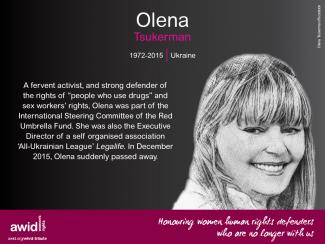

Olena Tsukerman

The Human Rights Council (HRC) is the key intergovernmental body within the United Nations system responsible for the promotion and protection of all human rights around the globe. It holds three regular sessions a year: in March, June and September. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) is the secretariat for the HRC.

Debating and passing resolutions on global human rights issues and human rights situations in particular countries

Examining complaints from victims of human rights violations or activist organizations on behalf of victims of human rights violations

Appointing independent experts (known as “Special Procedures”) to review human rights violations in specific countries and examine and further global human rights issues

Engaging in discussions with experts and governments on human rights issues

Assessing the human rights records of all UN Member States every four and a half years through the Universal Periodic Review

AWID works with feminist, progressive and human rights partners to share key knowledge, convene civil society dialogues and events, and influence negotiations and outcomes of the session.

Ȃurea Mouzinho is a feminist economic justice organizer from Luanda, Angola, with a 10-year career in research, grant-making, advocacy, and movement-building for women's rights and economic justice across Africa and the global south. Currently the Program Manager for Africa at Thousand Currents, she also serves on the Feminist Africa Editorial Board and is a member of Ondjango Feminista, a feminist collective she co-founded in 2016. A new mom to a Gemini boy, urea enjoys slow days with her young family and taking long strolls by the beach.

She occasionally tweets at @kitondowe.

"¿Dónde está el dinero para las organizaciones feministas?

¿Cuánto sabes sobre la movilización de recursos feminista? Responde el cuestionario de AWID “¿Dónde está el dinero para las organizaciones feministas?” y pon a prueba tus conocimientos

Responde el cuestionario en línea Descárgalo e imprímelo.

Simone a 20 ans d’expérience dans le soutien à la gestion et l’administration dans des organisations à but non lucratif, en particulier dans l’enseignement médical post universitaire et la formation aux Technologies de l'Information et de la Communication. Elle possède des qualifications en soutien à la gestion et en études parajuridiques. Elle est basée en Afrique du Sud, aime voyager et agit en tant que généalogiste amatrice.

Ce rapport révèle la réalité du financement des organisations féministes et de défense des droits des femmes dans un contexte de bouleversements politiques et financiers. S’appuyant sur plus de dix ans d’analyse depuis la dernière étude Où est l’argent ? de l’AWID (Arroser les feuilles, affamer les racines), il dresse un bilan des progrès réalisés, des lacunes persistantes et des menaces croissantes dans le domaine du financement féministe.

Le rapport salue le pouvoir des initiatives menées par les mouvements pour façonner le financement selon leurs propres conditions, tout en alertant sur les coupes massives dans l’aide au développement, le recul de la philanthropie et l’escalade des offensives anti-droits.

Il appelle les bailleurs de fonds à investir massivement dans l’organisation féministe, infrastructure essentielle pour la justice et la libération, et invite les mouvements à réimaginer des modèles de financement audacieux et autodéterminés, fondés sur le soin, la solidarité et le pouvoir collectif.

Bien plus de la moitié de la population mondiale est aujourd’hui dirigée par l’extrême droite. C’est sur cette toile de fond que défenseur·e·s des droits humains et féministes luttent pour « tenir bon », protéger le multilatéralisme et le système international des droits humains, alors que leurs engagements les exposent à de violentes répressions. Ces institutions sont cependant de plus en plus soumises aux intérêts du secteur privé. Les grandes entreprises, surtout les sociétés transnationales, siègent à la table des négociations et occupent des fonctions de leadership dans plusieurs institutions multilatérales, l’ONU notamment. Le lien entre ultranationalisme, restriction de l’espace civique et emprise des entreprises a un impact considérable sur la réalisation ou non des droits humains pour tout le monde.

Nana is a feminist organizer and a reproductive rights and population policy researcher based in Egypt. She is a member of Realizing Sexual and Reproductive Justice (RESURJ), a member of the Advisory Board of the A Project in Lebanon, and a member of the Community Committee of Mama Cash. Nana holds an MSc in Public Health from KIT Institute and Vrije University in Amsterdam. In her work, she follows and contextualizes national population policies while building evidence that addresses modern eugenics, regressive international aid, and authoritarianism. Previously, she was part of the Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research, the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, and Ikhtyar Feminist Collective in Cairo.

