Natalia Estemirova

WHRDs are self-identified women and lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LBTQI) people and others who defend rights and are subject to gender-specific risks and threats due to their human rights work and/or as a direct consequence of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

WHRDs are subject to systematic violence and discrimination due to their identities and unyielding struggles for rights, equality and justice.

The WHRD Program collaborates with international and regional partners as well as the AWID membership to raise awareness about these risks and threats, advocate for feminist and holistic measures of protection and safety, and actively promote a culture of self-care and collective well being in our movements.

WHRDs are exposed to the same types of risks that all other defenders who defend human rights, communities, and the environment face. However, they are also exposed to gender-based violence and gender-specific risks because they challenge existing gender norms within their communities and societies.

We work collaboratively with international and regional networks and our membership

We aim to contribute to a safer world for WHRDs, their families and communities. We believe that action for rights and justice should not put WHRDs at risk; it should be appreciated and celebrated.

Promoting collaboration and coordination among human rights and women’s rights organizations at the international level to strengthen responses concerning safety and wellbeing of WHRDs.

Supporting regional networks of WHRDs and their organizations, such as the Mesoamerican Initiative for WHRDs and the WHRD Middle East and North Africa Coalition, in promoting and strengthening collective action for protection - emphasizing the establishment of solidarity and protection networks, the promotion of self-care, and advocacy and mobilization for the safety of WHRDs;

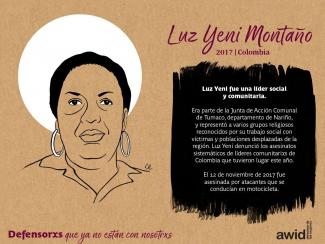

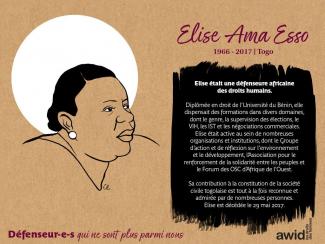

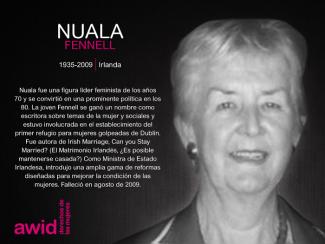

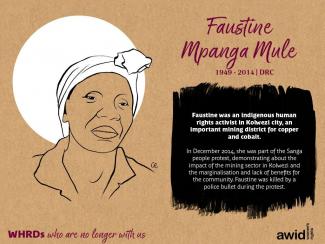

Increasing the visibility and recognition of WHRDs and their struggles, as well as the risks that they encounter by documenting the attacks that they face, and researching, producing, and disseminating information on their struggles, strategies, and challenges:

Mobilizing urgent responses of international solidarity for WHRDs at risk through our international and regional networks, and our active membership.

La economía solidaria (que incluye la economía cooperativa y la llamada economía del don) es un marco alternativo que adquiere formas diferentes según el contexto y está siempre abierto a los cambios.

Este marco de referencia se asienta sobre los siguientes principios:

En una economía solidaria, quienes producen participan en procesos económicos que guardan íntima relación con sus realidades, con la preservación del medio ambiente y la cooperación mutua.

Según la geógrafa feminista Yvonne Underhill-Sem, la economía del don es un sistema económico en el que los bienes y servicios circulan entre las personas sin que haya acuerdos explícitos acerca de su valor o de una reciprocidad esperada en el futuro.

Lo que hay detrás del otorgamiento de dones es una relación humana, una generación de buena voluntad y el acto de prestar atención a nutrir a toda la sociedad y no solo a lo que concierne a unx mismx y su familia: se trata del colectivo.

En el Pacífico, por ejemplo, esto se manifiesta en la recolección, preparación y procesamiento de recursos terrestres y marinos para tejer alfombras, abanicos, guirnaldas y objetos ceremoniales, así como en la cría de ganado y el almacenamiento de las cosechas estacionales.

