Madelaine Parent

Women human rights defenders (WHRDs) worldwide defend their lands, livelihoods and communities from extractive industries and corporate power. They stand against powerful economic and political interests driving land theft, displacement of communities, loss of livelihoods, and environmental degradation.

Extractivism is an economic and political model of development that commodifies nature and prioritizes profit over human rights and the environment. Rooted in colonial history, it reinforces social and economic inequalities locally and globally. Often, Black, rural and Indigenous women are the most affected by extractivism, and are largely excluded from decision-making. Defying these patriarchal and neo-colonial forces, women rise in defense of rights, lands, people and nature.

WHRDs confronting extractive industries experience a range of risks, threats and violations, including criminalization, stigmatization, violence and intimidation. Their stories reveal a strong aspect of gendered and sexualized violence. Perpetrators include state and local authorities, corporations, police, military, paramilitary and private security forces, and at times their own communities.

AWID and the Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition (WHRD-IC) are pleased to announce “Women Human Rights Defenders Confronting Extractivism and Corporate Power”; a cross-regional research project documenting the lived experiences of WHRDs from Asia, Africa and Latin America.

"Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries: an overview of critical risks and Human Rights obligations" is a policy report with a gender perspective. It analyses forms of violations and types of perpetrators, quotes relevant human rights obligations and includes policy recommendations to states, corporations, civil society and donors.

"Weaving resistance through action: Strategies of Women Human Rights Defenders confronting extractive industries" is a practical guide outlining creative and deliberate forms of action, successful tactics and inspiring stories of resistance.

The video “Defending people and planet: Women confronting extractive industries” puts courageous WHRDs from Africa, Asia, and Latin America in the spotlight. They share their struggles for land and life, and speak to the risks and challenges they face in their activism.

Challenging corporate power: Struggles for women’s rights, economic and gender justice is a research paper outlining the impacts of corporate power and offering insights into strategies of resistance.

AWID acknowledges with gratitude the invaluable input of every Woman Human Rights Defender who participated in this project. This project was made possible thanks to your willingness to generously and openly share your experiences and learnings. Your courage, creativity and resilience is an inspiration for us all. Thank you!

Día 1

Come meet the feminist economies we LOVE.

The economy is about how we organize our societies, our homes and workplaces. How do we live together? How do we produce food, organize childcare, provide for our health? The economy is also about how we access and manage resources, how we relate with other people, with ourselves and with nature.

Feminists have been building economic alternatives to exploitative capitalist systems for ages. These alternatives exist in the here and now, and they are the pillars of the just, fairer and more sustainable worlds we need and deserve.

We are excited to share with you a taste of feminist economic alternatives, featuring inspiring collectives from all around the world.

Sessions de consultation complémentaires sur la version préliminaire du document final

(¡con invitades especiales!)

📅Martes 12 de marzo

🕒6:00 p. m. - 9:30 p. m. EST

🏢 Blue Gallery, 222 E 46th St, New York

Entrada solo con confirmación previa

Fuente: Censo de População de Rua, Prefeitura de São Paulo

|

Edificios abandonados/desocupados |

|

||

Personas que viven en la calle |

||||

|

31,000 |

40.000 |

‘A geopolitical Analysis of Financing for Development’ by Regions Refocus 2015 and Third World Network (TWN) with DAWN.

The Zero Draft Language Map, by Regions Refocus

‘Addis Ababa financing conference: Will the means undermine the goals?‘ by RightingFinance

L’enquête s’adresse aux groupes, organisations et mouvements qui travaillent spécifiquement, ou principalement, à la défense des droits des femmes, des personnes LBTQI+ et pour la justice de genre dans tous les contextes, à tous les niveaux, dans toutes les régions. Si c’est un des principaux piliers du travail de votre groupe, collectif, réseau ou tout autre type d’organisation, que votre structure soit déclarée ou non, récemment constituée ou plus ancienne, nous vous invitons à participer à cette enquête.

*Nous ne collectons pas les réponses à titre individuel ou de fonds féministes et pour les femmes à l’heure actuelle.

En savoir plus sur l'enquête :

Consultez la foire aux questions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Les Femmes Maintiennent les Soins | Les Soins Soutiennent la Vie | La Vie Soutient l'Économie | Qui s'Occupe des Femmes ? | Pas Une de Moins1 | Ensemble | Déjeuner du Dimanche

1Nenhuna a menos se traduit littéralement par « pas une femme de moins » ou « ni una menos » en espagnol - un célèbre slogan féministe en Amérique latine qui a émergé en Argentine en réponse à l'augmentation de la violence sexiste.

