From the 10th-12th of April 2016, the fourth African Feminist Forum will take place in Zimbabwe, bringing together a range of wisdom, experience and insight from feminist organisers and activists from across the continent.

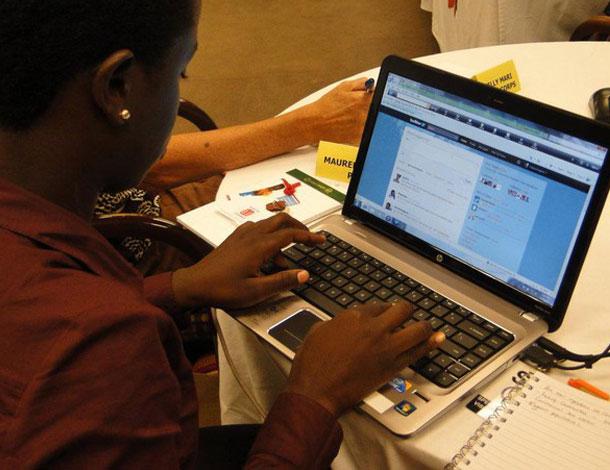

Undoubtedly, and in a bigger way than has been experienced with previous African feminist forums, digital technologies will play a significant role in the dynamics of this event.

For while many – especially those attending the Forum from beyond Zimbabwe - may not have met physically before, they probably will have interacted online as a result of the increasing ubiquity of digital technologies; and social media in particular. In 2007, Oreoluwa Somolu[1] wrote a paper on African women's storytelling for social change, and in it she stated of blogging that

“... Its true potency lies in its ability to give a voice to the previously unheard, and provide them with the tools to connect with others who share the same concerns... providing them with a platform on which they can map a strategy for raising the quality of women's lives in Africa.”

Having gathered around hashtags and social media campaigns like #BringBackOurGirls and #AfriFem, many feminist organisers of the global south – and globally – have come to know and nurture each other in the new ways that the online realm provides.

But while this gives revolutionary power to the collective cause of social justice, there are still many structural and socio-political issues to consider within our online movement building.

In the introduction to the 'ICTs for Feminist Movement Building Activist Toolkit' produced by JASS, APC and Women's Net, feminist communication strategies that use ICTs are explained as being essential to building movements that are “… effective, resilient, visible and safe”. As I unpacked this topic further, I thought more deeply around these ideas so as to imagine what such movements might look like.

Effectiveness

Firstly, to be effective, movements making the use of digital technologies must be practical. In other words, they must meet feminists at their point of need, and be able to offer something of meaning to their plights and causes. So what does this look like, practically?

In 2012, I founded an online platform called Her Zimbabwe, which crowd-sources opinion and analysis from young feminists in Zimbabwe and Africa.

The idea is to give these young women a space to express themselves, meeting what is commonly referred to as strategic needs; needs rooted in rights and expression. But at the same time, their practical needs are something that we are invested in. In other words, the reality of their need to pay for access to the internet coupled with a structural analysis of their relative social standing (formal employment rates in Zimbabwe are often quoted as being just over 10%, while at the same time, young women remain almost invisible as producers of knowledge in the mainstream media) means that we appreciate that participation for many young women entails real financial impediments.

This is why we offer our writers, along with interactive feminist editorial support, a modest payment for content that we publish. And over time, we've seen first hand how such support has enabled young women to invest further into cultivating their online presence (either through paying towards their data costs or purchasing equipment like laptops or smartphones).

In order to be effective, our online feminist movement building has to be inclusive, with inclusion entailing a constant analysis of who has access, and therefore who is listened to. To take another example, if we imagine an inclusive multi-generational movement, what barriers and opportunities (for listening, reflection and intergenerational historicisation) do digital technologies present to women of different technological eras? There is certainly more need to build women's digital literacy capacity and confidence, and address their practical concerns, in order to make our movements more robust, and therefore effective.

Resilience and visibility

Secondly, how can digital technologies make our movements more resilient?