Las mujeres tienen diversos incentivos para involucrarse en actividades económicas y que van desde satisfacer sus aspiraciones profesionales y ganar dinero para gozar de una vida confortable en el largo plazo hasta llegar a fin de mes, pagar deudas y huir del desgaste de una vida rutinaria.

Para acomodarse a los diferentes ambientes en los que operan las mujeres, el concepto de economía solidaria está en permanente desarrollo, discusión y debate.

La Coopérative Textile Nadia Echazú porte le nom d'une pionnière dans la lutte pour les droits des personnes trans en Argentine. À bien des égards, le travail de la coopérative célèbre la vie et l'héritage de Nadia Echazú, qui a eu une carrière militante remarquable.

La Coopérative Textile Nadia Echazú porte le nom d'une pionnière dans la lutte pour les droits des personnes trans en Argentine. À bien des égards, le travail de la coopérative célèbre la vie et l'héritage de Nadia Echazú, qui a eu une carrière militante remarquable.

Peu de temps après sa mort, ses collègues militantes ont fondé la coopérative en son nom, pour honorer la marque profonde qu'elle a laissée sur l'activisme trans et travesti en Argentine.

AWID agradece a las numerosas personas cuyos análisis, ideas y contribuciones han dado forma a la investigación y las acciones de promoción de "¿Dónde está el dinero para las organizaciones feministas?" a lo largo de los años.

Ante todo, vaya nuestro agradecimiento más profundo a lxs afiliadxs y activistas de AWID que participaron en las consultas de ¿Dónde está el dinero? y ensayaron esta encuesta con nosotrxs, y que compartieron su tiempo, sus análisis y el corazón con tanta generosidad.

Expresamos nuestra gratitud a los movimientos, aliados y fondos feministas, entre otros, a Black Feminist Fund, Pacific Feminist Fund, ASTRAEA Lesbian Foundation for Justice, FRIDA Young Feminist Fund, Purposeful, Kosovo Women’s Network, Human Rights Funders Network, Dalan Fund y PROSPERA por su rigurosa investigación sobre el estado de la dotación de recursos, sus agudos análisis y promoción sostenida para más y mejor financiamiento y poder para las organizaciones feministas y por la justicia de género en todos los contextos.

La crise économique mondiale actuelle fournit la preuve évidente que les politiques économiques des trois dernières décennies n’ont pas fonctionné.

La dévastation que la crise a opéré sur les ménages les plus vulnérables dans les pays du Nord et du Sud nous rappelle que la formulation de politiques économiques et la réalisation des droits humains (économiques, sociaux, politiques, civils et culturels) ont été trop longtemps séparées l’une de l'autre. La politique économique et les droits humains ne doivent pas être des forces opposées, elles peuvent coexister en symbiose.

Les politiques macroéconomiques influencent le fonctionnement de l'économie dans son ensemble, elles façonnent la disponibilité et la distribution des ressources. Dans ce contexte, les politiques budgétaires et monétaires sont fondamentales.

La politique budgétaire se réfère à la fois aux recettes et aux dépenses publiques, et aux relations entre elles qui sont formulées dans le budget de l’État.

La politique monétaire regroupe les politiques sur les intérêts et les taux de change et la masse monétaire, ainsi que la réglementation du secteur financier.

Les politiques macroéconomiques sont mises en œuvre à l’aide d'instruments tels la fiscalité, les dépenses du gouvernement, et le contrôle entre la masse monétaire et le crédit.

Ces politiques affectent les taux d’intérêt et les taux de change qui ont une influence directe sur, entre autres choses, le niveau de l'emploi, l'accès à un crédit abordable et le marché du logement.

L'application d'un cadre de droits humains aux politiques macroéconomiques permet aux États de mieux se conformer à leur obligation de respecter, de protéger et de réaliser les droits économiques et sociaux. Les droits humains sont inscrits aux conventions internationales selon des normes universelles. Ces normes juridiques sont énoncées dans les traités des Nations Unies tels la Déclaration universelle des droits de l'homme (DUDH), le Pacte international relatif aux droits civils et politiques (PIDCP) et le Pacte international relatif aux droits économiques, sociaux et culturels (PIDESC).

