackle social and cultural patterns of conduct of men and women, promote gender equality and eliminate prejudice.

The ACs reaffirm that States should “strongly condemn all forms of violence against women and girls and to refrain from invoking any custom, tradition or religious consideration to avoid their obligations with respect to its elimination as set out in the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women.” The retention of “religious” in the first paragraph and the inclusion of “religious leaders” were hard fought for by progressive States.

Some of the obstacles

What was clear from the fortnight of negotiations is that conservative States are not ready to accept and advance rights related to SOGI. There was continual reinforcement of traditional normative relationships in the language of the ACs and complete refusal to acknowledge, and therefore erasure, of groups that do not conform to traditional gender identities and roles or within a traditional patriarchal construct. While there is growing consensus and support regarding the need to include explicit language related to specific groups that face particular forms of violence, including lesbian, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LBTI) women, no agreement could be reached on this language, with conservative States blocking language that highlights the violence women and girls experience in the diversity of relationships they engage in. References to intersectionality as a basic concept for understanding how the multiple forms of discrimination women and girls face are inextricably linked to factors such as race, ethnicity, religion, health ability, status, age, class and caste were also absent from the final outcome document.

States also failed to reach consensus on the role of families in combating VAWG as conservative governments and the Vatican would not recognize that diverse forms of families exist. The backward statement that the “traditional family” must be protected was met with heavy criticism from several progressive governments that resulted in the paragraph being deleted from the ACs.

There was strong opposition to language suggesting that rape includes forced behaviour by a woman’s husband or intimate partner. Although some States strived to retain intimate partner violence, a term that more adequately captures the range of relationships and spaces where violence and abuse take place, in the end, it was left out of the ACs.

Also disappointing was the lack of support for the proposal by Brazil to apply measures for combating violence against sex workers. Given that the CSW was discussing prevention and elimination of VAW, the failure to recognize sex workers as a vulnerable group is a huge loss. Disappointingly several governments took the opportunity to call for the elimination of demand for prostitution and/or to conflate sex work with trafficking; and worse yet to promote the simplistic view that the proposal was encouraging women to engage in prostitution.

What does this mean for women’s human rights as we move towards 2015?

Over 190 country delegations and 6000 representatives from civil society attended this year’s CSW with strong acknowledgement by government delegations of the critical role played by civil society, who were described as “fierce and hard working”.

Shareen Gokal of AWID, believes that this year’s CSW helped strengthen the women’s rights movement because it provided an opportunity for women’s rights organisations and activists to share experiences multi-generationally, across boundaries, countries, sectors and issues. It provided an opportunity for rich exchanges and learnings between those activists more experienced in the space and those newer to it. The diversity of the space brought a range of experiences for advocates who traversed the political spectrum from working with ally States to advance negotiations; to coming up against strong opposition, providing an opportunity to monitor the types of arguments and tactics being used and where possible, to counter and challenge these with rights-based perspectives.

While feminists and women’s rights advocates agree that they did not get all the language they had hoped for, they welcome the CSW57 Agreed Conclusions as an achievement and the result of a lot of hard work and determination despite the very strong fundamentalist backlash. This will certainly bode well as women’s rights advocates continue their work to influence the Post 2015 Development Agenda[5], and ensure that VAWG is a priority for the achievement of sustainable development, peace and security, human rights, economic growth and social cohesion.

AWID will publish additional Friday Files related to the CSW in the coming weeks, looking into key dynamics and issues at stake and key learnings for future CSW meetings and other intergovernmental processes.

[1] The author thanks Lydia Alpízar Durán, Marisa Viana and Shareen Gokal for their contributions to the article.

[2] Including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA), International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action, Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women(CEDAW), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women.

[3] Namely Nigeria and Cameroon.

[4] The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and in the Programme of Action at the International Conference on Population and Development and the Key Actions for its Further implementation.

[5] See AWIDs Friday Files: The Post 2015 Development Agenda – What it Means and How to Get Involved and The UN Post-2015 Development Agenda – A Critical Analysis