I think here of resilience like recovery from a terrible cold; the type of opportunistic sickness that has you believing that you will never be well again. And yet somehow, over time, the medicine you take and the self-care you invest in rebuilds your body's defense systems so that it can heal itself. How can digital technologies act as healing for the pain and trauma that comes with our work of organising? How can they infuse our movement's immunity with the antigens that reinvigorate our struggles?

There are many ways.

One is that in times of great proscription or danger of offline organising, online spaces allow us a virtual meeting point to vent, cry, celebrate, and re-energise. New solidarities are formed and old ones are reinforced. A recent case in point is the murder of Honduran environmental activist, Berta Caceres (with the Twitter hashtag #BertaCaceres still in use over a month since her assassination) whose fight for indigenous land rights has prompted important conversations around state and corporate power, and women's bodies as sites of its brutal perpetuation.

Oftentimes, resilience is built by knowing that we are not alone in the fight and through the acknowledgement of those whose sacrifices are sometimes more than we can even fathom. It is such intersectionalities that make ourselves – and our movements – stronger, replenishing us on our long struggle.

Making our movements more visible is probably a more obvious function of digital technologies.

Feminist issues become less localised, less geolocated, and more global and diverse, as people can engage and participate in a more decentralised manner than physical interaction allows and inhibits. Through our collective use of video, audio and text through platforms as diverse as YouTube, Facebook and Whatsapp we are making the work of our movements more readily archivable, more searchable, and more accessible.

Safety

The final issue to consider is how digital technologies can make our movements safer.

At face value, this sounds contradictory. For we know, from reports like that recently released by the United Nations Broadband Commission - titled 'Cyber Violence Against Women and Girls' – that almost 75% of women have endured cyber violence, and that women are 27 times more likely than men to be harassed online. We also know that in some contexts, and as a result of socialisation into entrenched invisibility or as a function of broader political censorship, feminists can only use closed networks of communication (eg. SMS or private chat, with encryption sometimes) with people they know and trust as open channels lay them open to ostracism and violence.

To make our movements safer, we have to temper our desire for visibility with that of women's practical needs. This means having public spaces, where this makes sense, and private spaces where feminists may feel safer to more fully articulate certain issues.

It also means supporting anonymity and assumed identities, especially in circumstances where certain identities (eg. LGTBQI and/ or disabilities) and experiences (eg. rape and/ or abortion) are either socially maligned or marginalised. And it also means investing time and thought into making our public spaces safer and having strategies for dealing more effectively and coordinately with trolls and other perpetrators of cyber violence.

The Feminist Principles of the Internet note that surveillance, by its very nature, is a tool of patriarchal control and restriction and that our right to privacy is essential for a more open Internet. As such, part of our work in making our movements safer is to engage at the more strategic policy level with state actors, civil society and digital technology corporations to assert our rights to safe and feminist spaces.

However, there are still many questions to be discussed and answered.

Who owns the platforms we use and how do they really work? Who owns our content and how do we use online spaces consciously? How do we get conversations that are not happening online into digital spaces, and how do we get online conversations offline, all while remaining acutely aware of the delicate line between allyship and 'speaking on behalf of'? Who is archiving our online sharing? Who is making sense of all this magic happening in a time when physical distance yields to digital immediacy? How do we organise our online presences into new knowledge? How do we teach and share these?

There is a danger to our organising if we do not also become more reflective of all these questions and many more. There is also a danger if we do not reflect more constantly on power, for we must remain critical of it, both internally and externally. Who owns the spaces we claim? And which of us gets to speak within them?

It is only through continuous introspection and regeneration that we can truly build an effective, resilient and safer 'us' online that is both responsive and responsible.

About the author

Fungai Machirori is a Zimbabwean feminist researcher, commentator and blogger. In 2012, she founded Her Zimbabwe, a feminist web-based platform for young women.

[1] Somolu. O. (2007). 'Telling Our Own Stories': African Women Blogging for Social Change. Gender and Development 15 (3): 477-89.