L’Article 1 de la DUDH stipule que « Tous les êtres humains naissent libres et égaux en dignité et en droits ».

Bien que la DUDH ait été rédigée il y a près de six décennies, sa pertinence est toujours de mise. La plupart des principes énoncés répondent aux problèmes auxquels les gens continuent d’être confrontés à l'échelle mondiale. Les questions concernant les châtiments inhumains (art. 5), la discrimination (art. 7), la propriété (art. 17), un salaire égal pour un travail égal (art. 23/2), et l'accès à l'éducation (art. 26/1) sont des questions pertinentes tant pour les pays au Sud et au Nord de l'équateur.

En particulier, les États ont l'obligation, en vertu du droit international, de respecter, de protéger et de réaliser les droits humains, y compris les droits économiques et sociaux des personnes relevant de leur compétence. Cet aspect est particulièrement pertinent aujourd'hui, compte tenu de la crise financière. Aux États-Unis, la réglementation est faussée en faveur de certains intérêts. Dans le contexte du changement social et économique actuel, l'incapacité des gouvernements à étendre leur rôle de surveillance est un échec cuisant face à l’obligation de protéger les droits humains.

Les États devraient respecter les principes clés des droits humains pour réaliser les droits économiques et sociaux. Certains de ces principes ont des implications potentiellement importantes pour la gouvernance des institutions financières et des marchés. Ces possibilités ont été sous explorées jusqu’à présent.

Les droits économiques et sociaux ont un ancrage institutionnel et juridique concret. Les traités internationaux, les déclarations mondiales, les conventions, et, dans un certain nombre de cas, les constitutions nationales ont intégré certains aspects des cadres de droits économiques et sociaux, ce qui a permis l’élaboration d’infrastructures institutionnelles au niveau du droit national et international.

Certaines personnes avancent que l’idée d’une justice mondiale n’est peut-être pas un exercice utile en raison des complexités institutionnelles en jeu. Toutefois, les institutions mondiales ont sans aucun doute des incidences sur la justice sociale, à la fois positives et négatives.

Il est utile de déterminer ce que ces éléments des cadres alternatifs impliquent pour la gouvernance économique, en particulier ceux qui sont soutenus par les institutions existantes. Le cadre des droits économiques et sociaux est un bon exemple concret : ce cadre évolue constamment et les discussions et les délibérations en cours sont nécessaires afin d'aborder les sections sous développées et les lacunes potentielles.

Cette section est fondée sur le blog du CWGL intitulé Applying a Human Rights Framework to Macroeconomic Policies (L'application d'un cadre de droits humains aux politiques macroéconomiques, 2012).

Absolutamente; deseamos saber de ustedes y su experiencia con la obtención de recursos.

Les acteurs anti-droits ont eu un impact substantiel sur le cadre relatif aux droits humains et sur l’interprétation progressiste des normes relatives à ces droits, en particulier dans le champ du genre et de la sexualité.

Pour mesurer l’impact de l’action des conservateurs dans les espaces politiques internationaux, il suffit de constater l’immobilisme et les régressions qui caractérisent la situation actuelle.

Nous sommes témoins de l’affaiblissement des accords et des engagements existants ; de négociations dans l’impasse ; du travail de sape continu mené à l’encontre des agences des Nations Unies, des organes de surveillance des traités et des Procédures spéciales ; et enfin de l’intégration d’un langage rétrograde dans les documents internationaux relatifs aux droits humains.

La CSW, qui se réunit chaque année en mars, est depuis longtemps l’un des espaces les plus contestés du système des Nations Unies. En mars 2015, les conservateurs ont donné le ton avant même que les événements ou les négociations ne commencent. Le document final élaboré par la Commission s’est avéré être une Déclaration très peu ambitieuse qui avait été négociée avant même que les activistes des droits des femmes n’aient pu intervenir.

