Contenido relacionado

C.R.I.C Consejo Regional Indígena del Cauca: Cauca: Denuncian Nuevo Homicidio de una Defensora de Derechos Humanos

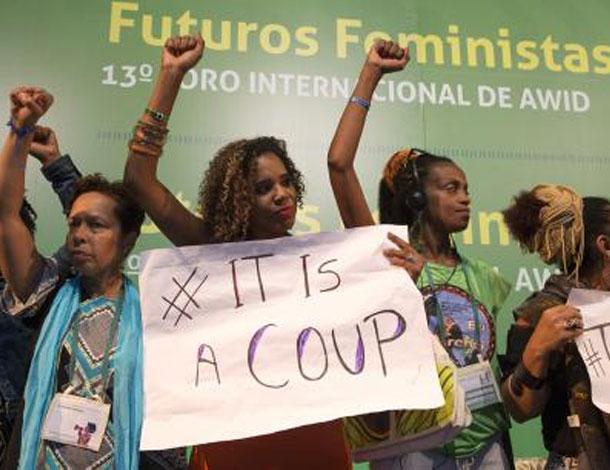

In September 2016, the 13th AWID international Forum brought together in Brazil over 1800 feminists and women’s rights advocates in a spirit of resistance and resilience.

This section highlights the gains, learnings and resources that came out of our rich conversations. We invite you to explore, share and comment!

One of the key takeaways from the 2016 Forum was the need to broaden and deepen our cross-movement work to address rising fascisms, fundamentalisms, corporate greed and climate change.

With this in mind, we have been working with multiple allies to grow these seeds of resistance:

And through our next strategic plan and Forum process, we are committed to keep developing ideas and deepen the learnings ignited at the 2016 Forum.

AWID Forums started in 1983, in Washington DC. Since then, the event has grown to become many things to many peoples: an iterative process of sharpening our analyses, vision and actions; a watershed moment that reinvigorates participants’ feminisms and energizes their organizing; and a political home for women human rights defenders to find sanctuary and solidarity.

Des partenaires mondiaux et régionaux nous ont déjà communiqué certaines idées de rassemblements préalables au Forum, dont nous vous ferons part sous peu.

Si vous projetez d’organiser une réunion avant le Forum, n’hésitez pas à nous le faire savoir !

Plusieurs belles choses ont émergé du Forum des féminismes noires (BFF, selon son acronyme anglais), qui avait été organisé en 2016 par un Groupe consultatif et financé par l’AWID. À l’issue de ce BFF, certaines organisations indépendantes ont ainsi pu voir le jour, telles ques des organisations féministes noires au Brésil. Bien que le BFF n’aura pas lieu cette année, nous nous engageons à partager certains apprentissages clés avec toute personne intéressée à poursuivre le travail d'organisation féministe noire.

Contenido relacionado

C.R.I.C Consejo Regional Indígena del Cauca: Cauca: Denuncian Nuevo Homicidio de una Defensora de Derechos Humanos

Le 14e Forum international de l'AWID aura lieu du 20 au 23 septembre 2021 à Taipei, Taiwan.

Le Forum international de l'AWID est un événement mondial qui offre aux participant·e·s une occasion unique de se rencontrer, tisser des alliances, de faire la fête et d’apprendre des autres dans une ambiance stimulante, riche en émotions et en toute sécurité.

De plus en plus, nous nous efforçons de penser le processus du Forum au-delà des limites de l’événement lui-même. Nous ouvrons des discussions avec des partenaires et renforçons des alliances tout au long de l’année. Nous essayons d’être au plus proches des mouvements locaux pour comprendre leurs difficultés et co-créer des solutions.

Le Forum de l’AWID un espace propice aux discussions en profondeur, qui repousse nos limites internes et externes et favorise le développement personnel et professionnel, en plus de renforcer nos mouvements pour la justice sociale, de genre et les droits des femmes.