Como expresión de nuestro compromiso con hacer que todos los aspectos del Foro AWID sean accesibles, aceptaremos propuestas en forma de audio/video cuando se trate de personas/organizaciones/grupos que no puedan enviarlas por escrito. Si decides enviar tu propuesta en formato de audio/video, por favor responde las preguntas en el mismo orden en que aparecen en el Formulario para Presentar Actividades.

Para presentar un archivo de audio/video, por favor escríbenos utilizando nuestro formulario de contacto. Seleccione «propuesta de actividad» como asunto de mensaje.

Pour revendiquer votre pouvoir en tant qu’experte sur la situation du financement des mouvements féministes.

Meet Clemencia Carabalí Rodallega, an extraordinary Afro-Colombian feminist.

She has worked relentlessly for three decades towards the safeguarding of human rights, women’s rights and peace-building in conflict areas on the Pacific Coast of Colombia.

Clemencia has made significant contributions to the fight for truth, reparations and justice for the victims of Colombia’s civil war. She received the National Award for the Defense of Human Rights in 2019, and also participated in the campaign of newly elected Afro-Colombian and long-time friend, vice-president Francia Marquez.

Although Clemencia has faced and continues to face many hardships, including threats and assassination attempts, she continues to fight for the rights of Afro-Colombian women and communities across the country.

El costo de inscripción para el Foro de AWID cubre, para todxs lxs participantes:

La dotación de recursos de los movimientos feministas es fundamental para garantizar una presencia más justa y pacífica y un futuro en libertad. En las últimas décadas, los donantes comprometieron una cantidad más considerable de dinero para la igualdad de género; sin embargo, apenas el 1% del financiamiento filantrópico y para el desarrollo se ha destinado real y directamente a dotar de recursos al cambio social encabezado por los feminismos.

La dotación de recursos de los movimientos feministas es fundamental para garantizar una presencia más justa y pacífica y un futuro en libertad. En las últimas décadas, los donantes comprometieron una cantidad más considerable de dinero para la igualdad de género; sin embargo, apenas el 1% del financiamiento filantrópico y para el desarrollo se ha destinado real y directamente a dotar de recursos al cambio social encabezado por los feminismos.

Para luchar por la abundancia y acabar con esta escasez crónica, la encuesta ¿Dónde está el dinero? es una invitación a lxs promotorxs feministas y por la justicia de género a sumarse al proceso de la construcción colectiva de razones fundadas y evidencias para movilizar más y mejores fondos y recobrar el poder en el ecosistema de financiamiento de hoy. En solidaridad con los movimientos que continúan invisibilizados, marginados y sin acceso a financiamiento básico, a largo plazo, flexible y fiduciario, la encuesta ¿Dónde está el dinero? pone de relieve el estado real de la dotación de recursos, impugna las falsas soluciones y señala cómo los modelos de financiamiento necesitan modificarse para que los movimientos prosperen y puedan hacer frente a los complejos desafíos de nuestro tiempo.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Activistas de Metzineres en acción |

Más que un simple evento, el Foro de AWID es parte de nuestro Viaje de Realidades Feministas, con muchos espacios en los cuales reunirse, en línea o en forma presencial, para compartir, discutir, elaborar estrategias, y crear conjuntamente realidades feministas.

Infórmate sobre el Viaje de Realidades Feministas y sobre todo lo que sucederá en este Viaje antes del Foro. ¡Y mantente sintonizadx para los anuncios post-Foro!

Estamos estudiando opciones para la participación virtual en el Foro, y compartiremos la información cuando sepamos qué podemos ofrecer.

El Foro Internacional de AWID es un verdadero espacio de encuentro mundial que brinda, a quienes participan, la oportunidad de tejer redes, alianzas, de celebrar y aprender en una atmósfera estimulante, emotiva y segura.

Como proceso, el Foro abarca mucho más que el momento en que nos reunimos. Durante todo el año estamos trabajando con organizaciones y grupos, profundizando nuestras relaciones con ellas, vinculándonos con movimientos locales para entender mejor sus problemas y crear soluciones juntxs.

Como evento, el Foro tiene lugar cada tres o cuatro años en una región diferente del mundo y cristaliza todas las alianzas que hemos venido construyendo como parte de nuestro trabajo.