Pendant la CSW 2016, le nouveau Caucus des jeunes a été infiltré par un grand nombre d’activistes anti-avortement et anti-droits sexuels et reproductifs qui ont réussi à réduire les organisations de jeunes progressistes au silence. Une fois de plus, les intenses négociations ont abouti à un texte terne dans lequel les éléments relatifs à « la famille » sont formulés dans un langage rétrograde.

Alors qu’il est devenu particulièrement important et urgent de faire progresser les droits humains des femmes, la CSW est devenue un espace affaibli et dépolitisé. Il est de plus en plus difficile d’envisager d’y faire progresser ces droits dans la mesure où les activistes progressistes utilisent toute leur énergie pour essayer de faire barrage au recul voulu par les conservateurs.

En tant qu’organe intergouvernemental responsable de la promotion et de la protection des droits humains dans le monde entier, le CDH est une porte d’entrée essentielle pour les conservateurs. Ces dernières années, cette institution a été le théâtre d’un certain nombre de démarches anti-droits.

En concertation avec d’autres acteurs anti-droits, certains États et blocs d’États conservateurs ont adopté une stratégie qui vise à faire retirer tout langage progressiste des résolutions et à introduire des amendements hostiles. Ils s’attaquent le plus souvent aux résolutions qui traitent de droits relatifs au genre et à la sexualité.

Par exemple, lors de la session du CDH qui s’est tenue en juin 2016, les États membres de l’Organisation de coopération islamique (OCI) et leurs alliés se sont opposés à l’adoption d’une résolution sur la discrimination à l’égard des femmes. Au cours de négociations tendues, de multiples dispositions ont été supprimées, y compris celles relative au droit des femmes et des filles de contrôler leur sexualité et leur santé ainsi qu’à leurs droits sexuels et reproductifs. Ont également été supprimées toutes les dispositions portant sur la nécessité d’abroger les lois qui perpétuent l’oppression patriarcale des femmes et des filles dans les familles et celles qui criminalisent l’adultère ou pardonnent le viol conjugal.

Le CDH a également été le théâtre d’initiatives pernicieuses des conservateurs visant à coopter les normes relatives aux droits humains et à introduire un langage conservateur en matière de « droits humains » – comme celui utilisé dans les résolutions en faveur des « valeurs traditionnelles » soutenues par la Russie et ses alliés et, plus récemment, dans le cadre de la campagne pour la « protection de la famille ».

En 2015, un certain nombre d’organisations religieuses conservatrices ont ouvert un nouveau front de lutte en commençant à s’attaquer à la Commission des droits de l’homme, organe de contrôle de l’application du Pacte international relatif aux droits civils et politiques (PIDCP) et instrument essentiel pour les droits humains.

Des groupes anti-droits se sont mobilisés dans l’espoir de faire inclure leur rhétorique anti-avortement dans le traité.

Lorsque la Commission a annoncé qu’elle rédigeait une nouvelle interprétation autorisée du droit à la vie, plus de 30 acteurs non étatiques conservateurs ont envoyé des observations écrites, avançant leurs arguments fallacieux sur le « droit à la vie » – à savoir que la vie commence dès la conception et que l’avortement est une violation de ce droit. Ils ont demandé à ce que ces idées soient incorporées dans l’interprétation de l’article 6 par la Commission.

L’action concertée de ces groupes conservateurs auprès de la Commission des droits de l’homme représente une évolution notable dans la mesure où elle concrétise la volonté des acteurs anti-droits de saper et d’invalider le travail essentiel qu’accomplissent les organes de surveillance de l’application des traités, dont celui de la Commission des droits de l’homme elle-même.

En 2015, les acteurs anti-droits ont mené des actions de plaidoyer dans le cadre de l’élaboration des nouveaux objectifs de développement durable (ODD), insistant une nouvelle fois sur les droits relatifs au genre et à la sexualité. Leurs efforts pour faire adopter un langage rétrograde dans le Programme de développement durable à l’horizon 2030 ont été moins fructueux.

