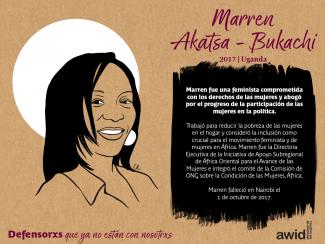

Marren Akatsa-Bukachi

Esta sección de análisis especial ofrece un análisis feminista crítico y acceso a los recursos clave relacionados con la «protección de la familia» en los espacios internacionales de derechos humanos.

Durante los últimos años, venimos observando una nueva y preocupante tendencia en el ámbito internacional de derechos humanos, donde se están empleando discursos sobre la «protección de la familia» para defender violaciones cometidas contra miembros de la familia, de modo de reforzar y justificar la impunidad y para coartar la igualdad de derechos en el seno de la familia y la vida familiar.

La campaña para «proteger a la familia» es impulsada por proyectos conservadores que tienen como fin imponer interpretaciones «tradicionales» y patriarcales de familia; quitando los derechos de las manos de sus miembros para ponerlos en las de la institución «familia».

Desde 2014 un grupo de estados opera como bloque en espacios de derechos humanos, bajo el nombre «Group of Friends of the Family» [Grupo de amigos de la familia], y a partir de entonces se han aprobado resoluciones sobre la «Protección de la familia» todos los años.

Esta agenda se ha extendido más allá del Consejo de Derechos Humanos (HRC, por sus siglas en inglés). Hemos visto cómo el lenguaje regresivo sobre «la familia» se ha introducido en la Comisión de la Condición Jurídica y Social de las Mujeres (CSW, por sus siglas en inglés), y hemos asistido a intentos por incluir este lenguaje en las negociaciones sobre los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible.

AWID trabaja con asociadxs y aliadxs para resistir conjuntamente las agendas regresivas de «Protección de la familia» y otras, y para defender la universalidad de los derechos humanos.

En respuesta a la creciente influencia de actores regresivos en los espacios de derechos humanos, AWID se ha unido con aliadxs para formar el Observatorio de la Universalidad de los Derechos (OURs, por sus siglas en inglés). OURs es un proyecto colaborativo que monitorea, analiza y comparte información sobre iniciativas anti-derechos tales como la «Protección de la familia».

Derechos en Riesgo, el primer informe de OURs, traza un mapa de los actores que conforman el cabildeo global anti-derechos e identifica sus discursos y estrategias principales, señalando los efectos que estos discursos y estrategias están teniendo sobre nuestros derechos humanos.

El informe expone a la «Protección de la familia» como una agenda que ha promovido la colaboración entre una amplia gama de actores regresivos en las Naciones Unidas. La describe como un marco estratégico que aloja «múltiples posiciones patriarcales y anti-derechos, cuyo marco, a su vez, apunta a justificar e institucionalizar estas posiciones».

La organización comunitaria de mujeres negras en la región del Norte del Cauca en Colombia se remonta al pasado colonial del país, que está marcado por el racismo, el patriarcado y el capitalismo que sustentaron la esclavitud como un medio para explotar los ricos suelos de la región.

Estas organizadoras son las heroínas de un amplio movimiento por la autonomía negra, que lucha por el uso sostenible de los bosques y los recursos naturales de la región como elementos vitales para su cultura y sustento.

Durante 25 años, la Asociación de Mujeres Afrodescendientes del Norte del Cauca (ASOM) se ha dedicado a impulsar la organización de mujeres afrocolombianas en el Norte del Cauca. Se establecieron en 1997 como respuesta a las continuas violaciones de derechos humanos, la ausencia de políticas públicas, el manejo inadecuado de los recursos naturales y la falta de oportunidades para las mujeres en el territorio.

Han forjado la lucha para asegurar los derechos étnico-territoriales, para poner fin a la violencia contra las mujeres y obtener el reconocimiento del papel de las mujeres en la construcción de la paz en Colombia.

Tenue des autres sessions de rédaction du document final d’Addis-Abeba

Pour plus d’informations, voir le « guide du routard des OSC » (le CSO Hitchhiker’s Guide – en anglais).

Pour revendiquer votre pouvoir en tant qu’experte sur la situation du financement des mouvements féministes.

(« main échangée »)

Terme des communautés noires du Cauca du Nord pour la minga, le travail collaboratif dans les fermes, basé sur l'entraide et la solidarité.

.

The 14th Forum theme is “Feminist Realities: our power in action”.

We understand Feminist Realities as the different ways of existing and being that show us what is possible, despite dominant power systems, and in defiance and resistance to them. We understand these feminist realities as reclamations and embodiments of hope and power, and as multi-dimentional, dynamic and rooted in specific contexts and historical moments.

Read more about Feminist Realities

La dotación de recursos de los movimientos feministas es fundamental para garantizar una presencia más justa y pacífica y un futuro en libertad. En las últimas décadas, los donantes comprometieron una cantidad más considerable de dinero para la igualdad de género; sin embargo, apenas el 1% del financiamiento filantrópico y para el desarrollo se ha destinado real y directamente a dotar de recursos al cambio social encabezado por los feminismos.

La dotación de recursos de los movimientos feministas es fundamental para garantizar una presencia más justa y pacífica y un futuro en libertad. En las últimas décadas, los donantes comprometieron una cantidad más considerable de dinero para la igualdad de género; sin embargo, apenas el 1% del financiamiento filantrópico y para el desarrollo se ha destinado real y directamente a dotar de recursos al cambio social encabezado por los feminismos.

Para luchar por la abundancia y acabar con esta escasez crónica, la encuesta ¿Dónde está el dinero? es una invitación a lxs promotorxs feministas y por la justicia de género a sumarse al proceso de la construcción colectiva de razones fundadas y evidencias para movilizar más y mejores fondos y recobrar el poder en el ecosistema de financiamiento de hoy. En solidaridad con los movimientos que continúan invisibilizados, marginados y sin acceso a financiamiento básico, a largo plazo, flexible y fiduciario, la encuesta ¿Dónde está el dinero? pone de relieve el estado real de la dotación de recursos, impugna las falsas soluciones y señala cómo los modelos de financiamiento necesitan modificarse para que los movimientos prosperen y puedan hacer frente a los complejos desafíos de nuestro tiempo.

|

383 people |

We have always worked towards ensuring that our Forums are co-developed with partners, movements and our priority constituencies.

For our upcoming Forum, we aim to deepen and strengthen that spirit and practice of co-creation and collaboration. We also recognize the need to improve the balance between the inclusion of many voices and experiences with room for participants and staff to breathe, take pause and enjoy some downtime.

This Forum will be different in the following ways:

Identify and demonstrate opportunities to shift more and better funding for feminist organizing, expose false solutions and disrupt trends that make funding miss and/or move against gender justice and intersectional feminist agendas.

The Cover

|

The Powerful

|

The Ivy

|

The Howl

|

Production and entrepreneurship |

Artisana

|

Please visit the "Funding ideas" page to get some ideas and inspiration for how you can fund your participation at the next Forum, including the limited support AWID will be able to provide.