Only 18% of trans and travesti people in Argentina have access to formal work.

Le sommet climat organisé par et pour les mouvements.

📅 12 novembre - 16 novembre 2025

📍 Université fédérale du Pará, Belém

Site web en anglais

A magical experience of feminist story telling led by pan-African feminist Coumba Toure, performing in the age old tradition of West African griots.

And we gathered again

We gathered our stories our strength

our songs

our tears

our rage

our dreams

our success

our failures

And we pull them all together

In one big bowl to share

for a moon of thoughts

And we stay in touch

We shake each others minds

we caress each other souls

While our hands still are tied

And our kisses and hugs are banned

Yet we grow stronger by the hour

Weaving together our voices

Crossing the sound barriers

as we speak in tongues

We are getting louder and louder

We know about differences from others

and from each other so we are stitching our beauties into patchwork or thoughts

From our deepest learnings from our powers

Sometimes we are surrounded by terror

by confusions by dishonesty

But we wash out in the Ocean of love

We are weavers of dreams

To clothes or new world

Thread after thread

As small as we are

Like little ants building our movement

Llike little drops building our rivers

We take steps forward and steps backward

Dancing our way back to sanity

Sustain to the rhythm of our hearts keep

Beating please don't not stop

And we are here transmitter of forgotten generosity

drop after drop growing like the ocean

growing like the river flowing from our souls .

showing our strength to be the water

that will clean this world

and we are gathering again can you feel us

I would lie if I say I said I am

Ok not to see you I do miss my people

I miss your touch and

You unfiltered and unrecorded voices

I miss our whispers and our screams

Our cries of the aborted revolution

We only want to give birth to new worlds

So fight to erase the borders between us

And we gathered again

We gathered our stories our strength

our songs

our tears

our rage

our dreams

our success

our failures

And we pull them all together In one big bowl to share

For a moon of thoughts

And we stay in touch

We shake each others minds

we caress each other souls

While our hands still are tied

And our kisses and hugs are banned

Yet we grow stronger by the hour

Weaving together our voices

Crossing the sound barriers

as we speak in tongues

We are getting louder and louder

We know about differences from others

and from each other so we are stitching our beauties into patchwork or thoughts

From our deepest learnings from our powers Sometimes we are surrounded by terror by Confusions by dishonesty

But we watch out in the Ocean of love

We are weavers of dreams

To clothes or new world

Thread after thread

As small as we are like little ants building our movements

like little drops building our rivers We take steps forward and steps backward

dancing our way back to sanity

Sustain to the rhythm of our hearts

keep beating please don't not stop

And we are here transmitter of forgotten generosity

Drop after drop growing like the ocean

growing like the river flowing from our souls

showing our strength to be the water

that will clean this world

and we are gathering again can you feel us

I would lie if I I said I am Ok

not to see you

I do miss my people

I miss your touch and

You unfiltered and unrecorded voices

I miss our whispers and our screams

Our cries over the aborted revolutions

We only want to give birth to new worlds

So fight to erase the borders between us

Please don’’t stop

AWID began in 1982 and has grown and transformed since then into a truly global organization.

Read From WID to GAD to Women's Rights: The First 20 Years of AWID

As world leaders gather in Brazil, it’s vital that feminist movements especially from the Global Majority have autonomous spaces to gather, strategize, and disrupt.

These Hubs challenge the elitism of climate talks, center lived experiences, and aim to build collective power across borders. They offer a critical counterbalance to top-down, often exclusionary international negotiations. The Hubs aim to foster community-driven solutions, amplify feminist demands, and ensure that feminist principles of care and solidarity shape the climate agenda. It’s not just about being present at COP30, it’s about reshaping the conversation on climate justice on feminist terms.