Néanmoins, après avoir réussi à empêcher l’inclusion d’un langage progressiste dans le texte final, les conservateurs ont ensuite adopté une autre stratégie. Pour minimiser la responsabilité des États et saper l’universalité des droits, plusieurs États ont émis de multiples réserves sur les ODD.

Au nom du Groupe des États africains membres de l’ONU, le Sénégal a affirmé que les États africains ne « mettraient en œuvre que les ODD alignés sur les valeurs culturelles et religieuses de ses pays membres ».

Le Saint-Siège a également émis un certain nombre de réserves, affirmant qu’il était « certain que l’engagement selon lequel ‘personne ne serait laissé de côté’ serait compris comme une reconnaissance du droit à la vie de la personne, de la conception jusqu’à la mort naturelle ».

L’Arabie saoudite est allée plus loin encore, déclarant que le pays ne suivrait pas les règles internationales relatives aux ODD qui feraient référence à l’orientation sexuelle ou à l’identité de genre, les qualifiant de « contraires à la loi islamique ».

Les acteurs anti-droits ont un pouvoir d’influence de plus en plus marqué au sein de l’Assemblée générale des Nations Unies. En 2016, lors de la 71e session, l’AG a été le théâtre de la féroce opposition des acteurs anti-droits à un nouveau mandat créé en juin 2016 en vertu de la Résolution du Conseil des droits de l’homme sur l’orientation sexuelle et l’identité de genre : le mandat d’Expert indépendant pour la protection contre la violence et la discrimination basées sur l’orientation sexuelle et l’identité de genre[Béné1] (OSIG). Quatre actions ont été mises en œuvre dans les espaces de l’AG pour tenter de réduire la portée de ce mandat.

Le Groupe des États africains a notamment coordonné la présentation d’une résolution hostile auprès de la Troisième Commission[Béné2] , visant essentiellement à faire indéfiniment ajourner ce nouveau mandat. Bien que cette tentative n’ait pas abouti, il s’agit d’une tactique nouvelle et préoccupante visant à bloquer rétroactivement la création d’un mandat présenté par le Conseil des droits de l’homme.

Les acteurs anti-droits œuvrent maintenant à porter directement atteinte à l’autorité du CDH auprès de l’Assemblée générale. Les acteurs anti-droits ont également tenté de nuire à ce mandat en menant une actions auprès de la Cinquième Commission (chargée des questions administratives et budgétaires). Cette initiative inédite a conduit un certain nombre d’États à tenter (encore une fois sans succès) de bloquer le financement des experts des droits humains de l’ONU, dont celui de l’Expert indépendant pour la protection contre la violence et la discrimination basées sur l’orientation sexuelle et l’identité de genre.

Bien que ces multiples tentatives n’aient pas réussi à empêcher la création et le maintien de ce nouveau mandat, le soutien important que ces acteurs ont reçu, les stratégies innovantes qui ont été mise en œuvre et les puissantes alliances régionales qui se sont forgées tout au long des négociations nous donnent une idée des difficultés auxquelles nous allons devoir faire face.

Télécharger le chapitre complet (en anglais)

Le financement extérieur inclut les subventions et autres formes de financement de la part de fondations philanthropiques, de gouvernements, de financeurs bilatéraux, multilatéraux ou d’entreprise et de donateur·rices individuel·les, qu’elles et ils soient de votre pays ou de l’étranger. Il exclut les ressources que les groupes, organisations et/ou mouvements génèrent de manière autonome (ressource en anglais), telles que les cotisations d’adhésion, contributions volontaires du personnel, de membres et/ou de soutiens, les collectes de fonds communautaires, les locations de salles et ventes de services. Les définitions des différents types de financement, ainsi que de courtes descriptions des différents bailleurs de fonds, sont incluses dans l’enquête pour une meilleure compréhension.