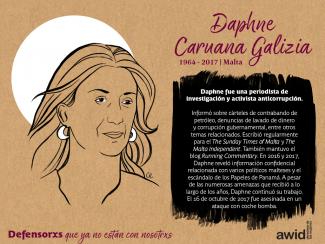

Daphne Caruana Galizia

El Consejo de Derechos Humanos (CDH) es el cuerpo intergubernamental del sistema de las Naciones Unidas responsable de la promoción y protección de todos los derechos humanos en todo el mundo. El HRC se reúne en sesión ordinaria tres veces al año, en marzo, junio y septiembre. La La Oficina del Alto Comisionado para los Derechos Humanos (ACNUDH) es la secretaría del Consejo de Derechos Humanos.

Debate y aprueba resoluciones sobre cuestiones mundiales de derechos humanos y el estado de los derechos humanos en determinados países

Examina las denuncias de víctimas de violaciones a los derechos humanos o las de organizaciones activistas, quienes interponen estas denuncias representando a lxs víctimas.

Nombra a expertos independientes que ejecutarán los «Procedimientos Especiales» revisando y presentado informes sobre las violaciones a los derechos humanos desde una perspectiva temática o en relación a un país específico

Participa en discusiones con expertos y gobiernos respecto a cuestiones de derechos humanos.

A través del Examen Periódico Universal, cada cuatro años y medio, se evalúan los expedientes de derechos humanos de todos los Estados Miembro de las Naciones Unidas

Se está llevarando a cabo en Ginebra, Suiza del 30 de junio al 17 de julio de 2020.

AWID trabaja con socios feministas, progresistas y de derechos humanos para compartir conocimientos clave, convocar diálogos y eventos de la sociedad civil, e influir en las negociaciones y los resultados de la sesión.

COZINHA OCUPAÇÃO 9 DE JULHO

Pour collecter des données probantes qui sont centrées sur les réalités des féministes sur la manière dont l’argent est transféré et qui il atteint réellement.

Es un centro comunitario, donde unx puede tomar cursos y capacitarse en actividades creativas que generan ingresos como peluquería local, cocina y creación artística. Lxs niñxs también pueden disfrutar de actividades culturales y educativas.

El MSTC no trabaja solo. Colabora con instituciones y colectivos de arte para producir experiencias culturales, deportivas y educativas, junto con el acceso crítico a la atención médica. Desde su inicio, este proyecto participativo ha sido liderado y llevado a cabo principalmente por mujeres, bajo el liderazgo de la activista afro-brasileña Carmen Silva, quien alguna vez fue una persona sin hogar.

On July 11, 2024, we had an amazing conversation with great feminists on the state of the funding ecosystem and the power of "Where is the Money?" research.

Special thanks to Cindy Clark (Thousand Currents), Sachini Perera (RESURJ), Vanessa Thomas (Black Feminist Fund), Lisa Mossberg (SIDA), and Althea Anderson (Hewlett Foundation).

L'organisation communautaire des femmes noires dans le Cauca du Nord en Colombie remonte au passé colonial du pays, marqué par le racisme, le patriarcat et le capitalisme qui ont soutenu l'esclavage comme moyen d'exploiter les riches sols de la région. Ces organisatrices sont les héroïnes d'un vaste mouvement pour l'autonomie des personnes noires, luttant pour la gestion durable des forêts et des ressources naturelles de la région, vitales pour leur culture et leur subsistance.

Depuis 25 ans, la Asociación de Mujeres Afrodescendientes del Norte del Cauca (l’Association des Femmes Afro-Descendantes du Cauca du Nord, ASOM) se consacre à la promotion de l'organisation des femmes afro-colombiennes du Cauca du Nord.

L’association a été créée en 1997 en réponse aux violations continues des droits humains, à l'absence de politiques publiques, à la gestion inadéquate des ressources naturelles et au manque d'opportunités pour les femmes dans le territoire.

Elles ont forgé la lutte pour garantir les droits ethno-territoriaux, pour mettre fin aux violences contre les femmes et pour faire reconnaître le rôle des femmes dans la construction de la paix en Colombie.

Click here to watch a video tutorial to support you in filling in the survey.

Contenido relacionado

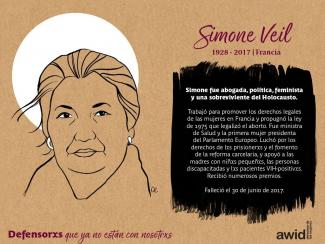

Huffington Post: Muere Simone Veil, la moral de Francia hecha mujer

El Mundo: Muere Simone Veil, superviviente del Holocauso e icono de los derechos de la mujer

Metzineres

No, we appreciate your work but are not asking for responses from individuals at this time.

|

383 personas. |

La encuesta está disponible en KOBO, una plataforma de fuente abierta para recopilar, gestionar y visualizar datos. Para participar, simplemente haz clic en el enlace a la encuesta aquí. Sigue las instrucciones para responder la encuesta.

The in-focus section features the pressing issues affecting women, girls and transgender people around the world, and shines a spotlight on the critical work being carried out by women's rights movements.

AWID and Mama Cash are advisory partners who offer ideas to the Guardian editorial team and help link the Guardian team with diverse women’s rights advocates, organizations and movements around the world.

With the Guardian’s global reach of over 82 million unique browsers a month and its position of influence with policy makers, AWID and Mama Cash see this partnership as an important opportunity to:

If you would like to share suggestions for women’s rights issues, strategies, process or events that you would like to see covered by the in-focus section, you can pitch your ideas here. All suggestions collected through this online form will be shared directly with the Guardian editorial team.The Guardian is solely responsible for all journalistic output and all editorial content is strictly independent.

If you have questions about this project, email: contact@awid.org and/or hello@mamacash.org.