ترجمة مارينا سمير

|

أكوسوا هانسون، فنانة وناشطة مقيمة في أكرا في غانا. تشمل أعمالها على ميادين الإذاعة والتلفزيون ووسائل الإعلام المطبوعة والمسرح والأفلام ومعارض القصص المصورة والأعمال الفنية ثُلاثية الأبعاد والروايات المصورة. تتمحور نشاطية أكوسوا حول قضايا الوحدة الأفريقية والنسوية، مع اهتمام خاص بتقاطع الفن مع الثقافة الشعبية والنشاطية. حائزة على ماجستير في الفلسفة في الدراسات الأفريقية، مع التركيز على الدراسات الجندرية والفكر الفلسفي الأفريقي. أكوسوا مبتكرة مود جيرلز، وهي سلسلة روايات مصورة، تتابع مغامرات أربعة أبطال خارقين يقاتلون من أجل إفريقيا خالية من الفساد والاستعمار الجديد والأصولية الدينية، وثقافة الاغتصاب ورهاب المثلية الجنسية وغير ذلك. تعمل كمذيعة في Y 107.9 FM، غانا. |

في هذه الرسومات، تنخرط فتاة القمر وادجيت في ممارسة حميمية مع شيطان ثنائي الجندر. من بين فتيات القمر الأربعة، وادجيت هي المُعالِجة والفيلسوفة ووسيطة العرّافة. هي تقوم بذلك من أجل إطلاق عملية علمية وروحية، تُطلِق عليها تسمية «الاستنارة بضوء البدر». خلال هذه العملية، تشكّل تسلسلاً زمنياً حيّاً بين ذكرياتها وحواسها ومشاعرها ورؤاها وخيالاتها. إنّها أحد أشكال السفر عبر الزمن من خلال الذبذبات، من أجل اكتشاف ما تُسميه «تجلّيات الحقيقة». أثناء التجربة، تتضمّن إحدى رؤى وادجيت الضبابية اقتراب نهاية العالم نتيجة تدمير الناس للبيئة في خدمة الرأسمالية الشرهة؛ وذكرى طفولة حول دخول المستشفى بعد التشخيص بمرض نفسي؛ ورؤية لأصل قصّة فتيات القمر يظهر فيها الرمز التوراتي نوح، كفتاة قمر سوداء من عصر قديم تحذّر من أخطار التلوث البيئي.

تمتدّ ممارسات الـ»بي دي إس إم» إلى أبعد من كونها كينك مرح يقود لاستكشافات حسّية، فبإمكانها أن تكون طريقة للتعامل مع الألم العاطفي والصدمات. لقد كانت وسيلةً للتعافي الجنسي بالنسبة لي، بتقديمها نمط للتحرّر الجذري. تطهيرٌ ما، يحدث، عند وقوع ألمٍ مادّي على الجسد. يقع هذا الألم في وجود تراضٍ، فيستخرج ألمًا عاطفيًا، كما لو كان «يستدعيه». نزول السوط على جسدي يسمح لي بتحرير مشاعر مكبوتة: توتّر، اكتئاب، شعوري بغياب دفاعاتي في وجه ضغوطاتٍ تُغرقني أحيانًا. عند الانخراط في الـ»بي دي إس إم» كسبيل للتعافي، على العشّاق أن يتعلّموا كيف يكونون شديدي الوعي ببعضهم البعض، ومسؤولين عن بعضهم البعض. فحتى لو كانت الموافقة قد أُعطيت في البداية، علينا أن نكون منتبهين لأيّ تغيّرات قد تطرأ أثناء الممارسة، خاصةً مع احتدام المشاعر. أتعامل مع الـ»بي دي إس إم» بفهمٍ لأنه ينبغي أن يكون الحبّ والتعاطف أساسًا لعملية الاستسلام للألم، وبذلك أخلق مساحة أو أنفتح للحبّ.

إن الاهتمام برعاية ما بعد وقوع الألم يُعَدّ استكمالًا للعملية. يمكن لذلك أن يحدث بطُرُقٍ بسيطة جدًا مثل الاحتضان، التأكّد ممّا إذا كان الآخر يرغب في شرب الماء، مشاهدة فيلمٍ معًا، مشاركة عناق أو حتى مشاركة سيجارة حشيش. يمكن لهذه الرعاية أن تمتثل لأيّ ما كانت عليه لغة حبّك المُختارة. مع إدراك أنّ جروحًا قد فُتِحَت، تُعَدّ هذه المساحة من الاحتواء ضرورية من أجل استكمال عملية التعافي. إنّه أكبر درسٍ في ممارسة التعاطف وتعلّم كيف تحتوي شريكك/ شريكتك حقًا، نظرًا لحساسية تمييع الحدود الفاصلة بين الألم والمتعة. بهذه الطريقة، يصبح الـ»بي دي إس إم» أحد أشكال أعمال الرعاية بالنسبة لي.