Nous envisageons ce moment de rencontre comme une réponse à l’urgence de favoriser un engagement plus marqué et une action mieux concertée entre les organisations féministes, les défenseur·e·s des droits des femmes et les autres activistes de justice sociale. Pour nous, le Forum est plus qu’un événement. Il nourrit nos réflexions respectives et nous aide à cerner des initiatives concrètes dans lesquelles les mouvements féministes et peuvent s’engager avec d’autres acteurs·trices.

Au départ un événement national d’environ 800 personnes, le Forum rassemble aujourd'hui plus de 2 000 féministes, des dirigeant·e·s communautaires, des activistes de justice sociale et des bailleurs de fonds du monde entier.

Compte tenu de la complexité du monde d'aujourd'hui, le Forum de l'AWID 2016 ne s'est pas concentré sur un « problème » particulier mais a plutôt exploré comment créer des moyens efficaces de travailler ensemble !

Malgré le contexte difficile dans lequel s’est déroulé le Forum de 2016 (l’épidémie de Zika, la grève au ministère des Affaires étrangères brésilien, la destitution de la présidente Dilma Rousseff et l’instabilité qui a suivi), il a rassemblé plus de 1800 participant-e-s issu-e-s de 120 pays et territoires de toutes les régions du monde.

Téléchargez le rapport d’évaluation

Le 12e Forum de l’AWID s’est tenu à Istanbul en Turquie en 2012, avec pour thème central Transformer le pouvoir économique pour avancer les droits des femmes et la justice. Ce Forum fut le plus important et le plus diversifié de l’histoire, rassemblant quelque 2 239 activistes pour les droits des femmes en provenance de 141 pays différents. Parmi elles-eux, environs 65 % venaient de pays du Sud, près de 15 % étaient des jeunes femmes de 30 ans et moins, alors que 75 % participaient au Forum pour la première fois.

Le Forum s’est focalisé sur la transformation du pouvoir économique pour faire progresser les droits des femmes et la justice en proposant plus de 170 activités incluant des ateliers de formation en économie féministe, en passant par toute une séries d’ateliers de discussion et autres tables rondes solidaires autour de 10 grandes questions cruciales.

Dans l’élan du Forum, nous avons transformé la page qui lui était dédiée en un outil multimédia en ligne qui intègre également les contenus générés par les participant-e-s sur toutes les composantes du Forum.

Visitez l'archive web du Forum 2012

Nous vivons dans un monde où la destruction de la Nature alimente notre économie mondiale actuelle. |

Même en période de crise climatique, les gouvernements continuent d'encourager les industries agricoles à grande échelle à se développer. Ces activités empoisonnent la terre, menacent la biodiversité et détruisent la production alimentaire et les moyens de subsistance locaux. Pendant ce temps, alors que les femmes produisent la majorité de la nourriture dans le monde, elles ne possèdent presque aucune terre. |

|

Et si nous percevions la terre et la Nature non pas comme une propriété privée à exploiter, mais comme une totalité avec laquelle vivre, apprendre et coexister harmonieusement ? Et si nous réparions nos relations avec la terre et adoptions des alternatives plus durables qui nourrissent à la fois la planète et ses communautés? Nous Sommes la Solution (NSS) est l'un des nombreux mouvements dirigés par des femmes qui s'efforcent d'atteindre cet objectif. Voici leur histoire. |

|

English body

AGROÉCOLOGIE ET SOUVERAINETÉ ALIMENTAIRE EN TANT QUE RÉSISTANCE |

Aujourd'hui, la production alimentaire industrielle à grande échelle utilise des plantations à culture unique, des organismes génétiquement modifiés et d'autres pesticides qui détruisent la terre et les connaissances des communautés locales. |

L'agroécologie est une résistance à l'agriculture hyper-industrialisée qu’utilisent les multinationales. L'agroécologie donne la priorité à l'agriculture à plus petite échelle, aux cultures multiples et à la production alimentaire diversifiée, tout en centrant les connaissances et pratiques traditionnelles locales. L'agroécologie va de pair avec les revendications de souveraineté alimentaire, ou le "droit des peuples à une alimentation saine et culturellement appropriée produite par des méthodes écologiquement rationnelles et durables, et leur droit de définir leurs propres systèmes alimentaires et agricoles" (Via Campesina, Déclaration de Nyéléni).