El Foro de AWID disuelve nuestros límites internos y externos, alberga discusiones en profundidad, colabora con el crecimiento personal y profesional, y fortalece a los movimientos por los derechos de las mujeres y la justicia de género.

El Foro responde a la urgencia de promover una participación y acción más sólidas y coordinadas por parte de lxs feministas, defensorxs de los derechos de las mujeres y de la justicia social, sus organizaciones y movimientos. También creemos que el Foro es más que un evento, ya que puede facilitar procesos que influyen en las ideas y las agendas de los movimientos feministas y de otros actores con quienes nos vinculamos.

El Foro pasó de ser una conferencia nacional con 800 participantes a un encuentro que reúne alrededor de 2000 feministas, líderes comunitarixs, activistas por la justicia social y agencias de financiamiento de todo el mundo.

Dado el complejo mundo que enfrentamos hoy, el Foro de AWID 2016 no se centró en un ‘tema’ en particular, sino en la creación de formas más efectivas de trabajar juntxs.

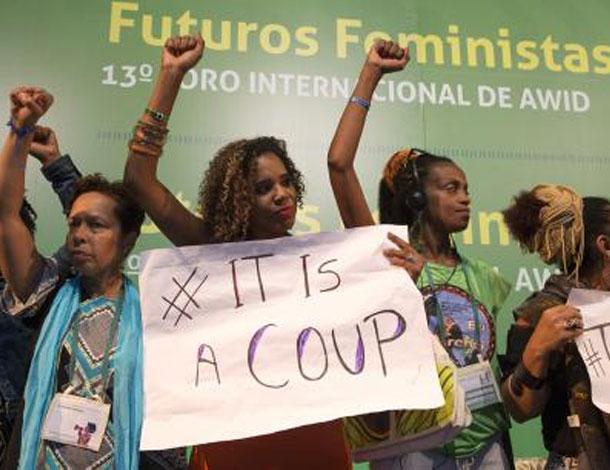

Pese a las dificultades del contexto en el que se celebró este Foro (la epidemia del virus del Zika, una huelga de lxs trabajadorxs del servicio exterior brasileño, el juicio político a la presidenta Dilma Rousseff y la crisis que le siguió), se logró congregar a más de 1800 participantes de 120 países y territorios de todas las regiones del mundo.

Para el 96% de lxs participantes que respondieron a la encuesta de evaluación posterior al Foro, el evento fue una importante fuente de inspiración y energía.

El 98% de lxs participantes lo consideraron un importante espacio de convocatoria para los movimientos feministas, y manifestaron su esperanza de que AWID continúe organizado estos foros.

El 59% de quienes respondieron a la encuesta de evaluación del Foro declaró estar muy satisfechx con el Foro y el 34% algo satisfechx.

Se realizaron más de 150 sesiones en distintos formatos sobre diversos temas, desde la integridad y la libertad corporal, pasando por la violencia de género en el ámbito laboral, hasta estrategias de construcción de poder colectivo.

El primer Foro de Feminismos Negros, se celebró justo antes del Foro de AWID, y reunió a 250 feministas negrxs de todo el mundo, para crear colectivamente un espacio de poder desde donde construir y fortalecer las conexiones intergeneracionales y transnacionales.

Descargar el informe de evaluación del foro

El 12° Foro de AWID se llevó a cabo en el año 2012 en Estambul, Turquía, bajo el título “Transformando el Poder Económico para Avanzar los Derechos de las Mujeres y la Justicia”. El Foro 2012 fue el más grande y diverso que hemos organizado hasta la fecha, con la participación de 2239 activistas por los derechos de las mujeres, de 141 países. El 65% provenía del sur global y casi el 15% eran mujeres jóvenes menores de 30 años, mientras que el 75% de las personas asistían a un Foro de AWID por primera vez.

El programa del Foro se enfocó en la transformación del poder económico para promover los derechos de las mujeres y la justicia. Se ofrecieron más de 170 sesiones de lo más diversas, incluyendo las sesiones de la caja de herramientas económicas feministas para forjar habilidades, sesiones interactivas que representaron los 10 temas del Foro, discusiones en profundidad y las mesas redondas de solidaridad.

Aprovechando el impulso del Foro, hemos transformado la página web en un centro de recursos y aprendizaje que se basa en el contenido generado por las participantes mediante recursos multimedia sobre todos los componentes del Foro.

Visita el archivo web del Foro 2012