بعد ممارسة جنسية فيها ممارسات «بي دي إس إم»، أشعر بصفاء ذهني وهدوء يَضَعاني في مساحة إبداعية عظيمة ويمكّناني روحيًا. مشاهدة الألم يتحوّل آنيّاً لشيء آخر هي أشبه بتجربة سحرية. وبالمثل، تجربة الـ»بي دي إس إم» المحرِّرة على المستوى الشخصي تسمح لوادجيت بالوصول إلى المعرفة المُسبَقة والحكمة والصفاء الذهني مما يساعدها في واجباتها كفتاة قمر في مواجهة الأبوية الأفريقية.

وُلِدَت «فتيات القمر» أثناء عملي كمديرة لـ»دراما كوينز»، وهي منظمة فنّية شبابية ناشطة في غانا. منذ تأسيسنا في 2016، استخدمنا وسائط فنّية مختلفة كجزءٍ من عملنا الناشطي النسوي والبيئي والعموم- أفريقي. استخدمنا الشِعر والقصص القصيرة والمسرح والأفلام والموسيقى لمناقشة قضايا مثل الفساد والأبوية والتدهور البيئي ورهاب المثلية الجنسية. ناقَشَت أعمالنا المسرحية الافتتاحية مثل «خَيّاطة شارع سان فرانسيس» و»حتى يفيق أحدهم» مشكلة ثقافة الاغتصاب في مجتمعاتنا. كما يُزعم أن «مثلنا تمامًا» كانت من أوائل الانتاجات المسرحية في غانا التي تناقش بشكل مباشر قضية رهاب المثلية الجنسية المتغلغلة في البلد. كما ساهمت «جامعات غانا الكويرية»، وهي ورشة لصناعة الأفلام الكويرية لتدريب صنّاع الأفلام الأفارقة، في تدريب صنّاع أفلام من غانا ونيجيريا وجنوب أفريقيا وأوغاندا. وعُرِضَت الأفلام المصنوعة في الورشة في مهرجانات، مثل فيلم «فتاة رضيعة: قصة شخص بيني الجنس». ولذلك، فإنّ الانتقال إلى وسيط الروايات المصوّرة هو تطوّر طبيعي.

منذ حوالي سبع سنوات، بدأتُ بكتابة رواية لم أكملها أبدًا عن حياة أربع نساء. في عام 2018، فتحت «مبادرة المجتمع المفتوح لغرب إفريقيا» (OSIWA) فرصة مِنحة أطلقت إنتاج المشروع وتحوّلت روايتي غير المكتملة إلى فتيات القمر. هناك جزءان من فتيات القمر، يتكوّن كلّ منهما من ستّة فصول. الكُتّاب والمحرّرون المساهمون في الموسم الأول هم سوهايدا دراماني، وتسيدي كان تاماكلوي، وجورج هانسون، ووانلوف كوبولور. كتّاب الموسم الثاني هم يابا أرما ونادية أهيدجو وأنا. قام الفنان الغاني كيسوا وستوديو «أنيماكس إف واي بي»، وهو ستوديو رسوم متحرّكة وتصميمات وتأثيرات بصرية، بالرسوم التوضيحية للشخصيات وصياغتها مفاهيميًا.

لقد كانت كتابة فتيات القمر، بين 2018 و2022، عملَ حبٍّ بالنسبة لي، بل بالأحرى، عمل من أجل التحرّر. أهدف أن أكون مجدِّدة في الشكل والأسلوب: لقد اهتممت بتحويل أنماطٍ أخرى من الكتابة، مثل القصص القصيرة والشِعر، لتلائم بنية القصص المصوّرة. تستهدف فتيات القمر مناقشة القضايا الكبرى وتكريم النشطاء الموجودين في الحياة الحقيقية، من خلال إدماج الرسومات والنصوص، كما يحدث في القصص المصوّرة عادةً. قراري بمركزة النساء الكوير كبطلات خارقات، وهو أمر نادر الحدوث في هذا النوع من الفن، أصبح له معنى أكبر بكثير عندما بدأ يتطوّر أمر خطير في غانا في عام 2021.