Le rôle des femmes, des communautés indigènes et rurales et des personnes racialisées des pays du Sud Global est essentiel dans la préservation des systèmes alimentaires.

Les agroécologistes féministes s'efforcent aussi de démanteler les rôles de genre oppressifs et les systèmes patriarcaux intégrés à la production alimentaire. Comme le montrent les héroïnes de Nous Sommes la Solution, elles génèrent une agroécologie libératrice en renforçant la résilience des communautés, en autonomisant les femmes paysannes et agricultrices tout en en préservant les traditions locales, les territoires et les connaissances des communautés productrices de nourriture.

Related content

African Women's Development Fund: Remembering a Warrior: Prudence Mabele

BBC: Prudence Mabele: The life of the South African HIV campaigner

Mail and Guardian: The Pied Piper of the broken-hearted: HIV activist Prudence Mabele

Face2Face Africa: Prudence Mabele, 1st Black SA Woman To Reveal HIV Positive Status Dies At 46

Ms. Prudence Mabele - I'm committed to respond to HIV! (Video)

AWLN Interview with Prudence Mabele of South Africa (Video)

Sangoma: Why I take ARVs (Video)

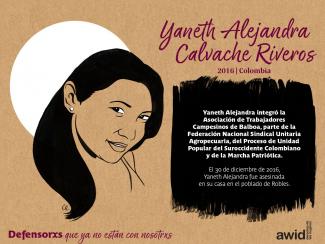

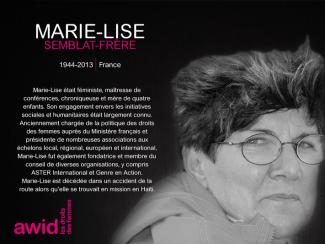

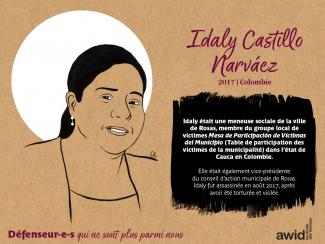

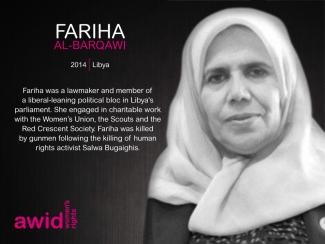

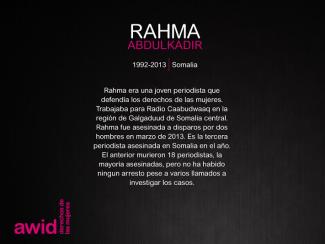

Une étudiante, une scénariste, une leader, une avocate. Les quatre femmes auxquelles nous rendons hommage ci-dessous avait toutes leur propre façon de vivre leur activisme, mais elles avaient en commun la promotion et la défense des droits des personnes lesbiennes, gaies, bisexuelles, trans*, queer et intersexes. Nous vous invitons à vous joindre à nous pour commémorer ces défenseuses, leur travail et l'héritage qu’elles nous ont laissé. Faites circuler ces mèmes auprès de vos collègues et amis ainsi que dans vos réseaux et twittez en utilisant les hashtags #WHRDTribute et #16Jours.

S'il vous plaît cliquez sur chaque image ci-dessous pour voir une version plus grande et pour télécharger comme un fichier

Nous Sommes la Solution uplifts and grows the leadership of rural women working towards African solutions for food sovereignty.

6 Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRDs) across Western and Southeastern Europe have in their lifetime researched, campaigned, participated in and advanced peace and women’s rights movements be it through political and social activism or through dance. We are grateful for the legacy they have left. Please join AWID in honoring these women, their activism and legacy by sharing the memes below with your colleagues, networks and friends and by using the hashtags #WHRDTribute and #16Days.

Please click on each image below to see a larger version and download as a file