شهد العام الماضي تصاعد في وتيرة العنف ضد مجتمع الميم عين في غانا، والتي بدأت بإغلاق أحد مراكز مجتمع الميم عين. أعقب ذلك اعتقالات تعسفية وسجن أشخاص مشكوك في انتمائهم للطيف الكويري، كذلك أشخاص متّهمين بالدفع بـ»أجندة مثلية». تُوِّج ذلك بتقديم مشروع قانون ضد الميم عين في البرلمان الغاني تحت إسم «حقوق الإنسان الجنسية اللائقة وقِيَم الأسرة الغانية». يُزعم أن هذا المشروع هو أكثر مشاريع القوانين توحشًا ضد الميم عين كان قد صيغ في المنطقة، وقد أتى لاحقًا على محاولات سابقة في بلاد مثل نيجيريا وأوغندا وكينيا.

أتذكّر بمنتهى الوضوح أول مرّة قرأت فيها مسودة مشروع القانون. لقد كانت ليلة جمعة، والتي عادةً ما أستريح أو أحتفل فيها بعد أسبوع عمل طويل. لحسن الحظ، سُرِّبت المسودّة وتمّت مشاركتها معي على مجموعة واتساب. أثناء القراءة، تسلّل إليّ شعور عميق بالخوف والتوجّس مما أفسد ليلة استراحتي.

اقترح المشروع معاقبة أيّة مناصرة للميم عين بالسجن من خمس لعشرة سنوات، وبتغريم وحبس أي شخص يُعرّف نفسه باعتباره مثلي أو مثلية أو عابر أو عابرة جنسيًا أو ينتمي لأية فئات جنسية أو/وجندرية غير نمطية، إلا إذا «تراجع» وقَبِل الخضوع لعلاج تصحيحي. في مسودة مشروع القانون، حتى اللاجنسيين جُرِّموا. انقضّ مشروع القانون على جميع الحرّيات الأساسية: حرّية الفكر وحرّية الوجود وحرّية أن يتمسّك الشخص بحقيقته ويعيش بها. انقضّ مشروع القانون أيضًا على منصّات التواصل الاجتماعي والفنّ. لو مُرِّر هذا المشروع، ستصبح فتيات القمر عملاً أدبياً محظوراً. ما تقدّم به مشروع القانون كان شرًا خالصًا وبعيد المدى، لقد صُدِمت لدرجة الاكتئاب من عمق الكراهية التي صُنِع منها هذا المشروع. أثناء تصفّحي موقع «تويتر» تلك الليلة، وجدتُ انعكاسًا للرعب الذي شعرت به بداخلي. لقد كان هناك بثًا مباشرًا للمشاعر، حيثُ كان يتفاعل الناس فوريًا مع ما يقرأونه: من عدم تصديق إلى رعب إلى خيبة أمل شديدة وشعور بالأسف عندما أدركنا المدى الواسع الذي رغب المشروع في الانقضاض عليه. البعض غرّدوا عن استعدادهم لجمع ما لديهم والرحيل عن البلاد. بعدها، وكعادة الغانيين، تحوّل الأسف والخوف لدعابة. ومن الدعابة أتى الحماس لتصعيد المقاومة.

لذلك، فالعمل مستمرّ. لقد صنعتُ فتيات القمر لتوفير شكلٍ بديلٍ من التعليم، ولتوفير المعرفة حيثُ قمَعَتها أبوية عنيفة، ولخلق مساحة ظهور لمجتمع الميم عين حيثُ تمّ محوه. من الضروري أيضًا أن يحصل الـ»بي دي إس إم» الأفريقي على منصّة لإظهاره حيثُ أنّ الكثير من الـ»بي دي إس إم» المُمثَّل أبيض. إن المتعة الجنسية، سواء من خلال الـ»بي دي إس إم» أو غيره، مثلها مثل أنماط الحبّ اللامغاير جنسيًا، تتخطى العرق والقارّة، فالمتعة الجنسية وتنوّع خبراتها قديمة بقِدَم الزمن.

This journal edition in partnership with Kohl: a Journal for Body and Gender Research, will explore feminist solutions, proposals and realities for transforming our current world, our bodies and our sexualities.

نصدر النسخة هذه من المجلة بالشراكة مع «كحل: مجلة لأبحاث الجسد والجندر»، وسنستكشف عبرها الحلول والاقتراحات وأنواع الواقع النسوية لتغيير عالمنا الحالي وكذلك أجسادنا وجنسانياتنا.